Entering 2014, it was clear that Democrats were in for a tough year. The incumbent president's party almost always sustains losses in the president's sixth year, and President Obama's underwater approval ratings, combined with a Senate map that favored Republicans, left Democrats little hope of defying the odds.

Sure enough, Republicans scored big victories on Election Day, although the scale of those victories and the context in which they occurred proved something of a surprise. From the narratives that dominated the campaign (or didn't) to some of the most surprising results, here are five political developments that threw us for a loop this year.

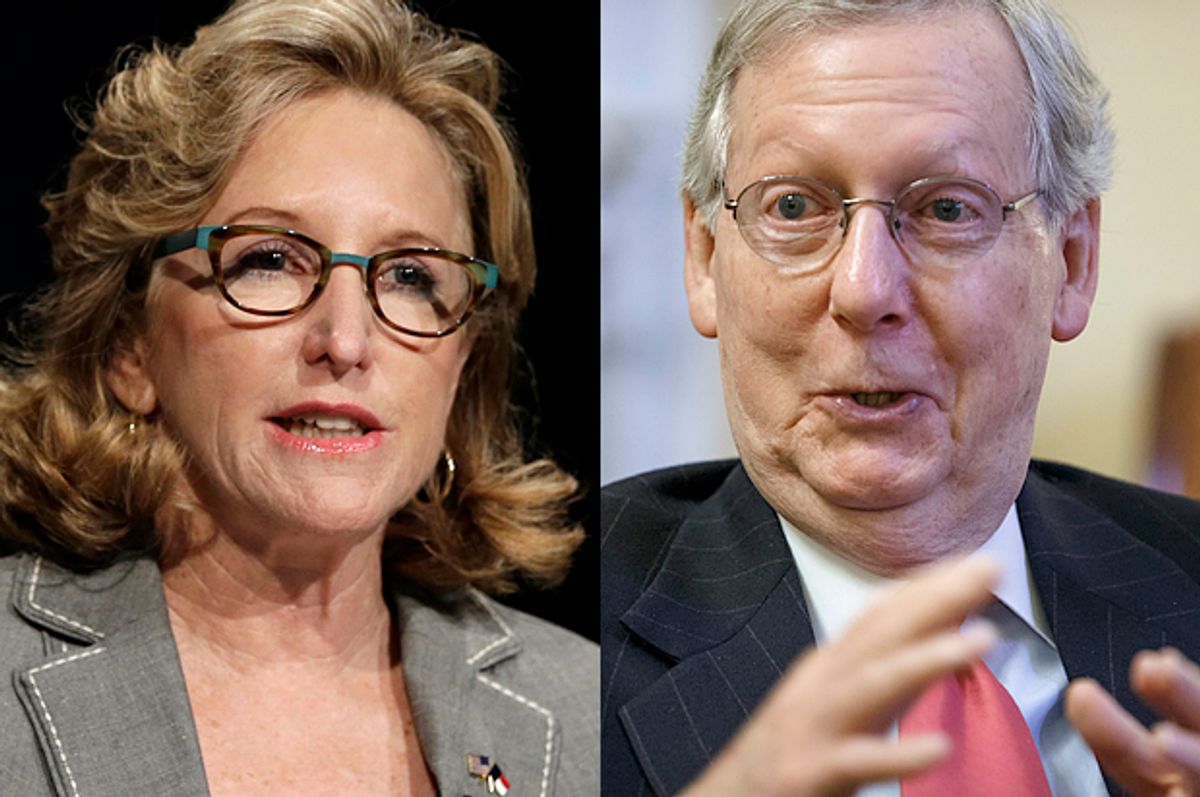

Mitch McConnell's landslide victory

As he geared up to seek a sixth Senate term, Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell confronted a major problem: Voters simply didn't like the Senate minority leader. In late 2012, Public Policy Polling found that McConnell was the most unpopular senator in the country, and as 2014 approached, he wasn't even guaranteed renomination by the Republican Party. Fortunately for McConnell, businessman Matt Bevin's Tea Party primary challenge fizzled, but in Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes, McConnell faced a formidable Democratic opponent.

Early polls showed the candidates locked in a dead heat, with McConnell consistently polling below 50 percent -- often a perilous position for an incumbent. But the national climate and Obama's unpopularity in Kentucky propelled McConnell to a modest lead by the late summer, and he entered Election Day leading in most surveys by the mid-to-high-single digits. Grimes looked unlikely to muster more than the 47 percent of the vote won by Bruce Lunsford, McConnell's Democratic challenger in 2008.

But Grimes didn't just fail to outperform Lunsford -- she barely received 40 percent, losing to McConnell in a 16-point rout. While she faced political headwinds and a deeply entrenched incumbent, her shockingly poor performance also reflects the disastrous campaign she ran. It's difficult to run a successful campaign in a permanent defensive crouch, and Grimes did herself no favors by refusing to say whether she voted for President Obama and promoting the GOP-inspired meme that Obama is waging a "war on coal."

Though it was obvious by the late stages of the campaign that McConnell would win, the margin by which Grimes lost could have consequences beyond 2014. Had Grimes lost by about five points or so, she'd still have been well-positioned to mount another campaign for higher office -- perhaps for Kentucky governor in 2015, against Rand Paul in 2016, or for McConnell's seat in 2020. But a double-digit loss to a deeply unpopular senator isn't typically a prelude to a flourishing political career.

Kay Hagan's loss in North Carolina

Even though Democrats knew they were in for a mostly miserable Election Day, the Tar Heel State was supposed to be a rare bright spot for the party. Sen. Kay Hagan, who vanquished a political titan in 2008 when she ousted Sen. Elizabeth Dole, withstood a fusillade of outside attack ads and had the good fortune of drawing a seriously flawed opponent this year. As speaker of the state House, GOPer Thom Tillis was the face of a controversial, right-wing state legislature, and Hagan pointedly -- almost gleefully -- referred to her opponent as "Speaker Tillis" at every opportunity.

The senator never dominated in the polls, but for the last few months of the race, she led by a small but consistent margin. While I wrote late in the campaign that the smallness of Hagan's lead was a bit nerve-wracking -- particularly given that many conservative supporters of Libertarian candidate Sean Haugh would likely come home to Tillis -- I chalked my worries up to my perpetual political pessimism, and found solace in all the accounts of how Hagan had run what was widely accepted as one of the most brilliant campaigns in the country.

But in an Election Night heartbreaker, Hagan went down to Tillis by 1.7 points -- the smallest margin of defeat among the five incumbent Democrats who lost re-election. Hagan successfully turned out African-American voters, a core Democratic constituency in North Carolina, but the dropoff in turnout among young voters proved fatal; as the New York Times' Nate Cohn notes, Hagan would have won had the electorate been as young and diverse as the state's was in 2012.

Ebola: the cynical October surprise

Ebola never posed a serious public health threat to the U.S., and its virtual disappearance from discussion after the election ended underscored the point made by my colleague Joan Walsh: that the Republican and media-generated hype about the virus, with demands for travel bans and drastic, disproportionate emergency measures, was based purely on cynical fearmongering.

Of course, many Democrats, including Kay Hagan, frantically responded to the GOP's Ebola mania by endorsing travel bans themselves. This proved counterproductive; while most Americans early on approved of the government's response to Ebola, a majority of those who voted on Election Day did not.

Since it was an even-numbered year, it was inevitable that the GOP would rely on its old playbook of stoking fear and division as the election approached. But nobody could have predicted at the beginning of 2014 that Ebola would be their political weapon.

Cory Gardner's decision to run for Senate

As the new year dawned, Democratic Sen. Mark Udall of Colorado seemed to have caught a big break. His most likely GOP opponent, Ken Buck, was an incendiary Tea Partyer whose extreme views and sexist rhetoric doomed his 2010 candidacy against Sen. Michael Bennet. Congressman Cory Gardner, who was also extremely conservative but boasted better media training, had decided to sit the race out, even though GOP bigwigs thought he was the party's best shot to defeat Udall.

But in March, Gardner reversed course and announced that he would challenge Udall after all; his U-turn also cleared the GOP field, as Buck opted to run for Gardner's House seat instead. Gardner willingness to pander to groups he had alienated with his hard-right views -- women, immigrants and people who want clean air and drinking water, for instance -- helped Gardner keep the race close from the moment he got in, and on Election Day he ousted Udall, who just one year before had looked like one of the Democrats' safer bets for re-election.

An improving economy that didn't help Democrats

Although the fundamental political dynamics of 2014 meant that Democratic losses were all but assured, the Republicans' pickup of nine Senate seats and 13 House seats -- in addition to big gains at the state level -- does look a bit mystifying when one surveys the improving economic climate. Unemployment finally fell to below 6 percent this year, as employers' years-long streak of adding jobs continued. The economy continued to grow, the stock market had improved about 115 percent since Obama took office, and gas prices remained low.

To be sure, many Americans had stopped looking for work altogether during the economic slump, leading to a remarkably low labor force participation rate. But even those who most benefited from the Obama recovery turned sharply against Democrats this year, and the lack of a coherent Democratic message on the economy looks nothing short of puzzling. That the party did not tout its achievements -- and make a forceful case for government action to help those whom the recovery has left behind -- speaks poorly of its strategic finesse.

Shares