There are some readers who finish every book they start as a matter of principle. However, I put it to you that these are not the sort of people who need to review at least one book per week. Working critics practice a particularly severe form of literary triage. Some of us never get past the first page if the writing is clunky or downright bad, and most of us will abandon ship by about page 60 if the vessel has clearly gone adrift. Why slog onward when we can use that time to find and read books we can wholeheartedly recommend?

No doubt we miss out on some decent books this way, but few statements are less persuasive to a potential reader than, "It starts getting good after the first 150 pages." (There's only one novel about which I can say with confidence that it's absolutely worth persevering for 100 pages, even if you're feeling a bit bored: Neal Stephenson's "Anathem." You won't regret it.) As a rule, the first chapter of any book is the most polished because a lot more work goes into it. Authors and their agents know that if they want to land a contract, this is the piece of writing that must hook an editor. Chances are very, very good, that if the first couple of chapters are DOA, the rest of the book isn't going to suddenly stand up and deliver a Pulitzer-grade performance.

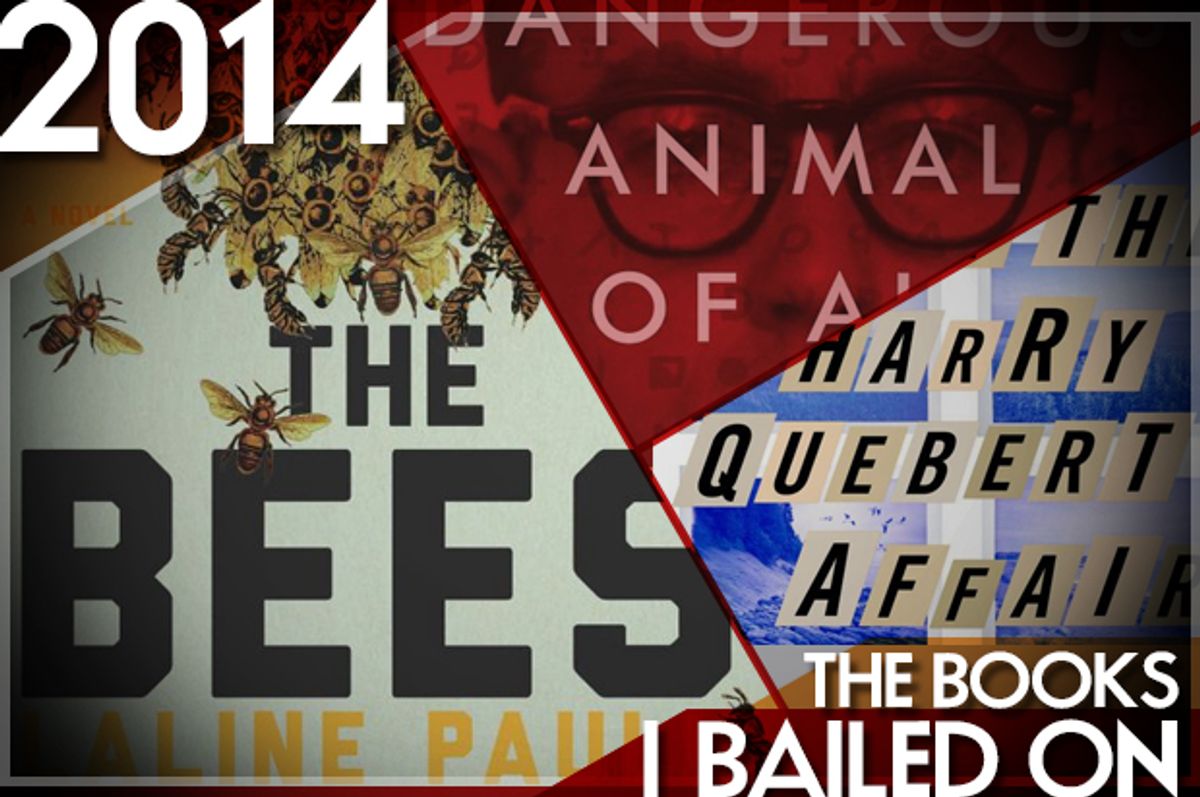

Nevertheless, there is more than one way a book (or a reader) can be bad, even the ones that begin engagingly enough. Here's a list of some the books I tried and failed to love in 2014.

Border Patrol Nation by Todd Miller

I'm going to begin this list with a caveat because Miller's book is about an important and underreported subject: the almost total non-accountability of U.S. Border Patrol officials in the years since 9/11 and the routine violation of civil rights that has resulted from it. Like a lot of reporters, particularly the very partisan ones, Miller isn't a gifted writer, and unlike their counterparts at magazines and newspapers, book editors are rarely able to put in the intensive sentence-by-sentence work that can transform a disorganized, inconsistent and overwrought text into a clear, persuasive piece of journalism. There is valuable information in "Border Patrol Nation," and there are readers who will find it worthwhile for that, but the definitive book on this issue has yet to be written. (If you're curious, the public radio program "On the Media" has an excellent and eye-opening report here.)

The Most Dangerous Animal of All by Gary L. Stewart and Susan Mustafa

Advance publisher promotion for this book stated that it described Stewart's discovery that he is the son of a serial killer who has never been apprehended. Only on the eve of publication was it revealed that the murderer in question was the notorious Zodiac Killer. Stewart, who was adopted as an infant, learned that he was the son of a man who bears a strong resemblance to the composite sketch made of the serial murderer who terrorized Northern California with random shootings and bizarre notes during the 1970s. That's about it as far as the evidence goes, although Stewart pads it out with a lot of sketchy conjecture. Worse, this unconvincing argument is conveyed in one listless cliché after another.

God'll Cut You Down: The Tangled Tale of a White Supremacist, a Black Hustler, a Murder, and How I Lost a Year in Mississippi by John Safran

Safran is an Australian documentarian who uses outlandish pranks to confront controversial subjects like religion and race; he's a cross between Michael Moore and Johnny Knoxville. While visiting Mississippi, Safran filmed a rally organized by a white supremacist named Richard Barrett, publicly confronting Barrett with the revelation that his DNA, obtained by deceit, revealed him to have "African blood." A few years later, Barrett was murdered by a teenage black neighbor he had hired to do yard work. Safran, who makes his own zany, neurotic and transgressive persona a prominent part of his work, decided to investigate, discovering that Barrett's killer had initially claimed that the attack was motivated by Barrett's aggressive homosexual advances. What could have been a fascinating account of the complexities of race and identity in a small town is marred by Safran's annoying self-interjection -- but even more so by his unreliability. As soon as I learned that he had lied to his documentary's audience about stealing Barrett's saliva for the DNA test, he proved himself too untrustworthy a narrator in a story that calls for careful and selfless reporting.

The Bees by Laline Paull

This novel can be aptly summarized as "Watership Down" with bees. The main character, Flora 717, is a low-caste worker bee with the ability to secrete royal jelly, a substance used to feed larvae and queens. As a trope, her situation is both too familiar (a lowly individual in a hierarchical society who is revealed to have special gifts) and too weird. I do not doubt that Paull is true to the life cycle and behavior of the insects, but their group mentality is utterly alien to the popular narrative the author wants to tell, with its focus on individual self-determination. And besides, the larvae and the royal jelly really grossed me out. Unlike Flora 717, I'm only human.

The Antiquarian by Gustavo Faverón Patriau

In the never-ending quest for a Latin-flavored novel that can recapture the old-fashioned, Dumas-style fun of Carlos Ruiz Zafon's "The Shadow of the Wind," this tale by a Peruvian author, translated from the Spanish by Joseph Mulligan, looked so promising. At the center of its baroque plot, set amid a bickering clique of book collectors, is one unfathomable murder and perhaps two more -- including a victim choked to death on torn-out pages. But the prose is so ornate and affected, so clotted with adjectives and fevered descriptions, that the novel lands in exactly the wrong spot on the line between sheer entertainment and art. It's too silly to be deep and too pretentious to be fun.

The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair by Joël Dicker

A huge bestseller in Europe, this novel, written by a Swiss but set in New York and New England, offers American readers a hilariously misjudged portrait of literary and small-town life in those places. From the preposterous success of the narrator's first novel -- which gains him a level of fame more plausible for, say, Leonardo di Caprio after "Titanic" -- to his efforts to clear his literary mentor of the charge of murdering his teenage girlfriend, everything is at least a little off. A convenience store clerk in a highway rest stop recognizes the hero because the shop used to sell his book and everyone in small-town New Hampshire would be totally cool with an affair between a 34-year-old man and a 15-year-old girl, provided they were really and truly in love. Dicker's endless gaffes were almost laughable enough to sustain this reader's interest, but only almost. And certainly not for 650 pages.

Shares