What’s worse than watching your child face a cancer diagnosis? How about having your child with cancer taken from you, and forced to undergo a treatment she vehemently does not want?

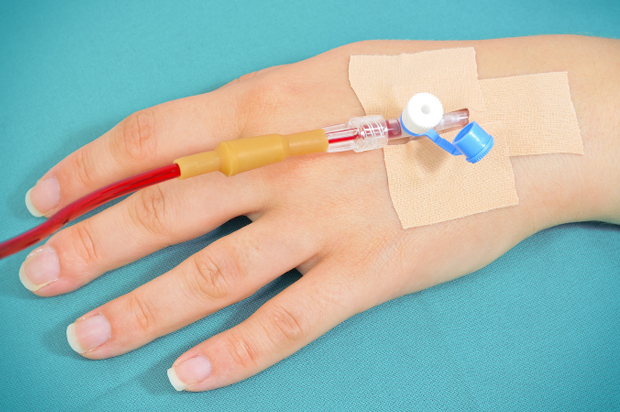

In Connecticut, a 17 year-old girl with Hodgkin’s lymphoma has been removed from her home and placed in protective custody, where she will receive chemotherapy. The girl, known in court papers only as Cassandra, was diagnosed in September. Her doctors recommended chemo, but, with the support of her mother, she refused. In November, the state’s Department of Children and Families won temporary custody of the girl, and, as CBS News reports, “ordered her mother to cooperate with her daughter’s medical care under DCF supervision.” She received two treatments before running away, and subsequently was placed in protective custody. The family’s attorney has challenged the state’s decision, saying, “It’s a question of fundamental constitutional rights — the right to have a say over what happens to your body and the right to say to the government, ‘You can’t control what happens to my body.'” The case will go before the Connecticut Supreme Court in Hartford on Thursday. She girl is currently at a local hospital.

On Wednesday, the girls’ mother, Jackie Fortin, spoke out about the case, telling CBS News, “She does not want the toxins. She does not want people telling her what to do with her body and how to treat it.” Fortin says that even if the chemo drugs are killing the cancer, “They are also killing her body. They are killing her organs. They’re killing her insides. It’s not even a matter of dying. She’s not going to die.” But the state disagrees – the DCF’s Kristina Stevens asserts that “We really do have the expert testimony, the expert advice of physicians who are saying unequivocally if she does not get the treatment that she needs she will die.”

I have two daughters of my own, including one who’s a teenager. I’ve also been through my own experience of Stage 4 cancer, and the thought of my children ever enduring anything like it is right up there among my worst nightmares. My instinct tells me that if my high school-aged daughter, so full of dreams and plans, were diagnosed with cancer, I’d do everything in my power to assure she had the best doctors and the most hardcore, get rid of the beast and we’ll figure out how to deal with the side effects later treatment on the planet. I believe I would fight for her life a hundred times harder than I fought for my own, and trust me, my two years of treatment were no day at the beach.

But as my children grow, I am also learning every day how to let them make choices for themselves that are different from the ones that I would make for them. Hard choices. Painful choices. When your child is little, your job is relatively simple – you advocate for her. You decide what’s in her best interests, and then you do that. As she gets older, though, she’s going to start to tell you what she believes her best interests truly are, and they will frequently conflict with yours. Loving your child means putting in the work of constantly adjusting your relationship, of knowing when to do for and knowing when to let her do for herself.

Cassandra’s mother does not seem to be waging this particular inner struggle. Her support for her daughter appears to stem from an unreserved approval of her choice. It also appears to arise from a belief – one the doctors seem not to agree with – that she can survive without chemo. That’s a wager I wouldn’t want to make, one that would break my heart if my child did. But Cassandra is not my child and she is not the state of Connecticut’s child either. She is not a toddler being deprived of food. She is a young woman of nearly legal age who is being denied a say in her own medical treatment, who has been removed from her family in a grotesque parody of looking out for her well-being. “Without me, standing by her side, while she’s losing her hair. Getting sick, throwing up,” Fortin says. “This is not right.” CBS reports, chillingly, that “The family searched for alternative treatments and second opinions, but a judge ordered Cassandra to undergo chemotherapy.”

No one likes to entertain the thought of a young girl potentially dying when there are lifesaving options readily available to treat her. But neither medical ethics nor the state’s duty should ever, ever be about taking extreme measures to simply extend life, without considering the wishes of the patient or the quality of life she wishes to have. Instead of being able to be there for her, Cassandra’s mother can only see her on two supervised visits a week. Instead of helping her deal with her illness, she has to wage a legal battle on her behalf. And that’s more than cruel and morally indefensible. It’s downright sick. Fortin, meanwhile, says of her daughter, “I’m proud of her. I am proud of her for standing up and fighting for what she wants and what she doesn’t want.”