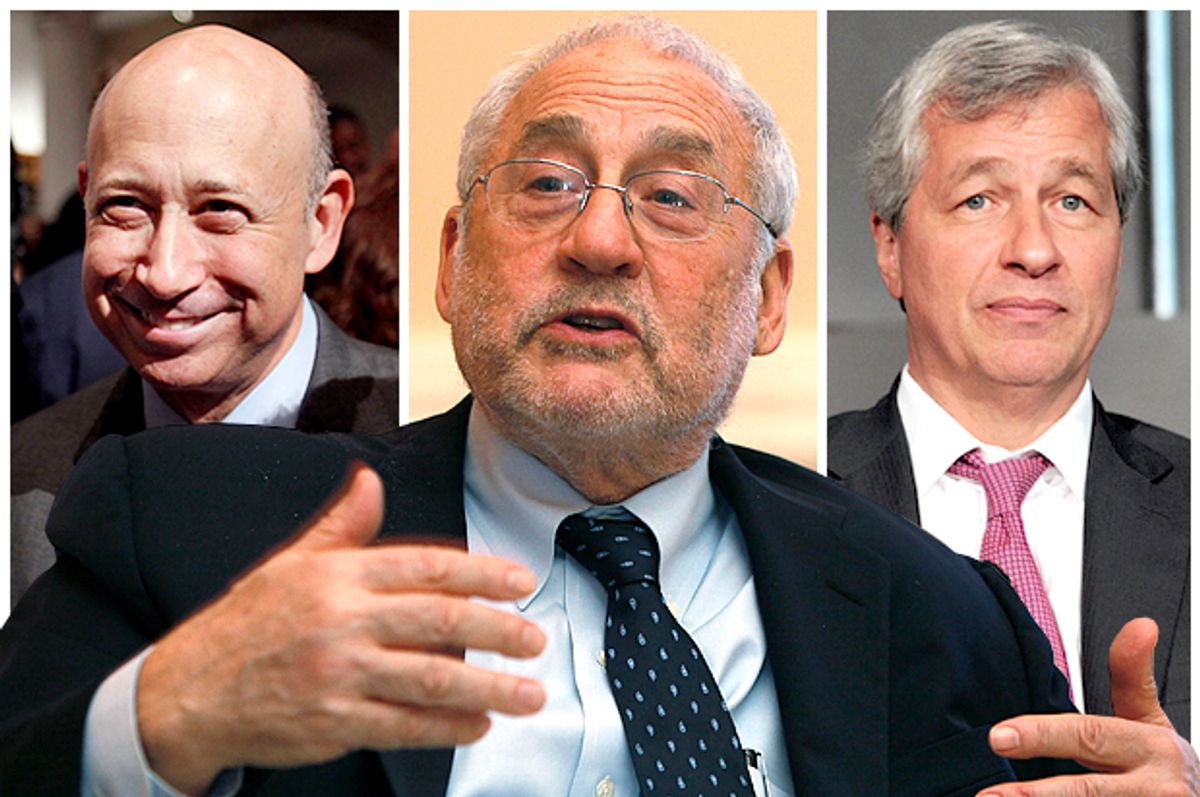

If the government were creating a new panel to advise on financial regulation, it would make sense to include a Nobel Laureate considered one of the most influential living economists. Yet Joseph Stiglitz has been barred from such a panel, telling Bloomberg he was out because “they may not have felt comfortable with somebody who was not in one way or another owned by the industry.”

The fight to keep Stiglitz off the panel is indicative of a much deeper problem — how the financial industry manipulates the regulatory system. The financial industry does not want Stiglitz on the panel for a simple reason: he has committed the crime of advocating for a modest financial transaction tax. Stiglitz argues that while financial markets normally serve the important function of capital intermediation, some forms of trading, like high-frequency trading, make markets less stable and amount to making money by moving money around. To reduce the incentives for such trading while raising revenue, he has put forward the possibility of a tax on some forms of short-term trading. Such a proposal has gained traction within academia and is already being implemented in Europe. (And it actually used to exist in various forms in the United States.)

Instead of preeminent financial reform experts like Stiglitz, many key regulatory and advisory positions are taken by those who loosen the leash on the financial industry. A perfect example is the recent nomination of Antonio Weiss to be the treasury undersecretary for domestic finance. Weiss has merger and acquisition experience, but as Simon Johnson notes, no domestic regulatory experience — illustrating in dramatic terms the revolving door between Wall Street and government. Research by Sophie Shive and Margaret Forster finds that this practice is pervasive and increasing. They write that, “the number of ex-regulators employed at financial firms increases by more than 55 percent” from 2001 to 2013. A 2010 CBS analysis finds more than four dozen former Goldman Sachs employees had high-level positions in government. This revolving door is part of what led us to the last financial crisis.

The influence of finance over policy goes deeper than simply revolving-door politics. Nicholas Carnes tells Salon that, “when members with finance backgrounds vote on roll calls, they seem to vote against labor more often than other members.” He finds that for every 100 bills related to labor issues, members of Congress who used to work in finance vote against workers on 3.5 more bills than their colleagues (a statistically significant difference). The rise of finance over politics has had important political consequences: Christopher Witko writes, “financial deregulation was one policy translating the political power of these actors into economic outcomes.” This political power was facilitated by the rise of money in politics, although research by Nomi Prins suggests that cozy relationships between powerful financiers and politicians have existed for decades.

A perfect example of this influence is the recent CRominbus bill (so named because it was both a continuing resolution and omnibus spending bill, making it a massive and high-stakes piece of legislation), which contained extensive deregulation measures. The original version of one of the bill's key provisions was actually written by the finance industry. (Seventy-five of its 85 lines came from a Citibank proposal.) Lo and behold: The average member voting in favor of the bill received $322,00 from the FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) industries, while the average member voting against the bill received only $162,000 from those industries. FIRE companies have dramatically increased their spending on lobbying in recent years, from $609,523,625 inflation-adjusted in the 2000 cycle to $996,406,725 in the 2012 cycle. Even IMF researchers linked lobbying to the rise of subprime mortgages and the opaque securitization schemes that left the financial crisis on a precipice. These attacks haven’t abated: Last week a new bill was introduced to further water down Dodd-Frank and other key financial regulations.

Domestic financial regulators need to include advocates for financial sector regulation like Professor Stiglitz. There is some bright news, like the recent appointment of a fomer community banker to the Federal Reserve. But this is only a first step: Congress should listen to Stiglitz and pass some form of a financial transactions tax. A pilot project could take place in New York by simply lifting the 100% reimbursement rate on a tax already on the books. In Congress, Representatives Harkin and DeFazio have already proposed a bill that would have generated $350 billion between January 2013 and 2021. But changes to the industry won’t happen until the government pursues stricter lobbying regulations and appoints strong financial sector regulators.

Lenore Palladino is vice president of policy & outreach at Demos.

Shares