In 2013, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, eloquently described the burden of writing as a person of color in America: "We battle for existence in real life as well on the page. We must defend our dreams and our daily lives."

Ghansah's words, part of a beautiful meditation on the 2012 slaying of Trayvon Martin, "De origine actibusque aequationis," speak particularly well to the moment we're in: Violence perpetrated against black bodies seems like it's becoming more and more prevalent. But it's also as visible as it's ever been. And as the national discourse has intensified, so has the need for thoughtful writers of color who can battle in real life and on the page.

Now, more than ever, America needs to hear what we othered voices have to say.

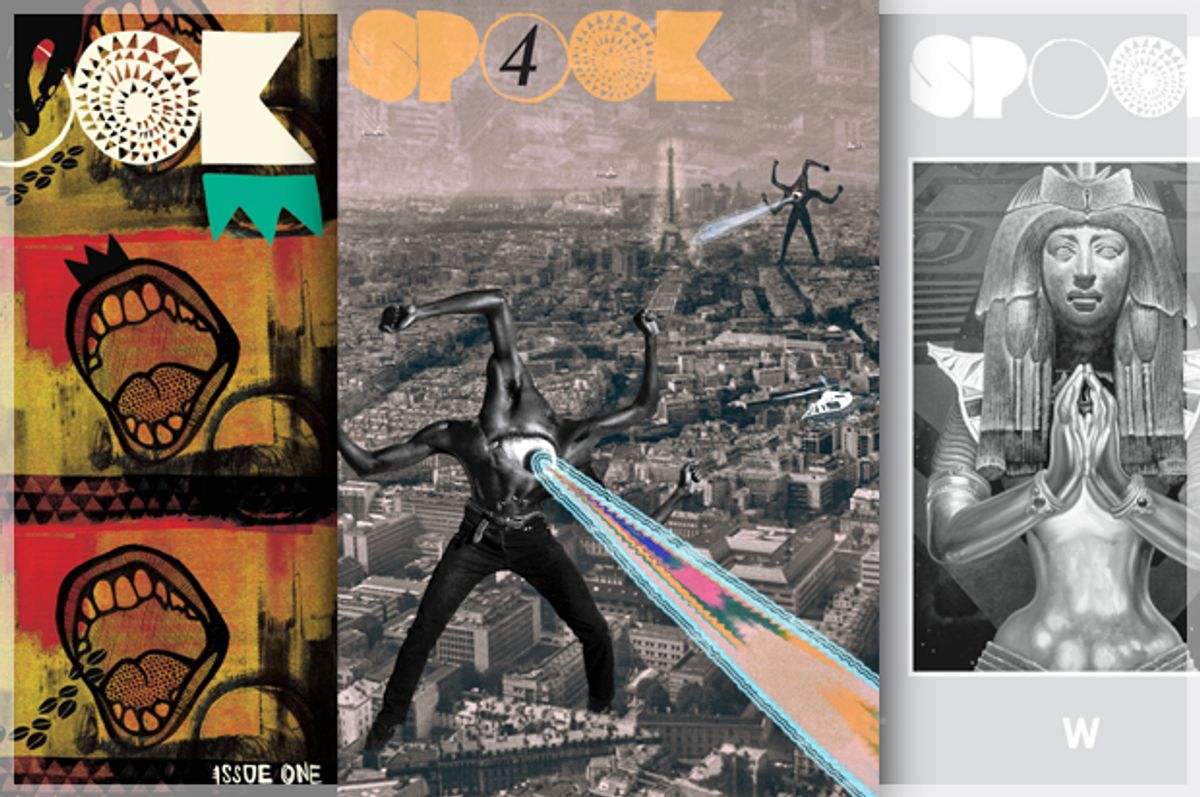

I thought of this as I grabbed the recent issue of Spook magazine, a self-described literary mashup, which has been bubbling under the radar since it was founded in 2012. Spook is edited by Jason Parham, a young senior editor at Gawker, and as a print-only zine it features everything from essays to criticism to fiction to poetry and art. Spook reads like a literary journal, eclectic with beautiful prose, brilliantly cross-secting the diversity of American intellectual life. With ideas ranging from popular culture to politics, from contemporary literature to art movements, the magazine is as informative as it is transformative and unique.

I first stumbled upon Spook reading the work of Cord Jefferson, formerly of Gawker, who now writes for “The Nightly Show With Larry Wilmore,” which premieres Jan. 19 on Comedy Central. Quickly I realized that many of my favorite writers, many of them young persons of color, have, too, written for Spook or been involved in some editorial capacity. A few names: Rembert Browne, Julianne Escobedo Shepard, Matthew McKnight, Kiese Laymon and others.

Spook’s latest issue is about Afrofuturism, an aesthetic movement built around the idea that African-Americans can simply exist in a new space, free of the burdens of the present, untethered from the forces of white supremacism. A place of just being. Numerous writers, poets, musicians, artists and thinkers have been associated with Afrofuturism: Octavia Butler, Rammellzee, John Coltrane, Outkast, Janelle Monae, Flying Lotus and, perhaps most notably, the esteemed science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany. In his seminal work, "The Necessity of Tomorrows," Delany stressed the importance of the idea powering the Afrofuturist movement:

We need images of tomorrow; and our people need them more than most. Without an image of tomorrow, one is trapped by blind history, economics, and politics beyond our control. One is tied up in a web, in a net, with no way to struggle free. Only by having clear and vital images of the many alternatives, good and bad, of where one could go, will we have any control over the way we may actually get there in a reality tomorrow will bring all too quickly.

Salon spoke with Jason Parham about Spook’s commitment to showcasing othered voices, diversity in media and publishing, and why Afrofuturism is so important at a time when America is at a crossroads.

I’m curious how you got interested in Afrofuturism and kind of what that means to you.

I can’t really pinpoint an entry point exactly. But the reasoning behind doing it for the most recent issue was a meeting of circumstances. One was, Spook for the first three issues was grounded in the past and in the present and I wanted to look forward and do something [that] imagined a future where we existed. And also with the whole Michael Brown, Eric Garner, all these black kids of color being killed — and that’s been happening throughout history but lately the frequency has increased. So I wanted to talk about a place where people I think existed. So that was my thought process behind it. I don’t know if we completely succeeded with it. But I’m happy with it.

This place you’re describing reminds me of my first run-in with Outkast. Something about them. Listening and watching them feels a bit like an out-of-body experience.

They’ve always been moving forward. They’ve always been one of the rare groups that has never compromised. They’re authentic in their vision of what they want and what they want to be. And kind of do their own thing. And it works. They're not the typical — I’m not saying there is a typical — but they're not typical mainstream “this is what a rap group should look like.” And then even coming from Atlanta way back when in the early 2000s and the late 1990s where you think the South is this one thing and you have these two black aliens coming out — one who’s wearing funky attire and the other one who’s too cool and it’s amazing and it blows your head away.

Spook has a real lyrical feel to it too. When I read it, it almost read like spoken word. A number of the essays read that way, particularly Terron Ferguson’s…

Oh, Terron’s was actually my favorite. That was a surprise too. Because Matt [McKnight], who’s my No. 2, he’s my senior editor and he works at the New Yorker — he helps me edit the whole thing — he’s like, “My boy Terron wrote something. It’d be really good.” I was like, “I don’t know. I’ve never heard of this dude.” I’m very particular with who I let write for Spook (laughs), which is why I think it’s been somewhat successful because there is a certain caliber of writers and art in there. But he goes, “Read it! Read it!” and I read it and I was floored by it. I was like, “This is so crazy and surreal.” Terron’s turning that into a larger book-length project. And Terron’s a lawyer, which is insane. He [Matt] was like, “I want to put this in there,” and I read it and was like, “Yes. We’re doing this!” (laughs)

Another artist I was glad to see in there was Missy Elliot. She’s Afrofuturist to the core…

That’s actually my entrance point to Afrofuturism. I was like: We’re doing Afrofuturism. We have to include Missy Elliot. Somebody has to write something on Missy Elliot. So I reached out to Julianne [Escobedo Shepherd], who’s phenomenal.

How do you find a lot of these writers for Spook?

The first issue I reached out exclusively to friends. And I blind-emailed a few dream authors — Justin Torres, and a few others that I wanted to be in the book. Some of them wrote back to me. Some of them didn’t. But after the first two [issues] people started emailing me a little bit more, saying, “I’d be great for Spook” or “I have this that I think would work for your next issue.” So the third issue was the first one where it was half-friends, half-contributions or submissions from people I’d never met. The fourth, this one was, because it took me so long — I had just started at Gawker, had other things going on there — this, the fourth one, was mostly me just asking friends for favors again. But it’s fun.

It’s really a beautiful issue to look at, especially the cover, which is amazing…

Yeah, Ivan is amazing. He’s a young artist from Harlem, Ivan Forde.

With Spook, how did you get the idea? What started it and why?

Toni Morrison. I went to grad school for literature, African-American studies. And I had been reading a lot of black literature, contemporary like Morrison, [James] Baldwin, [Ralph] Ellison, Paul Beatty, Gloria Naylor. And Morrison, in reading a lot of her interviews, she has this quote: “write the book you want to read.” There are all these amazing literary magazines that aren’t journals. But none of them wholly, completely apply to me or include people I know or people that I think are deserving of the space in those publications. I was like, I know all these talented artists and writers. I should just do something myself. And so I did. I was going to do it once as a zine, a one-off, and then it snowballed into something bigger than me and I kept it going.

You have some solid, young writers who have written in past issues. Cord Jefferson and Rembert Browne are phenomenal…

Don’t tell them [laughs]…

So what publications are you referring to that you read a lot that don’t see writers of color?

The New Yorker, Granta, Harper's. Harper's is so white. And just coming across those, even those regular literary journals, the New York Review of Books. There’s always a few of us — Colson Whitehead, Zadie Smith, Junot Diaz, the big names. But there’s never a more nuanced, careful, thoughtful, complete vision of blackness. So I wanted to present that myself.

As of right now the magazine is print (except the free digital download that comes with the print subscription). Any idea whether you’re going to move to digital or do both? Or just keep it the way it is?

I don’t know. Because another reason I started it was because all the jobs I’ve had post-graduate school have been online, almost — working at the [Village] Voice, writing for Vibe, Complex, Gawker. So working online 24/7, it’s great and it’s fun and it’s exciting, but it’s also exhausting in a lot of ways. The Internet doesn’t cut off. You can’t shut it off. You can’t flip the switch and take a nap, which we need to do sometimes. So it [Spook] was my pushback against that. And I want to create something that people can hold and sit down with and appreciate. I’m not saying we can’t appreciate things that are posted online, because there is a lot of visionary, amazing, innovative stuff being posted online. But I think with me more so being a traditionalist a little bit, you know? Coming up in that old school magazine world where these are the magazines I’ve loved growing up and I wanted to replicate that in a way.

That’s interesting. I think what’s great about Spook is how it blends pretty much all forms together. You have poetry, short stories, essays, criticism …

Right. So if you’re going to present this portrait of communities of color that includes black writers, blond writers, brown writers, red writers it has to be a tapestry of things. It can’t just be one thing. So I wanted to definitely have a survey of all. I think the next issue, No. 5, will be a little bit different. It will be the photo issue. Probably just have a lot of art and maybe a few essays.

How conscious are you of the message, of the sequences of the artwork?

I mean, you can’t not be conscious of the message, in a way. Spook is a message. It’s a political statement.

What is that statement exactly?

It sounds so cliché but this is who we are. We’re here. We’re worthy also of being in this conversation.

You work for Gawker, which is a huge platform, and it’s getting exponentially bigger. I’m curious what it’s like to navigate the very white world of publishing.

I think it’s one of the reasons I took the job. I was really comfortable at Complex. They were good to me. I was making OK money. I was having fun. A lot of my friends worked there, still work there. But Gawker, like you were saying, is this huge platform that reaches people I wasn’t able to reach at Complex. So when Max became editor after John Cook left, and he was like, “We have this position open. I think you’re great. I want to drive more minority voices, women's voices on the site. I want to give them this platform to expose them more. I think you’re perfect to do that.” So it’s more I took the job because I wanted to bring other people with me and get their voices out there because Gawker for so long had this, not a myth, but they were this understanding that if you wrote something long at Gawker, this very important place, especially coming from the media world. They were very particular about who they posted on their website or what they posted. So to be given the keys to that and saying, “Oh, we trust you and we trust your vision,” I couldn’t say no to that. So it’s been fun. I’ve been there almost a year. I think a lot of the stuff we’ve done, a lot of it’s throwing things up and seeing what sticks and what doesn’t. But it’s been really exciting, man. It’s weird because the platform’s a lot bigger now. So you get a lot more trolls than you did at Complex, and you get a lot more hate mail. But that’s part of working online. You’re working it out in front of everybody. And it keeps you on your toes in a way.

Do you think Spook not being online insulates it from a lot of the trolls? Is that something you worry about when you’re considering taking it online?

No. Because I think the vision of Spook will still be pure no matter where, if it comes online. People have reached out and said we want to be involved and maybe help you bring this online. But I’ve been extremely reluctant to do that. I’m still going to hold onto it for a little bit longer and just exist outside of the Internet in a way. But working at Gawker doesn’t affect at all what I do at Spook, where I take it. It’s two separate entities. It’s good because a lot of the writers that I meet through Gawker I can maybe, possibly, eventually filter through Spook, or the writers I know through Spook I can filter through Gawker. So it works in that way. But in terms of the themes and the subjects and what we cover and what we talk about, the trolls can say whatever the hell [they want]. We’re still going to do our thing.

So who are some of your favorite writers of color? Who do you read?

I read a lot for style, for how writers are writing and substance. I’m really interested in the ways people write. I’m really drawn to the lyricality of writing and music. How things can sing and dance and jump on the page. But everybody writes in their own way and that’s fine. There are just certain types of writers for certain spaces. How somebody writes as a creative writer is not necessarily how they would write as a fiction writer and an essay writer.

I’m really drawn to artful authors like Justin Torres. He wrote "We the Animals." It’s 150 pages, but it’s the best book I’ve ever read. You can read it in a day probably. I don’t know how fast you read. I read really slow and I read it in a day. But I like to take my time. NoViolet Bulawayo. She just published a book in 2013 called "We Need New Names." She’s amazing. Rachel Ghansah — I like everything she writes. Ta-Nehisi Coates, obviously. (laughs) I was really into Hilton Als last year. I was reading "White Girls." And I’ve read his criticism in the New Yorker. Some of it is good, but his reporting was always so much better. It just seems a little more black. A little more, this is what I’m doing. I think writing for the New Yorker you get drowned in edits and research and fact-checking. And so all the stories basically sound the same by the time they're published. All the voices almost sound the same. All the big features. But Hilton Als, his long-form stuff, still sort of sounds like him. It’s very unique to his voice, I think. So reading "White Girls," reading a lot of his older reportage was amazing. I think Kiese [Laymon] is a amazing, obviously. I work with her a lot so it almost feels weird saying this, but I think she’s one of the most talented writers — Josie Duffy. She helps me edit Spook, but we met a few years ago. She’s written two things for me since I’ve been at Gawker. But she had been writing there before I started. She’s a lawyer. I wish she would just quit and just write because she’s amazing.

Who are people you would want to work with on Spook? Right now you’ve been pretty much working with black writers. Are you looking to expand that at all?

I think, going in, I always try to open up to all writers of color and artists of color. But it just ends up being 80 percent black writers and artists and 20 percent everybody else. I always try to make a very conscious effort to include all people within the journal, but I don’t know. It’s tough, though. Because I’m not connected to a lot of those communities. A lot of it’s me knowing somebody, or them not having the time, or just being too busy, or them just not responding. I ask a lot of friends when I start early on for recommendations from writers who aren’t black who they think would be great. And I’ll reach out. But sometimes it doesn’t work out. I’m happy with what we end up with. I’m proud of it. But I do try. I want the vision to be more vibrant. I’m not saying it isn’t. But I want it to reach further and go deeper. I think we’ll get there. It’s still early on in the process. I’m still figuring out how to put a magazine together so I’m just throwing things up and piecing things together.

I’ve seen you on Gawker take a very conversational tone, sometimes transcribing emails with friends and other writers. I’m thinking in particular of “The Curious Case of the New Black,” which you curated. Is that kind of what you were aiming for with Spook? Are you trying to have a conversation?

I’m trying to extend the conversation. I’m trying to say, we have a black president, we’re getting equal rights for same-sex marriages, we have a Latina on the Supreme Court, we might have a woman president next. So we’re in a very interesting and exciting time, and I think Spook is an extension of that in saying, “We’re worthy of being a part of this conversation and this is what we have to say.”

I think there is a momentum that has a lot to do with what’s going on in the world. But it’s like I was saying — how I’m at Gawker now. I’m in a place to help bring other people up to this plateau, giving them the willingness to speak out. The thing about 2014, there was a lot of fucking cultural appropriation by white people. A lot of very culturally specific black topics, Latino topics that were huge in media, and it felt voyeuristic, in a way, with all these white writers talking about it. So I think you’re starting to see a lot more of us opining and reporting on stuff that’s important to us and talking about slang terms like “Bae” or Migos with rigor and intellect.

What is your goal for Spook in the future?

I want Spook to exist horizontally. I want to have a program around Spook — have events, podcasts, talks, maybe an exhibit. The idea of Spook was that I want it to be constantly evolving. Once I determine who’s writing it, who’s publishing it. I’m like, “This is a free space. Whatever you couldn’t do somewhere else you can do here.” It’s why you see writers like Rembert [Browne] writing about home in one issue and then writing about his experience going to Dartmouth as a black man. Or how Cord [Jefferson] is negotiating this relationship with being in the airport and seeing these people being demoralized and how that affects who he is. So it can be all these things. It can be an amalgamation of things and ideas and thoughts. It’s just a matter of making sure they bounce off each other and they're organic in a real way.

Shares