These are trying times for the American labor movement. Employer backlash; the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which restricted union activities and allowed states to pass "right-to-work" laws; and deindustrialization have led to a decades-long decline in union membership, a harsh reality underscored by Bureau of Labor Statistics figures released last week. The BLS reported that the union membership rate among wage and salary earners dipped to 11.1 percent in 2014, down from 11.3 percent in 2013. Those figures compare with a union membership rate of 20.1 percent in 1983, and they represent a drastic fall from unions' 1954 peak, when nearly 35 percent of wage and salary earners claimed union membership.

In recent years, Republicans governors have done their part to further erode union power; Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker infamously stripped public employees of collective bargaining rights, signing a measure that sparked an unsuccessful recall campaign in 2012. Since Walker signed the union restrictions, known as Act 10, public employee union membership has plunged in the state. In nearby Michigan, long a fortress of labor strength, Republican Gov. Rick Snyder signed legislation making the Rust Belt state a right-to-work one, meaning that workers wouldn't have to pay union dues even with union officials negotiating for higher wages and benefits on their behalf. Though supporters couched their arguments in terms of free choice, the real intent of right to work laws is to gut trade unions, whose bargaining clout is inevitably reduced once workers opt to freeload and, as a result, union funds dry up. Last year -- the first full year Snyder's right-to-work law took effect -- union membership in Michigan plummeted 7.6 percent; right-to-work advocates cheered the news.

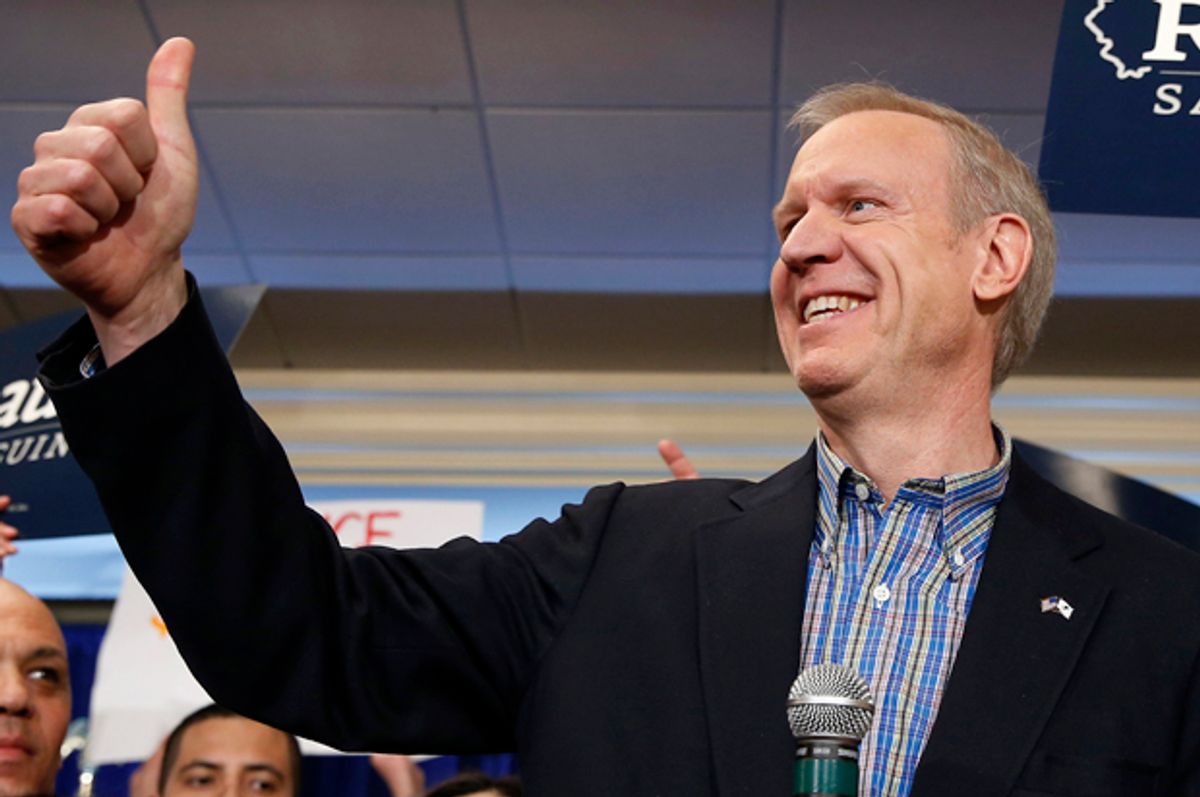

This is the context in which Bruce Rauner, the new Republican governor of Illinois (unionization rate: 15.1 percent), is looking to wage war on his own state's unions, with a particular focus on public sector employees.

Ahead of his State of the State address next week, Rauner is railing against unions as inimical to the state's business competitiveness, the Chicago Tribune reports. Appearing at a central Illinois community college on Monday, the governor threw his support behind efforts to curb union power.

"The states that are really growing don't force the unionization into their economy," Rauner said. "People can choose whether they join a union or not. I believe that's the right thing."

Rauner added that he isn't advocating a right-to-work law for Illinois -- at any rate, such a measure would be dead on arrival in the heavily Democratic state legislature -- but he endorsed allowing local voters to "decide for themselves" whether to establish "right-to-work zones."

But is Rauner right -- do states with less union power actually perform better economically than heavily unionized ones? Research by Richard Florida and Charlotte Mellander tells a different story. They looked at the relationship between a state's median income and its unionization rate, finding that unionized states perform better than non-unionized ones:

Of course, the correlation of higher union membership with higher wages (0.48) and median incomes (0.45) does not prove that higher unionization causes higher pay, but a key benefit of joining a union is that a worker has representatives who can bargain for her to earn a fair and decent living. A vibrant base of working and middle class wage earners, in turn, fosters consumer demand and boosts business performance.

Of course, the correlation of higher union membership with higher wages (0.48) and median incomes (0.45) does not prove that higher unionization causes higher pay, but a key benefit of joining a union is that a worker has representatives who can bargain for her to earn a fair and decent living. A vibrant base of working and middle class wage earners, in turn, fosters consumer demand and boosts business performance.

Moreover, Florida notes, "unionization levels are higher in states with more highly educated workforces and knowledge based economies." There's a moderate correlation between a state's unionization level and human capital levels, as well as the portion of the workforce in what Florida calls "knowledge, professional, and creative jobs." The inescapable conclusion? "Unions are not the cause of the serious economic and fiscal problems that are challenging so many American states, which are result of the economic crisis, collapsed housing market and massively reduced revenues."

But Rauner is unlikely to be moved by such facts. Although he campaigned as a pragmatic moderate in his successful bid to oust Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn last year, the billionaire investor is a dyed-in-the-wool Randian ideologue on economic issues; during his GOP primary campaign, Rauner even suggested reducing the state's minimum wage by $1 an hour, only to reverse himself amid a fierce backlash. Although questions concerning Rauner's business interests and controversial policy proposals helped the deeply unpopular Quinn keep the race close -- heading into Election Day, some surveys gave the incumbent a narrow lead -- Rauner defeated Quinn by a five-point margin. In his victory speech, Rauner promised Illinoisans a "new direction." They're now getting an idea of just what that new direction entails.

Shares