One of the very, very, very few mercies of the goddamn nightmare that is terminal cancer is when it can grant the person who has it a chance to say goodbye. And now, Oliver Sacks has something to tell us.

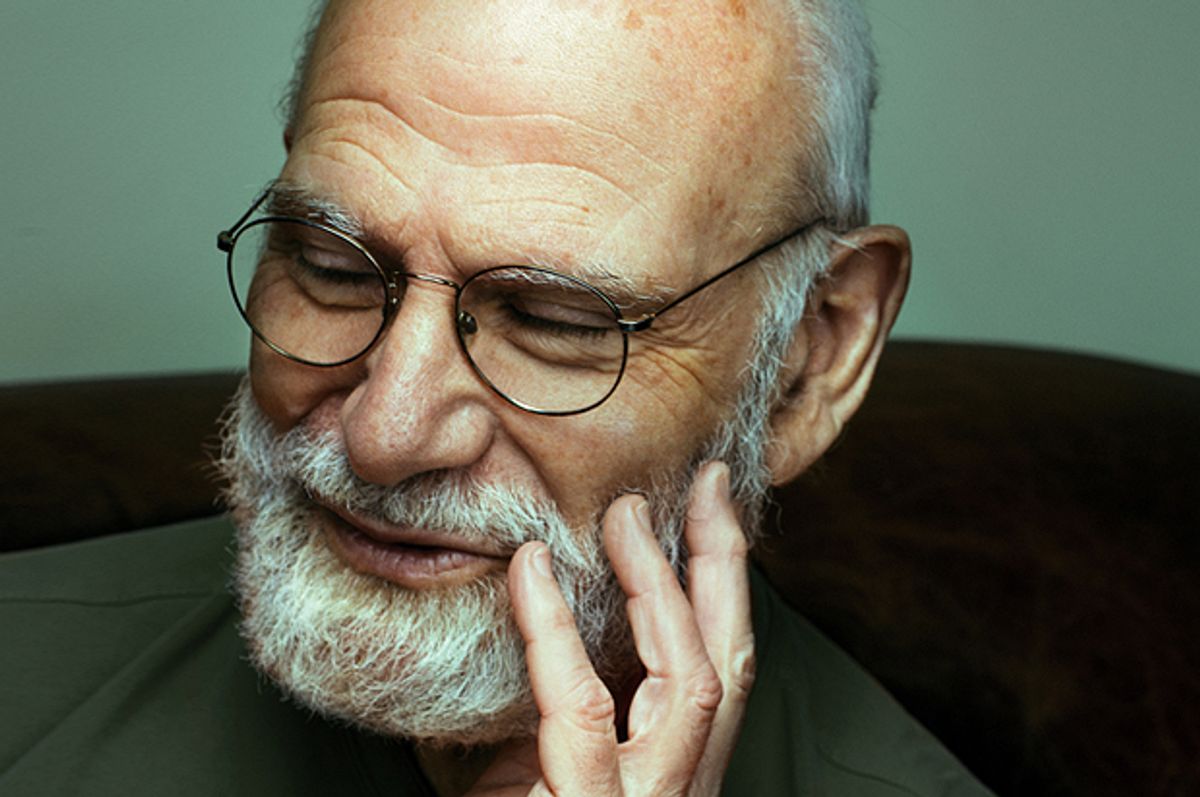

In an eloquent and clear-eyed op-ed for the New York Times Thursday, the 81 year-old neurologist, researcher and author of bestsellers like "Awakenings," "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat," "An Anthropologist on Mars" and "The Mind’s Eye" reveals the difficult news that "a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver." And he knows that that means.

Sacks has been writing about human body his whole professional life. In recent years, he has increasingly turned to his own body as a source of inspiration. In 2005, he was diagnosed with ocular melanoma and underwent radiation and lasering that took his vision from the affected eye. And though he says his particular kind of tumor only rarely metastasizes, he now finds himself in that "unlucky 2 percent." He isn't holding out unrealistic hopes; he is aware that "though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted" and what remains now is "how to live out the months that remain to me," because "I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can." And he's generously sharing that imperative with his readers.

He's following in some wise, if widely varying footsteps. Five years ago, Christopher Hitchens went public with his esophageal cancer diagnosis, and went on to chronicle his last few months with his typical unflinching eye, sending dispatches from "Tumortown" and railing against "pseudo-scientific nonsense." In a post near the end of his life, Roger Ebert said he was taking a "leave of presence" and said, "It really stinks that the cancer has returned and that I have spent too many days in the hospital. So on bad days I may write about the vulnerability that accompanies illness. On good days, I may wax ecstatic about a movie so good it transports me beyond illness." And in his memoir, he added, "We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try." Before he died in January, actor Taylor Negron wrote one last essay for XOJane, a rumination on being Hollywood's everyman and a declaration that "By letting go of what you thought was going to happen in your life, you can enjoy what is actually happening."

I've spent the past few years of my life watching some of the people I love most in this world die. I've watched them figure out, in their own special ways, how to do with grace and humor and love. I have grappled with my own serious illness and the very real possibility of an imminent demise, and asked myself whether I would see another spring, whether I would bake my daughters another birthday cake. I know what it's like to have to carry on through the mundane, unstoppable errands of life while wondering what it'll be like when your organs fail you, wondering how you will be remembered. And all I can say is that there's no one right way to do it. All I can say is how much admiration I have for the people who do it with the openness and honesty and sense of adventure that Oliver Sacks is doing it right now.

Sacks says that lately, "I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts" but promises "I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight." And while he admits he is not without fear, "my predominant feeling is one of gratitude," gratitude because, among other things, "I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers." That he is choosing to continue that special relationship, that he wants now not to withdraw but to share the journey, is a gift to all of us. And the gratitude, Oliver Sacks, is all ours.

Shares