"The biggest story in Hollywood this year was when North Korea threatened an attack if Sony released 'The Interview,' forcing us all to pretend we wanted to see it."

It was one of the first jokes at last month’s Golden Globes, delivered by Amy Poehler, and it killed. You knew there had to be some humor at North Korea’s expense. The ceremony was right in the middle of the Sony hacking fiasco, after all. There were significant questions about who attacked us and why, and larger questions about the value of free speech versus security. But at the same time, the Golden Globes has never been a hot spot for controversial comedy — it’s a largely middlebrow affair, aimed at pleasing the largest number of people possible. And so, when Tina Fey and Amy Poehler kicked off the show with a couple of zingers, we thought that would be the extent of it.

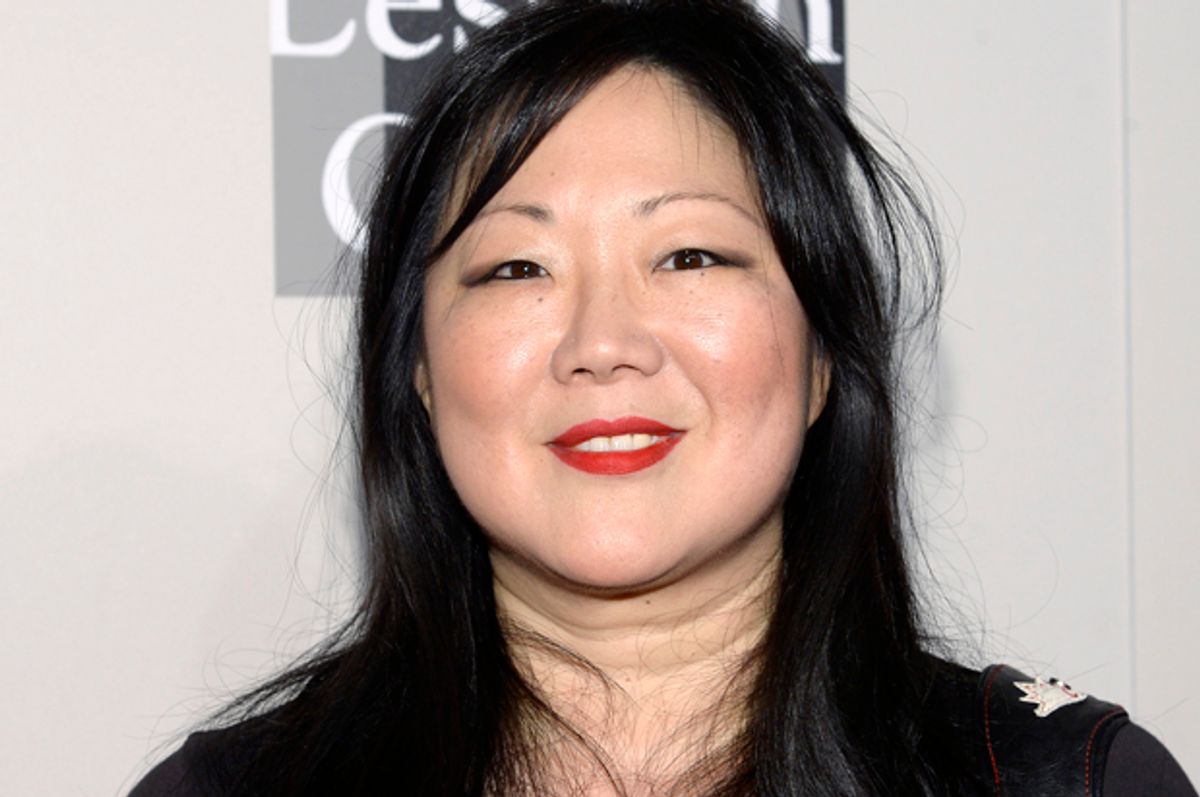

But then Margaret Cho got on camera, parodying a goose-stepping North Korean soldier while speaking in heavily accented English. And even though I laughed, it twisted me up inside. Not because I was personally offended — God knows I’ve experienced worse — but because I always worry what non-Asians will think. I grew up in an area where nearly every person was white, to the exclusion of other ethnicities, and so I approached my social interactions like auditions — I felt the responsibility to be a representative of my ethnicity to people who rarely had exposure.

So when Cho marched onstage, my fight-or-flight reflexes kicked in. I knew she was parodying a despotic regime, which deserved to be held up for ridicule. But I wondered if the less enlightened viewers among us would be able to tell the difference. After all, when “Sixteen Candles” became a box office hit, Asian American teens were subjected to the worst types of Long Duk Dong impersonations. I envisioned Cho’s words coming out of bullies’ mouths, accented English and all, and that troubled me. To what extent did Cho acknowledge and wrestle with these issues herself? What did she think of her own performance, and the response it’s received from the more critical voices in our country’s never-ending racial dialogue?

These were questions that I made a point to ask her when we spoke by phone last week.

Margaret Cho is no stranger to controversy, both major and minor. When she hit the stand-up scene, no one had ever seen a comedian quite like her. It was an exercise in juxtaposition — her Asian comedy, which played upon the tropes of fitting in and doing the "right thing" — and her LGBT comedy, which celebrated the myriad of ways that people could be different and rebel against societal norms.

Through all manner of trials and tribulations — a famously disastrous TV show, personal substance abuse problems, nasty, right-wing rhetoric — Cho continues to endure. Right now, she's on a roll. She’s the co-host of “All About Sex,” a late night show on TLC, where she engages in the types of conversations that would make a drag queen blush. Next month, she’s filming a brand-new TV special at New York’s Gramercy Theatre. It’s sure to be uncompromising, vulgar, political and real — sometimes, all at once. Some writers write and perfect their stand-up acts before ever stepping onstage, while others, like Louis C.K., take an idea and develop it over time. Cho says both approaches work for her, for different occasions.

“Sometimes, it’s better to have something completely written out and know exactly where you’re going to go. And then other times, it’s great to pressure yourself where you have to come up with something, where you’re working it out onstage,” Cho said. “I know what I’m going to say, but I definitely have a different experience every time I perform. You have to be very immediate and very present in your performance. There’s a lot to be said for kind of making it happen as it’s happening.”

Lately, she's been working on material about Joan Rivers, her friend of many years. Cho says Rivers was a big influence on her life, and working on stand-up material about her is a way to "deal with my own grief and sadness and wanting to talk about her, which helps.”

“She was just wonderful,” Cho said. “She was a big fan of my comedy, and I think that she saw herself in me, which is why we bonded and connected.”

“She always wanted me to remember how lucky I was — and how lucky that we both were — that we had jobs in comedy. Aging wouldn’t affect it, looks wouldn’t affect it. You could be who you were, and you didn’t have to worry about being a woman in Hollywood in the same way that other women worry about being a woman in Hollywood. We as comedians could work forever, and in fact, we’re better when we’re older, which I think is a great lesson,” she added.

When Rivers died, Cho paid tribute with an irreverent account of her funeral: "Joan Rivers put the 'fun' back in funeral." The highlights: Howard Stern’s eulogy, during which, through tears, he proclaimed that “Joan's pussy was so dry it was like a sponge – so that when she got in the bathtub – whooooosh – all the water would get absorbed in there! Joan said that if Whitney Houston had as dry a pussy as Joan's, she would still be alive today…"

Like John Cleese’s bawdy sendoff of fellow Python Graham Chapman (“Good riddance, the freeloading bastard, I hope he fries.”) it was a deliberate act of poor taste, a tribute to a person who had all but mastered that particular art. “[Rivers] would always say, ‘We were both ugly in high school, which is why we’re so happy now,’ and I would always say, ‘Speak for your fucking self! God!’” Cho recalled, with a laugh. “She was very much into the ugly duckling revenge story. We had conquered our way out of those moments, and got to have a voice and got to be empowered.

“Joan just said whatever. She didn’t care, and that was great. We all have fears in comedy, especially nowadays. You don’t want to say things to offend people, but comedy is really about offending people, if you’re doing it correctly. Joan was never afraid of anything.”

It’s hard not to notice some parallels between Rivers and Cho. Joan left the safety of Carson’s “Tonight Show” to start her own late night platform. When it was canceled (and her executive producer husband, Edgar, killed himself), Joan found herself blacklisted from the industry. She had to scratch her way, tooth and nail, back to the top — a process that took decades of career rehabilitation.

Cho also found mainstream success early, as the star of one of the first Asian American sitcoms on television in 1994. But this too was met with disaster — there were endless debates about her weight, her Asian-ness, whether she was too Asian or not Asian enough. Asians were themselves critical of the show, noting that Cho was the only Korean in a supposedly-Korean family and decrying what they felt were simplistic stereotypes. After the show’s cancellation, Cho’s career and personal problems bottomed out.

Today, she sees the show as a product of its time. She doesn’t have any feelings of resentment toward the recent success of “Fresh Off the Boat,” the first Asian American sitcom on TV since hers, or wonder why she wasn’t more successful.

“I realize that it couldn’t have been me, because of the time — the society didn’t support it,” Cho says. “Now, it’s a different time for a comedy that is about an Asian American family, because you can afford to be irreverent, you can afford to be very real. I think it’s great. I’m really proud and excited, and I think [“Fresh Off the Boat”] exists in the right time. I think I was too early 20 years ago, unfortunately.”

Cho has served as a confidante and friend to Eddie Huang, the writer of the memoir that “Fresh Off the Boat” is based upon, and has helped him throughout the development of the show. Like Huang, Cho understands the frustration of having a TV show purport to show your life. “All-American Girl” was allegedly based upon her stand-up comedy, even though her creative input was limited to nonexistent.

“The network had a problem with the title 'Fresh Off the Boat,'" Cho said. “The white people at the network were offended — which is such a weird thing. There’s a kind of white privilege that takes offense on our behalf. It’s a very subtle thing, but very racist in its own way. [The network president] wanted the show to be called “Far East Orlando.” Which I actually think is more offensive, because it really points out the fact that the [Huang family] doesn’t belong. Whereas being ‘fresh off the boat,’ you do kind of belong, but it’s on your own terms. It’s a subtle difference, but a significant one.”

“I was trying to help him by giving him examples from my experience. How hard it was for me to just survive. I didn’t have as strong of a sense of self as Eddie does now, so it was different," she added. "I was much younger in my development, and so I didn’t really know how to handle it. I was always thinking, ‘I just need a job, and ‘If I can just get this show on the air, they’ll figure it out later,’ but that was really the wrong approach for me. I wanted to let him know that he had all of the integrity and all of the work there already. He just needed to trust himself.”

“Fresh Off the Boat” addresses the race question head-on; it’s in the title, the marketing and the core humor of the show. Compare this to a show such as “The Mindy Project,” which, despite the lead’s Indian descent, rarely addresses issues of race. Her ethnicity simply is — an incidental part of a larger identity, and any jokes about it are fleeting and just as prescient as jokes about weight, or sex, or being a woman. Mindy Kaling herself has taken issue with the criticism that she doesn’t do enough to represent minority issues: “I’m a fucking Indian woman who has her own fucking network television show… I have four series regulars that are women on my show, and no one asks these other shows why there are no women or women of color.”

But to Cho, these issues are unavoidable, and given her own ethnicity, they can’t help but be addressed. “I don’t know how to experience anything other than from an Asian American perspective," Cho said. “I’m not as separated or removed from it.”

But what is the better course of actions for Asian Americans to take in Hollywood? Should we address the concerns of our people head-on and explicitly? Or should we deemphasize that part of our identity in favor of a more palatable, mainstream appeal? Is the latter progressive — that race no longer matters as it once did — or repressive? Is the former more authentic, or does it run the risk of stereotyping and pigeonholing us even further?

Which brings us back to the Golden Globes, and Cho’s repeated cameos throughout the night. When I asked her about it, and why people were offended, her reaction was the same one that she held toward the white network executives at ABC.

“There’s a lot of white privilege there too,” Cho said. “There was a lot of white people reacting towards an Asian caricature, and reacting on behalf of people of color. What I found interesting was that I was the only Asian American person at the awards. I was the most Asian American thing about the awards! There were no nominees… I think Julie Chen was in the audience, but that was the only one I saw.“

“There’s no presence at these awards shows. Almost ever. That is, to me, more offensive that whatever I’m doing. I was acting on behalf of myself and [this problem of] Asian silence and Asian invisibility when dealing with something that’s very big,” she said.

It’s a fair point. I don’t need for people to be offended on my behalf — I want to be in control of my own narrative. But at the same time, Cho didn’t acknowledge that Asians could have been offended — to her, it seems a given that they would get it. And so I asked her, on behalf of my own perspective, what she thought about my concerns. About people misinterpreting her caricature. About the weight of expectation of being a so-called model minority, and the expectations I place upon myself.

“I can’t think that far in advance,” Cho said. “It’s not like we have that much visibility... Every image becomes so vitally important, because we’re really not given that many jobs or opportunities to speak. So, you don’t think about it that much. I’m also from a different generation; I’m just grateful for anything I get. I don’t know what I’m doing. And I’m sure it’s fine.”

It’s certainly a less exhausting way to go through life — one that is not burdened by metacognitive second guessing, where one is blindly trying to ascertain what is the best Asian -- whatever that is even supposed to be -- that one can be. Perhaps it’s a realist’s perspective, that Asian representation itself is the victory — that at least we are parodying our own people, rather than having a white person with taped-back eyes do it for us. And perhaps she is doing what more Asians should have the courage to do — make a mess, make a statement, and leave it for other people to sort out.

Shares