I suspect I can speak for most American Jews when I say: Before I’d watched even a single episode of “Star Trek,” I knew about Leonard Nimoy.

Although there are plenty of Jews who have achieved fame and esteem in American culture, only a handful have their Jewishness explicitly intertwined with their larger cultural image. Much of the difference has to do with how frequently the celebrity in question alludes to his or her heritage within their body of work. This explains why, for instance, a comedian like Adam Sandler is widely identified as Jewish while Andrew Dice Clay is not, or how pitcher Sandy Koufax became famous as a “Jewish athlete” after skipping Game 1 of the 1965 World Series to observe Yom Kippur, while wide receiver Julian Edelman’s Hebraic heritage has remained more obscure.

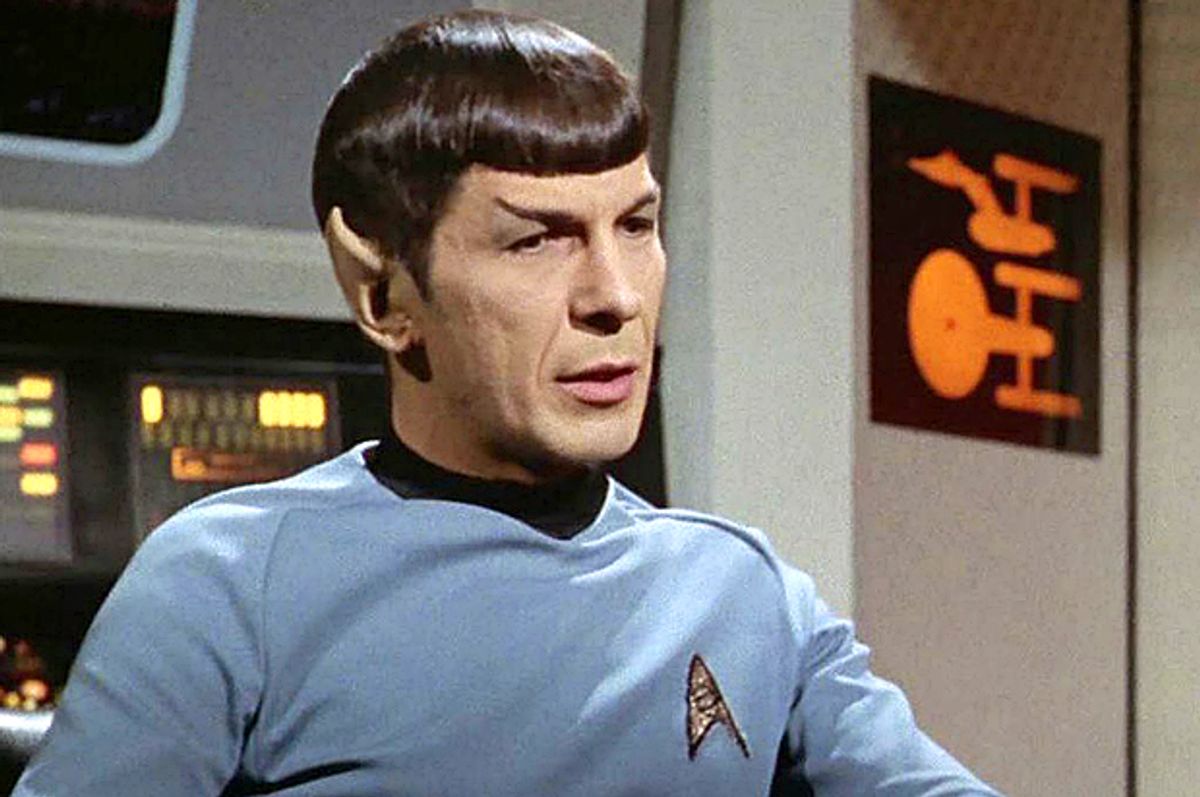

With this context in mind, it becomes much easier to understand how Nimoy became an iconic figure in the American Jewish community. Take Nimoy’s explanation of the origin of the famous Vulcan salute, courtesy of a 2000 interview with the Baltimore Sun: “In the [Jewish] blessing, the Kohanim (a high priest of a Hebrew tribe) makes the gesture with both hands, and it struck me as a very magical and mystical moment. I taught myself how to do it without even knowing what it meant, and later I inserted it into ‘Star Trek.’”

Nimoy’s public celebration of his own Jewishness extends far beyond this literal gesture. He has openly discussed experiencing anti-Semitism in early-20th century Boston, speaking Yiddish to his Ukrainian grandparents, and pursuing an acting career in large part due to his Jewish heritage. “I became an actor, I’m convinced, because I found a home in a play about a Jewish family just like mine,” Nimoy told Abigail Pogrebin in "Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish." “Clifford Odets’s 'Awake and Sing.' I was seventeen years old, cast in this local production, with some pretty good amateur and semiprofessional actors, playing this teenage kid in this Jewish family that was so much like mine it was amazing.”

Significantly, Nimoy did not disregard his Jewishness after becoming a star. Even after his depiction of Mr. Spock became famous throughout the world, Nimoy continued to actively participate in Jewish causes, from fighting to preserve the Yiddish language and narrating a documentary about Hasidic Jews to publishing a Kabbalah-inspired book of photography, The Shekhina Project, which explored “the feminine essence of God.” He even called for peace in Israel by drawing on the mythology from “Star Trek,” recalling an episode in which “two men, half black, half white, are the last survivors of their peoples who have been at war with each other for thousands of years, yet the Enterprise crew could find no differences separating these two raging men.” The message, he wisely intuited, was that “assigning blame over all other priorities is self-defeating. Myth can be a snare. The two sides need our help to evade the snare and search for a way to compromise.”

As we pay our respects to Nimoy’s life and legacy, his status as an American Jewish icon is important in two ways. The first, and by far most pressing, is socio-political: As anti-Semitism continues to rise in American colleges and throughout the world at large, it is important to acknowledge beloved cultural figures who not only came from a Jewish background, but who allowed their heritage to influence their work and continued to participate in Jewish causes throughout their lives. When you consider the frequency with which American Jews will either downplay their Jewishness (e.g., Andy Samberg) or primarily use it as grounds for cracking jokes at the expense of Jews (e.g., Matt Stone of “South Park”), Nimoy’s legacy as an outspokenly pro-Jewish Jew is particularly meaningful right now.

In addition to this, however, there is the simple fact that Nimoy presented American Jews with an archetype that was at once fresh and traditional. The trope of the intellectual, self-questioning Jew has been around for as long as there have been Chosen People, and yet Nimoy managed to transmogrify that character into something exotic and adventurous. Nimoy’s Mr. Spock was a creature driven by logic and a thirst for knowledge, yes, but he was also an action hero and idealist when circumstances demanded it. For the countless Jews who, like me, grew up as nerds and social outcasts, it was always inspiring to see a famous Jewish actor play a character who was at once so much like us and yet flung far enough across the universe to allow us temporary escape from our realities. This may not be the most topically relevant of Nimoy’s legacies, but my guess is that it will be his most lasting as long as there are Jewish children who yearn to learn more, whether by turning inward into their own heritage or casting their gaze upon the distant stars.

Shares