“Look what I got,” my father said, holding up a little plastic bag.

I’d never shot heroin before, but I was curious about it, and always open to any substance that would alter my consciousness. I sat down next to my father, the man I’d grown to trust above all others, and held out my arm. That was the first day I did heroin with my father, but it wouldn’t be the last. What started out as an experiment quickly became a habit, a way of existence.

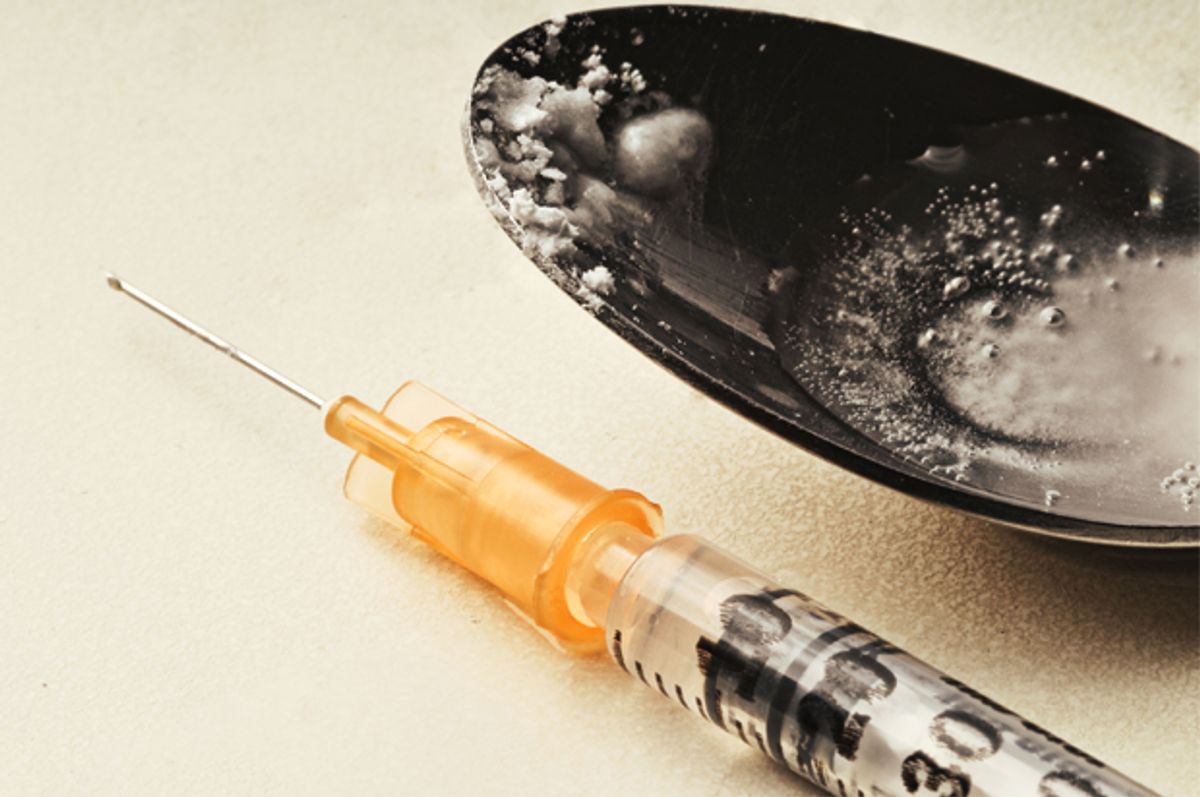

“People would think I was nuts to do this with my daughter,” my father said one afternoon as we sat in his room, surrounded by stacks of art magazines and CDs, sketchbooks and palettes. My father was a hoarder in the most creative, intellectual sense. “But this,” he gestured at the empty syringe and singed spoon on the table, “is a means to an end. Nothing else would facilitate the kinds of conversations we’ve had, the realizations we’ve come to.”

He was right. Heroin stripped away every painful memory that had ever stood between us, every trace of guilt and resentment, everything that had ever prevented anything but the purest possible soul communication. And contrary to what many would have you believe, heroin is not an instant, one-way ticket to ruin. Heroin did not take over my life – until the day it ended my life.

* * *

I can honestly say I never expected to become so familiar with a drug, but then, I never expected to become familiar with my father, either. I was 18 years old when his letters started showing up in my mailbox. Each one addressed in his trademark penmanship, some strange cross between calligraphy and a madman’s scrawl, the envelopes were postmarked from various Louisiana locations: Houma. Baton Rouge. Seemingly exotic places I’d never seen or heard of growing up in Stamford, Connecticut – the same town where my father was born and raised. Of course, by the time my second birthday rolled around, he’d already cheated on my mother multiple times and made his subsequent escape to the booze-soaked bayou. He would tell me later that he was doing me a favor, that I was better off without him all those years.

He was probably right, but I didn’t know it at the time.

As a stubborn, melancholy 18-year-old, all I knew was that my father’s letters were too little, too late. “Happy birthday, darlin’,” he wrote in the first letter. “Your birth was certainly one of the most memorable occasions of my life.” You could’ve fooled me, I thought, remembering the endless stream of birthdays that went unmarked by any sort of communication from my father. About a month later, he sent me a book, “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by Robert M. Pirsig. I would have liked the book if I’d bothered to crack it open. Instead, I stuffed it in my backpack with a roll of my eyes, thinking that with all the money he saved by not paying my mother child support he could’ve afforded a better gift. I said as much when the paperback tumbled out of my bag the next day during sculpture class and my friend Dan spotted it on the floor. “Thanks a lot, Dad,” he said, laughing. His snide comment made me feel better, like somebody understood. It shouldn’t have. In reality, Dan was less than a friend, just some guy I hooked up with occasionally because he was arrogant and disrespectful and, like so many young girls with “daddy issues,” that’s all I thought I deserved.

I didn’t mention Dan when I finally started writing back to my father, but I did mention my sculpture class, and the other classes on my schedule at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. The school was where my father met my mother in the late 1960s, and his obvious pride at hearing that I had been accepted at their alma mater made me ridiculously, unexpectedly happy. “Stay focused,” he wrote. “Work until you can’t stand not to.” I should have followed his advice, but I couldn’t, not yet. He couldn’t either, at my age.

In fact, as our correspondence evolved, I began to see that my father and I were more similar than I’d ever suspected. But it wasn’t until he sent me a certain poem that I would recognize just how alike we truly were.

My father didn’t write the poem (attributed to “Anonymous”), but it didn’t matter, because he could have – and as I read each stanza, sitting on my bedroom floor with tears streaming down my cheeks, I realized that the photocopied words could just as easily have been my own. I can’t remember those exact words now, nearly 20 years later, but the verses spoke of a deep-seated shame, an inherent sorrow and self-loathing carefully hidden from the world. How did my father know me so well? Only when I got to the last line, “I am an alcoholic,” did I get it: The poem was meant to serve as a sort of paternal mea culpa, not an eloquent declaration of like-mindedness. It ended up being both. Dan didn’t understand me, nor did any of the equally arrogant, disrespectful guys who preceded him, but my father did – even if he didn’t know it yet.

I was not, and would never become, an alcoholic. In that respect, my father and I were different. I was, however, vulnerable to vice and chronically depressed. In that respect, we were the same. When my father decided to move back to Connecticut permanently, our mutual demons would bond us in a way that no idyllic, two-parent childhood ever could have.

The first pharmaceuticals my father “turned me on” to were antidepressants – and in doing so, he probably saved my life.

“If these had been around when I was your age, I probably never would have started drinking,” he told me over iced tea and American Spirits in his mother’s backyard. My father didn’t introduce me to cigarettes; I’d been smoking for about six months before his return. We filled countless ashtrays together, talking about anything and everything: the time my father ran away with Timothy Leary as a teenager; his preferred brand of oil paints; how to make an authentic Louisiana gumbo. When he spoke, my father’s blue eyes burned like white-hot fire. When he laughed, he positively roared. But my father’s body was different than I remembered from my early childhood. A few years earlier, a hit-and-run driver had shattered his once lanky frame. His back now had a slight hump and his rib cage protruded. There was a jagged scar across his forehead. He was in a near-crippling amount of pain at all times thanks to a degenerative bone disease brought on by the anti-seizure medications he took when he was still drinking (it was a seizure that led to the hit-and-run). As a result, he’d begun consuming a staggering amount of Oxycontin, prescribed to him by more than one doctor.

“I could use an existential painkiller,” I joked one afternoon when we were hanging out, talking about life and watching Eric Clapton concert videos. My father pointed to a tidy pile of blue powder in a tin on his dresser and handed me a short red straw. Having gone through a significant cocaine phase myself, I knew what to do with that straw. Existential painkiller, indeed.

That’s how it started. Whenever I showed up at my dad’s, there would be a pile of blue powder waiting for me – I didn’t even have to ask. One night, as I was driving to his place, “Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones came on the radio. Just a shot away. I got a funny feeling in the pit of my stomach. When I walked through the door, my father’s face lit up. There was a gleam in his eye I’d never seen before.

I should say that the days I spent doing heroin with my father were a waste of time – a sordid void from which I would never return. But that would be a lie. Those days were among the happiest of my life.

I never wanted to believe that my father’s absence all those years was responsible for the nagging deficiency I’d felt growing up, the stunted sense that I was always somehow missing something – some essential fuse that would have made my fundamental human wiring function the way it was supposed to. To chalk that unrelenting emptiness up to textbook feelings associated with paternal abandonment seemed too easy, too reductive. Surely the truth behind my damaged psyche was more complicated than that – except, it wasn’t. Because finally having a relationship with my father made all of those feelings go away. Spending time with my father, shooting heroin, I felt complete. Whole. Strong. Alive – until the day I died.

It was a more powerful strain than what we usually got, which is often the case when an overdose occurs. The last thing I remember before being swallowed up by blackness is holding my arm out for my father, like so many times before. I was shocked awake on a cold steel table in the ER. I screamed at the brightness of the lights.

“Well. We didn’t think you were coming back,” said the doctor, looking at me in disgust.

When they let my father in to see me, his eyes were the bluest I’d ever seen them.

“You joined the club,” he said.

“What club?” I whispered.

“The flatliners club,” he said.

That’s the last time I saw my father alive. I closed my eyes again and he was gone, and though he tried to contact me after I went back home to my mother’s house, I didn’t answer his calls or return his messages. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to see him – on the contrary, I missed him so much it twisted my stomach into knots. It wasn’t even that I blamed him for the overdose. It was simply that I didn’t trust myself around him, was terrified that his presence would make it too easy to start using again.

Besides, how could I justify my relationship with my father to the rest of my family after what happened? Already suspicious of our relatively recent alliance, my near death experience merely served to confirm their worst fears about him. And so, just as my father had disappeared from my life all those years ago, I disappeared from his. In the end, the demons that brought us together are what drove us apart. Staying away from him was the hardest thing I’d ever done. Several years later, when he slipped at last into the same darkness that almost claimed me forever, a part of me died with him.

To mark Salon’s 20th anniversary, we’re republishing memorable pieces from our archives; this piece originally appeared in 2014.

Shares