America is caught in the throes of the 114th Congress. May the world take pity on us. They are so gridlocked they can’t even agree that sex trafficking is a bad thing. It is certain, even years before the next election cycle, that we will be calling 114 Congress the worst ever, just as we called the 113th Congress the worst ever.

America is caught in the throes of the 114th Congress. May the world take pity on us. They are so gridlocked they can’t even agree that sex trafficking is a bad thing. It is certain, even years before the next election cycle, that we will be calling 114 Congress the worst ever, just as we called the 113th Congress the worst ever.

Then again, that wasn’t true. The 112th was actually the worst ever, at least statistically. The 113th passed 296 laws. The 112th passed only 283. In any case, even those meager numbers should be judged on a curve. A third of the laws passed in these two Congresses were ceremonial in nature, like the historic last measure passed by the 113th: a commemoration of the "centennial of the passenger pigeon extinction.”

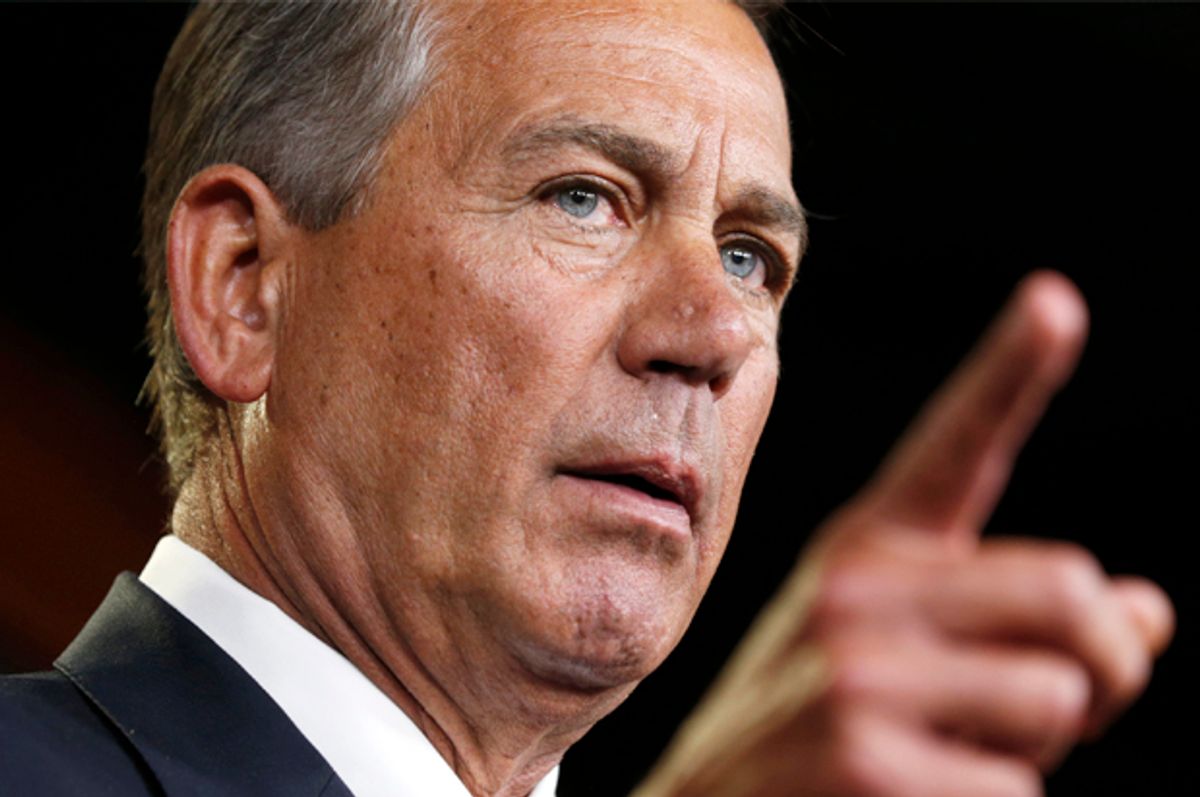

In 1948, Harry S. Truman won an historic surprise election by railing against the “Do Nothing” Congress. That sorry body passed 900 bills. One wonders what Truman would have said about today’s legislators? House Speaker John Boehner memorably asked that the Congress not be judged on the number of laws it passed, but how many it repealed. Well, that would be zero. Sorry, Mr. Speaker.

Meanwhile, we had philandering congressmen, indicted congressmen, cocaine arrests, and one filibuster during which Dr. Seuss’s “Green Eggs and Ham” was recited.

There was the unending Benghazi blather that concluded nothing nefarious went on leading up to that tragic incident. There were the three billion attempts to repeal Obamacare. Nothing meaningful passed to aid the economy, rebuild infrastructure, or deal with millions of illegal immigrants in a sane and compassionate manner. No budget could be agreed upon.

Meanwhile, money roars into the system, thanks to the Supreme Court’sCitizens United decision, and our elected officials appear to be bought and branded by moneyed interests. Cynicism is rampant, and it is no mystery why approval of Congress is approaching single digits. Still, were 112 and 113 the worst Congresses ever? Probably. But there were a few that approached them, simply in terms of historically bad laws passed.

1. The 5th United States Congress

In 1798, the United States was in an undeclared war with France. France was seizing American ships because the U.S. had been too cozy with France’s enemy, Great Britain, and because the U.S. had conveniently refused to repay the new Republican France the money it borrowed during the American Revolution (the U.S. claimed it owed the money to the old French monarchy, not the new French Republic). The President was John Adams, successor to George Washington, and not particularly popular. Adams’ Federalist Party was in control of Congress, and their solution to Adams’ personality issues was to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts. Purportedly passed to quell the threat from non-citizens in cahoots with France, the real political reason was to quell the threat from the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson, who sympathized with the French and who stood ready to defeat the Federalists in the next election.

The Alien and Sedition Acts not only made it harder to become an American citizen (14 years as opposed to the former five years), but allowed the government to arrest, imprison and/or deport any non-citizen who posed a “danger” to national security. More insidious, the Acts allowed the government to do the same to anyone, citizen or not, who spoke out against the federal government. This threatened to undo many of the freedoms the fledgling American republic stood for. Predictably, this did not serve to increase Adams’ popularity. He and the Federalists were defeated in the next election by Thomas Jefferson, and the Acts were allowed to expire. All that is, except for one of the acts, the Alien Enemies Act, which the U.S. still had in effect during World War II, and used to arrest, imprison and seize the property of Japanese, German and Italian citizens living in the U.S.

2. The 31st United States Congress

In 1850 the country was simmering with sectional conflict over the “peculiar institution,” slavery. Already the 31st Congress had passed the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California into the union as a free state, and allowed slavery in the Utah and New Mexico territories until its residents voted on the issue. The Compromise was yet another effort (the Missouri Compromise of 1820 being another one) to fend off the looming threat of succession and Civil War.

In September 1850, the Congress, in a capitulation to slavery advocates, passed the Fugitive Slave Act. This heinous legislation removed one of the few avenues escaped slaves had to gain their freedom. Prior to this Act, if a slave could escape to a free state or territory, he or she might have had hope of protection. Free states could claim that slave state laws did not apply in free states, and that slaves were people, not property. The Fugitive Slave Act changed that. Under the law, special commissioners were appointed to enforce the Act. Escaped slaves could not testify in their own behalf, and there was no jury trial to decide their fate. Commissioners were paid for each decision rendered, and remarkably, they were paid twice as much if they rendered a decision in favor of the slave owner ($10 vs. $5). Penalties were imposed on any marshals who refused to follow the Act, as well as anyone who aided in helping slaves escape. Bounties were paid to anyone who captured and returned a slave to his or her owner. Predictably, the Fugitive Slave Act created an uproar in free states, and resulted in more and louder abolitionists. Free states passed laws attempting to overrule the Act. The Underground Railroad grew larger and more efficient. All this ultimately led to the Civil War everyone wanted to avoid.

3. The 88th United States Congress

The 88th Congress must have had a devil on one shoulder and an angel on the other. Under their watch, we saw the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as historic a piece of legislation as ever became law, ending discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, as well as ending racial segregation in schools and other public facilities, Jim Crow and voting discrimination. On the other hand, it passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

On Aug. 2, 1964, the USS Maddox was engaged in illegal surveillance in North Vietnamese waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. The warship was fired upon by North Vietnamese torpedo boats (they missed). Two days later, the Maddoxreported being attacked again, although North Vietnam denied it, and an investigation in 2005 concluded that there was no attack. Nevertheless, in response to the phantom attack, President Lyndon Johnson ordered air strikes against North Vietnam. He requested a resolution from Congress, "expressing the unity and determination of the United States in supporting freedom and in protecting peace in southeast Asia," and giving support for, "for all necessary action to protect our Armed Forces."

On August 10, after only a few hours of debate on the issue, the 88th Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving LBJ the authority to wage war unilaterally, without the approval of Congress. In other words, Congress literally gave up the powers it had under the Constitution to declare war, and ceded them to the President. Thus began the expansion of the Vietnam War and the subsequent deaths of tens of thousands of American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians. Though repealed in 1971, the resolution provided the precedent that has allowed our oresidents to wage American military wars not expressly declared by the Congress.

4. The 66th Congress of the United States

They didn’t call them the Roaring Twenties for nothing. The decade was loud, lawless and theoretically dry, thanks to the 66th Congress and the passage of the Volstead Act, also known as Prohibition. Temperance societies had been around for 100 years, but by 1900 they began to grow in strength. They clamored for the end of alcohol consumption, blaming booze for many of society's ills and aiming to improve the moral character of the country. By 1919, many states had passed bans on the production and consumption of liquor, and the United States 66th Congress followed suit with the Volstead Act, making Prohibition the law of the land. President Woodrow Wilson actually vetoed the legislation, but the 66th overrode his veto and ensured its place among terrible Congresses.

In the beginning, Prohibition seemed to work, as bars shut down, drunkenness abated and advocates crowed about improving morality. However, sensing an opportunity, criminal elements soon began filling the vacuum and organized crime was born. Much as today’s “war on drugs” has spawned overcrowded prisons and unspeakable gang violence, the Volstead Act’s war on liquor spawned a proliferation of bootleggers, violence and legendary outlaws like Al Capone. The federal government was overwhelmed by the abundance of lawbreakers and the dearth of enforcement agents. In 1933, the Congress finally cried uncle and repealed Prohibition.

5. The 21st Congress of the United States

They were known as the Five Civilized Tribes. The Chickasaw, Seminole, Cherokee, Muscogee-Creek, and Choctaw Indian tribes had established Native American nations on lands east of the Mississippi River in the southeast United States. Sadly for them, the states they were settled in coveted the land the Indians lived on. Additionally, President Andrew Jackson was a noted Indian hater who supported removing the tribes. The political result was the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which dictated the removal of the tribes from their lands, state seizure of their property and their relocation to territory west of the Mississippi River.

“What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms?” wrote President Jackson at the time. Some voices in Congress (Davey Crockett among them) spoke out against the Act, as did Christian missionaries and others, but over the next several years, the removal was implemented anyway. Most shamefully, the Cherokees were sent west over the Trail of Tears, a forced march in which thousands of them died from disease and exposure. The Seminole tribe resisted, waging guerrilla warfare against the U.S. Thousands were killed during the years-long war, but ultimately the tribe prevailed and gained the right to stay in their native Florida lands.

Shares