On a bright Sunday in October, an acquaintance from a nearby town called to ask whether he was welcome to stop by with people from his church so they could put their hands on my wife and pray for her. Margaret responded that God knew enough of her without people reporting to Him about her contours, but our acquaintance persisted by warning that the devil causes human suffering and that healing can occur only when the Lord has been properly beseeched. “No thanks,” she said. “Though maybe if God Himself ever wants to put His hands on me, I’ll be in the mood.”

When they involve no touching of her by strangers, Margaret welcomes prayers. Yet usually such offerings cause me to think about unanswered prayers; for example, the millions of urgent prayers of intercession for the people trapped on upper floors of the burning Twin Towers. A former co-worker contacted me to say she had heard about my wife’s misfortune and was praying for her, but happily acknowledged the earthly limits of prayer: should the cancer prove fatal, God will have shown “He loves Margaret so much He wants her near Him in Heaven.”

Margaret says that by praying for her health, people are sharing love. I once wondered aloud whether people pray for her in part because any of them could fall mortally ill at any moment and they need to comfort themselves with the belief that prayers can cure what doctors cannot. Margaret asked, “And who loves purely? Are you telling me you do?”

In his famous commencement address at Kenyon College, David Foster Wallace reminded his listeners that everyone worships something. I think of his reminder when I am in a pharmacy and observe customers fingering bottles of vitamins and herbs as if they are rosary beads. I think of it as I cross the parking lot of my local YMCA and look up to see the sweating, huffing people beyond the glass front of the second floor as they pedal stationary bikes devotedly, fervently. When someone advises Margaret to give up sugar or avoid cellphone radiation or to drink green tea or eat more broccoli, I am reminded of the acquaintance whose church members desire to drive satanic cancer from my wife and instill salvation. A different acquaintance is sure that stress causes cancer. To protect me from stress-induced cancer, Margaret has assured me repeatedly: “They mean well.”

I too supposed the cause. Margaret grew up near a large commercial orchard and both of her parents smoked tobacco. I thought I knew the answer when I asked one of her doctors whether childhood exposure to pesticides and secondhand smoke might have caused the malignancy. “We have no evidence that any of those chemicals cause her type of cancer,” he replied. “The cause is unknown.”

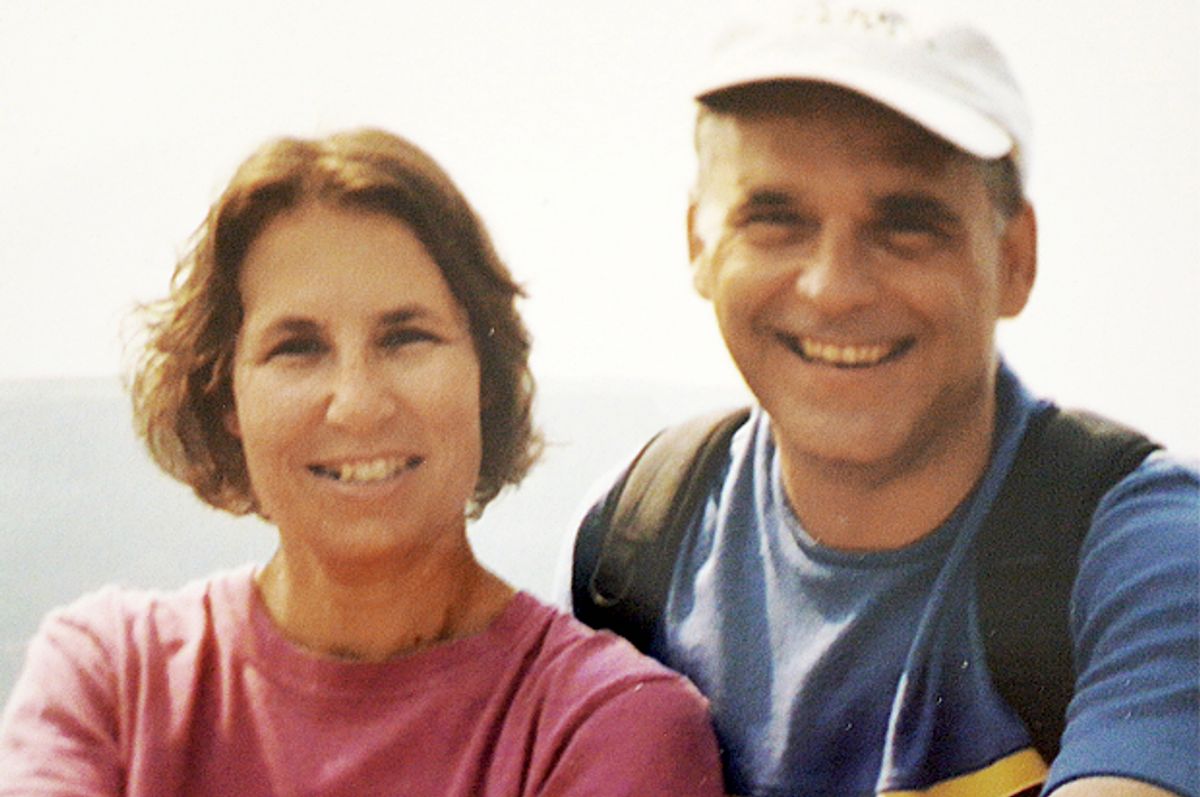

Margaret eventually permitted someone other than doctors and family to lay hands on her. Her sister had given her a wig and Margaret wanted it altered. The hairdresser explained that she needed to know whether it was made with natural or synthetic hair and would need to check the underside to be certain. Would Margaret like to go into the lavatory with her to remove the wig in more privacy? “Just take it off here,” said Margaret. While the hairdresser turned the wig inside out and examined it in the bright lighting, everyone in the salon could see the long purplish scar that began near one of Margaret’s ears and then slalomed over her head just inside the hairless hairline. Soon the wig was back in place and the hairdresser began her perfect trimming and styling of it. My wife and I live in the Alleghenies, in hardscrabble logging and dairy country where any hairdresser finds it difficult to earn even a bare living from standing on her feet all day and applying her special skill, and yet, on this day, this hairdresser declined to accept payment.

Margaret insisted.

From the waiting area, I insisted.

“Oh no,” said the hairdresser, “absolutely not.” She took Margaret’s head gently in her hands. “There’s no charge.”

Shares