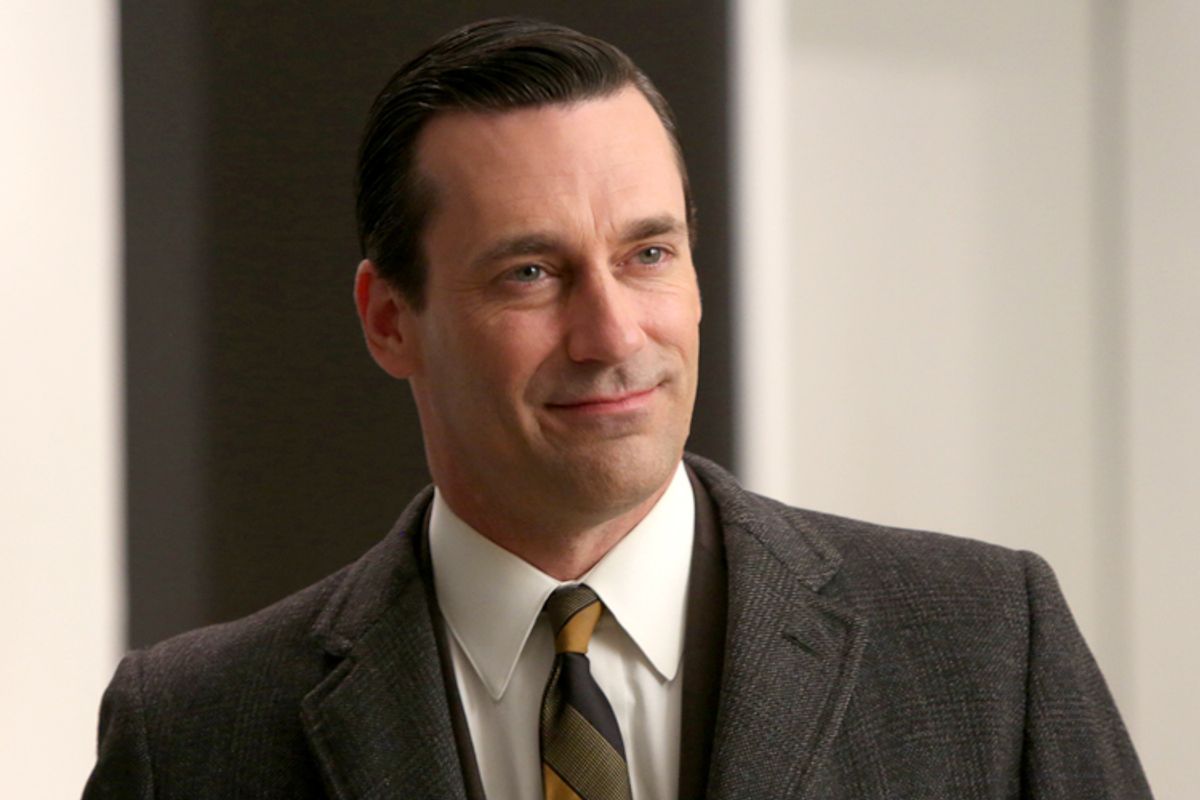

Perhaps it should have ended on that bench, with Don looking as if Hopper had painted Gump, detached and oddly contented, having just given the automobile he waited a week to have repaired to a young hustler, a former version of his conflicted self. I would have been cool with that, fading to black on a man about to dispense with the last 80-proof swig of his identity, if not his soul.

Or perhaps it should have ended one episode earlier. I might have been OK with each of our uniquely flawed protagonists balking at and ultimately rejecting joining the mega-agency McCann-Erickson. Joan cuts a deal she can almost live with. Don bails on his first gang bang of a meeting at the new place (though did he really need another gathering of empty suits to have the epiphany that this would never work?). I would have been fine ending on Roger playing the organ back at the abandoned offices of SC&P, drunkenly serenading the drunkenly roller-skating, partially liberated Peggy. Who knows what would have come next? Who cares? They were rejecting conformity and toasting a renegade existence. They had been on an eight-ish season voyage and, as Roger said, “It was a hell of a boat.”

I would have been OK seeing them all go down on that boat together.

But there’s more. There has to be. We hate the thought of final episodes for iconic shows but once the announcement is made we fetishize it and embrace it. We speculate and hope, demanding closure, fulfillment, answers, blood baths, reconciliation and perhaps (but hopefully not) some sort of maudlin montage. More.

I’m guessing that on Sunday night we will get none of that. Because “Mad Men” was never about plot in the traditional sense. I rarely left one episode anxiously wondering what happens next week. I usually sat scratching my head, wondering about the notion of family, capitalism, nostalgia, my own advertising existence and what it means to live a meaningful 21st century life. In fact, whenever plot became more about individual character rather than the crew of Roger’s “boat,” the show tilted toward sentimentality and familiarity. If anything, the protagonist that illuminated the most human of truths wasn’t human; it was the boat.

The two most popular Don be-gone theories are suicide and vanishing. It’s hard to ignore the suicide theory on a show whose opening credits depict a businessman plunging past the windows of a glass and steel canyon (not to mention, in Season 1 only, the accompaniment of a then-alive Amy Winehouse track). And over the years there have been so many suicidal teases. From visitations by the ghosts of Draper past (most recently Bert Cooper) to the longing/too long glimpse over the precipice of the high-rise he shared during his doomed relationship with Megan.

With Don it always seemed that the greater the height he achieved – in buildings, relationships and career -- the greater was the temptation to hurl himself from it. But rather than literally jump he has always chosen to slowly descend to a simpler (lower) place, than end it. Whether it’s the bottom of a bottle, the arms of a diner waitress or the Midwestern landscape of his youth. Rather than jump, I believe that Don will disappear even further from that bus stop, further shedding himself of altitude, responsibility and one identity while he waits for the next one to occur to him.

I used to think that, like many of the cable dramas that transformed TV, from “Oz” to “The Wire” to “Breaking Bad,” “Mad Men” was more of a visual novel than a mere TV series. I likened it to “Revolutionary Road,” Richard Yates’ classic borne of the “Mad Men” era. But “Revolutionary Road” had an ending. A tragic, heart-wrenching and definitive ending.

I don’t expect an ending Sunday night. Instead I expect a semi-confounding, semi-fulfilling hint of a beginning that will hopefully lead to Monday morning, universe-pondering head-scratching. Because “Mad Men” was never just a show, or like a novel. Like the carousel Don described to the Kodak folks in Season 2, it has no beginning or end.

Shares