The 1968 LP "The New Tweedy Bros!" is something of a perfect storm for serious record collectors. Being a local band on an unknown label with a minuscule initial run is good, for starters. They also happened to play a part in the genesis of San Francisco's exploding music scene. Sure, it was a minor part, opening for the likes of The Grateful Dead and Moby Grape... But hey – there they are on those amazing posters! Can't hurt.

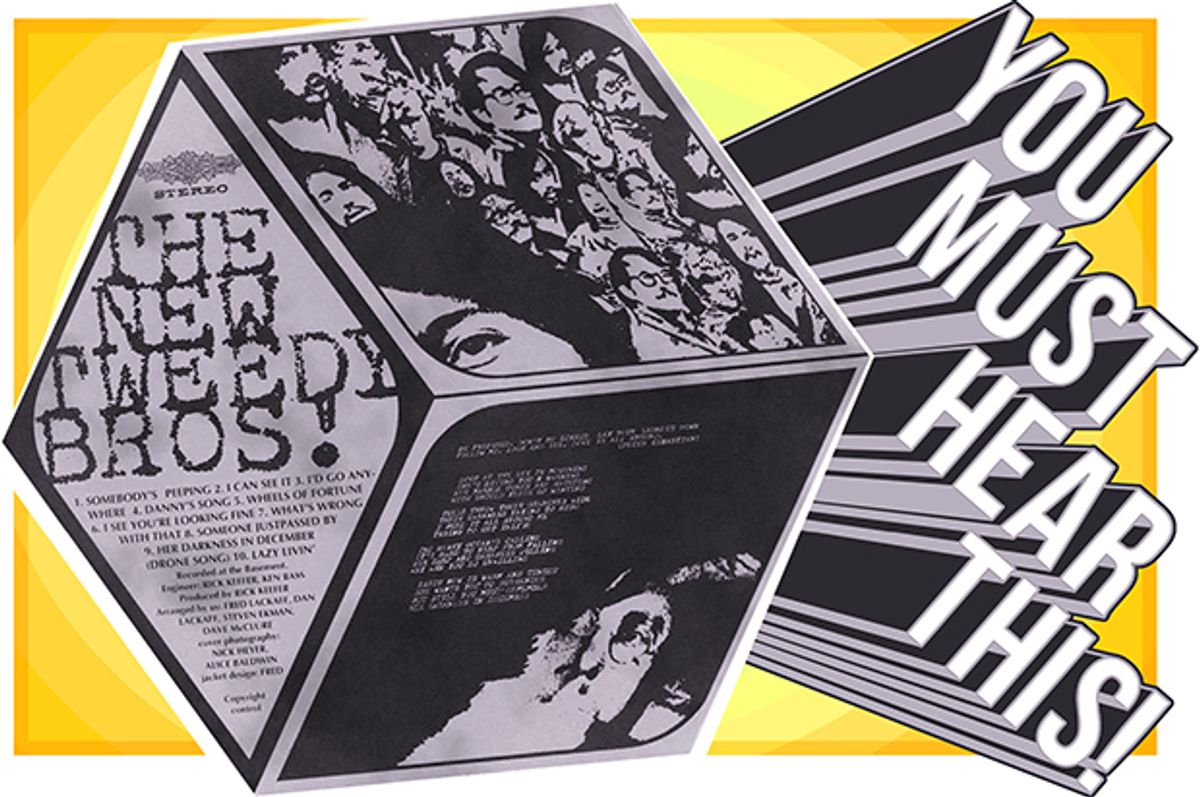

Add to this the fact that the record came out in a very cool but very unwieldy hexagonal sleeve – the kind that won't fit properly in record store bins – and you've got the makings of a so-called "Holy Grail" – a record that commands thousands of dollars if you can find one in mint condition.

Unlike a lot of the other Holy Grails I've seen out there, though, this one is very interesting and very good. It is very much a product of its time – a little shaggy, with its four-part harmonies, backward guitar, spoken word – even some autoharp, if I'm not mistaken. Listen to this, the first song, and see if it doesn't get stuck in your head for days:

I spoke with singer/guitarist Fred Lackaff on the phone. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you take us back to the beginning?

We were right on the heels of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones... Bob Dylan hadn't gone electric at that point. We had been basically folk singers and decided this looked a lot more exciting and glamorous – to be an electric band. But we still felt we were troubadours, very much a vocal group. And as it developed, we turned into more or less a dance band. The places that we played basically were dance halls.

That's surprising!

Yeah! Well it was surprising to us too, but it was kind of a pleasant surprise, because we found out it was really fun. That's where all the action was, everybody was going to the dance halls. There were light shows... drugs... it was a fun place to be. So that's where we gravitated.

We started out in Portland, where we all lived, and we acquired a manager who was a sandal maker, but he was from the Bay Area. He said, "I gotta get you down there, there's nothing happening in Portland." So he basically just rounded us up and drove us all down there, and we found a place to live.

When we first hit San Francisco, the first place we went to was the Avalon. We had a job there even before we got to town. Our manager had gone down and landed us on a show with The Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service. They just threw us in as a third band, which was common with those kind of jobs – there typically were two or three bands playing on any given evening. There was a lot of scrambling around, and they'd basically just leave the equipment up on the stage, and you'd just plug into whatever was there. So it was pretty loose.

What do you remember about playing with The Grateful Dead or Janis Joplin?

We were bumpkins! We came down from Portland, and we were the unknowns – none of us were that well-known at that point. Janis had just started singing with Big Brother, I think I might have seen the first time she sang with them – first or second time, anyway – at the Avalon. So, we'd all share the dressing rooms. There was just the usual camaraderie that musicians have. I can't say I developed any particular friendships with any of them, they were all nice. Everybody was just very loose about it. We were all just kids, enjoying the moment, pretty excited.

Does the album sound similar to what your live show would have sounded like?

About half the songs were pretty much the way we did them live. But we did experiment a lot – on "Wheels of Fortune" we did a lot of overdubbing, and building up of sounds... Part of the feeling was that people had heard all of our live material, the people that were going to be buying the album, and we really wanted to present them with something different than what we had been doing live. Whether we would have tried to do those things live later on, I don't know. We didn't stick together long enough to actually discover that.

We thought we were pretty cutting edge. They had just pretty much come out with eight-track machines, so we had that potential for overdubbing which, even when we had started a few years earlier, there hadn't been that potential, so this was pretty exciting. I can't say we really took it very far. We were all having fun.

I think that comes through.

I'm surprised that it's still as listenable as it is. Some of them are frankly pretty embarrassing, but I'm hardest of the two songs that I put on. "Her Darkness In December (Drone Song)" – I really wish we had spent more time on that, or developed that more. But we did that as a live number, it was one of our staples. And it usually was about fifteen or twenty minutes. It just lent itself to psychedelic rambling, a la Grateful Dead meandering. Depending on how creative we were feeling, we could stretch it out.

Was there a song that was a fan favorite?

We had so many, and we'd keep coming up with new ones... but yeah, "Somebody's Peepin" was a big favorite. When you played it live, it had that really strong bass – a really great dancing rhythm. It got people really moving.

The album has a really nice looseness to it. It feels to me like a band creating something completely on its own terms.

Definitely. There was nobody pushing us in any particular direction. There was no corporate entity trying to direct us in a certain way, it was self-produced. We had, ostensibly, a label that was something the guy that had the recording studio had made up. He basically gave us the studio time in trade for the rights to the material for a certain period.

We sold probably five hundred copies of the album in the year or two after it was released. We got a pressing made in L.A. and the smallest amount you could practically order was a thousand copies. The cover turned out to be so expensive to produce that we could only afford half of them at a time. (laughs) We went down to the print shop and the guy said, "I'll give you the rest when you bring the money in for the rest of it!" It was several months.

Was the hexagonal shape of it a logistical challenge for shipping and for the record stores?

Yeah, it was a big deterrent, actually, in terms of distribution. We never sent it out much beyond the Portland area. We might have sent a few copies down to San Francisco, we did sell some down there, but it was a pretty modest affair.

Of course, all of these factors are what make the album such a holy grail for record collectors.

Yeah, exactly. If you had an original cover now, an original album, it'd be worth several thousand. And I still have a few of those, but I'm not selling those any more. They're tucked away.

Did the band have a message of any sort?

No, we didn't have any agenda other than making people happy. We had a reputation for being a good-natured band, and most of our material was pretty upbeat. We tended to project that feeling, I think, on stage. Although, Steve didn't want us jabbering between songs – it was supposed to be cool. Introspective. A lot of bands had that feeling – you didn't have patter between songs. It was just not cool.

You describe yourselves as a good-time dance band, but I also sense an underlying anxiety. Almost an eeriness.

It could be. Every group has that experience where the material comes from the individuals in the group. And I think some of us had a darker... I don't want to say a pessimism, but they were much more into the drug scene, and didn't have a lot of faith in the future of our country or our culture. I think the album reflected more of that element than our live performances – we felt we were maturing and we needed to actually say something a little more serious.

What was the process – one of you would write a song, and bring it in and then you would all work it out together?

We weren't very inventive, in terms of arrangements.

Well, the harmonies certainly were, I would say...

Yeah. The harmonies were. The original name of the band was The New Tweedy Brothers Vocal & Instrumental Band, and we were strongly interested in the group vocals. Because we all sang – we were instrumentalists very much secondly! (laughs) I could barely play. I mean, I could strum a guitar. And none of us could play drums. Dan got voted the drummer because he sat down and he was the only one that actually could make them work. He wasn't happy about it!

So, the arrangements were pretty simple. We did develop them as a group. Once the song came to the group, we pretty much did it democratically, there wasn't anybody in charge of deciding the sound.

The whole album thing was pretty much my idea. I was determined that we had to put something down. I pretty much singlehandedly created the cover. It was something we had talked about for several years, but I do think it might not have happened without the push from me.

I'm glad you did.

Yeah, I am too! We're still just a distant memory, but I think thanks to the album, at least we still have a presence. Probably three or four times a year, I'll get a call or an email from somebody in their twenties who has just come across the album or discovered the music and it just tickles me that fifty years later, people are still enjoying it.

Fred Lackaff resides in the Nehalem Valley of Oregon with his sweetheart Vivi Tallman, where he plays in two local bands, and is having an indecent amount of fun.

Previously:

Shares