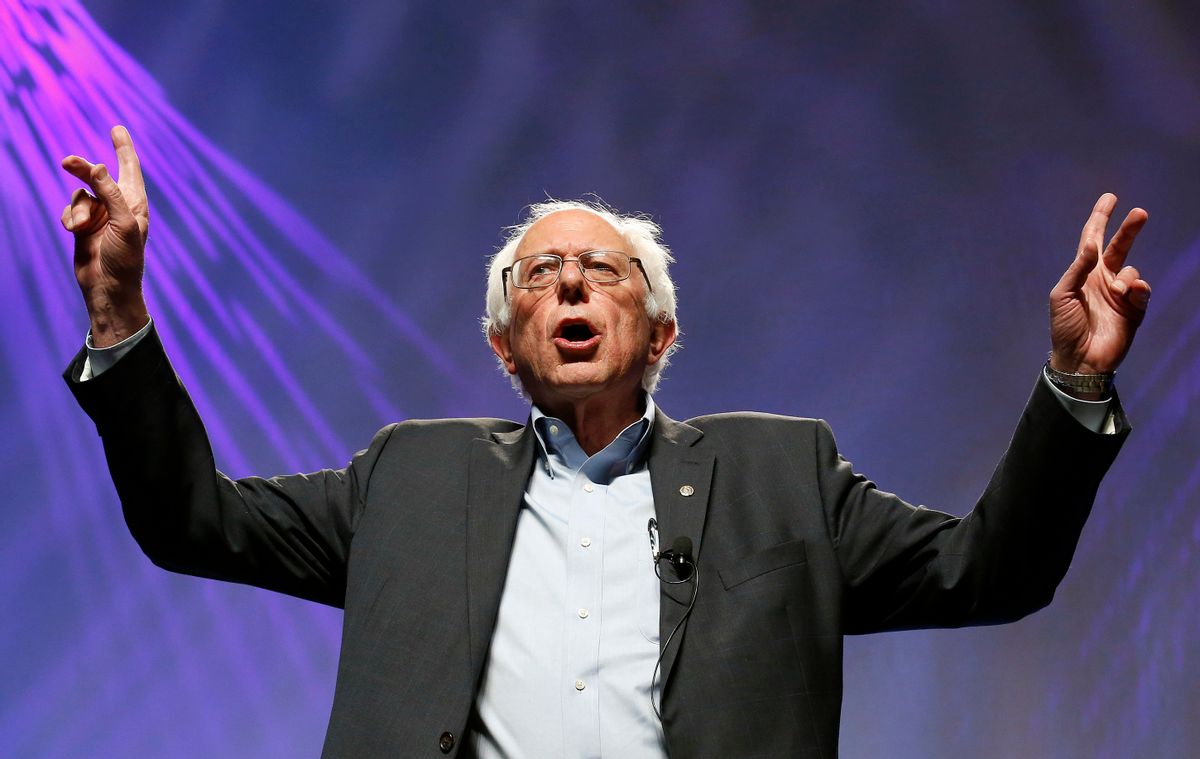

Bernie Sanders explicitly wants to start a political revolution in America. Judging from the crowd of 11,000 supporters in Phoenix on Saturday night, that has already taken place. Within a short period, Sanders has become the most electrifying presence on the 2016 campaign trail, attracting bigger crowds than any presidential candidate of either party. He has the grassroots army that he says is the critical component to progressive change. Now the question becomes what he will do with it, immediately, before any primary vote is cast.

After some unfortunate tone-deafness dealing with a protest from #BlackLivesMatter activists at Netroots Nation – something the campaign is already working to correct – Sanders rallied audiences in Phoenix, Houston and Dallas over the weekend. At the Phoenix Convention Center, the notably young crowd has gotten to know the democratic socialist’s positions so well (probably from his applause lines being tweeted on the campaign Twitter feed) that they repeated them in real time, like lip-synching at a concert. He has captured the imagination of a segment of the population who feels ill-served by the narrowness of our politics.

Among liberal millennials in their formative political years, Sanders offers truth-to-power rhetoric that speaks to the disappointments of the Obama years, on issues like Wall Street’s power, the takeover of government by the wealthy and the need for single-payer universal health care. Sanders’ path for sustaining real change is entirely based upon bottom-up organizing. “The key mistake of the Obama Administration,” Sanders said last year to Bloomberg, “was to more or less disband the grassroots network that he had put together to get elected.”

Now Sanders has that grassroots network, or at least a critical mass of people willing to listen to him on the issues of the day. There is no more prominent voice on the American political left today, save for Elizabeth Warren. And Sanders is arguably more visible right now, with news-making rallies and a growing email list (the campaign won’t say how big).

This gives Sanders an opportunity to show exactly what can happen when politicians use their popularity as an organizing tool. Because there are winnable fights happening right now that could use his attention.

For example, the federal highway trust fund faces a deadline at the end of the month, with plenty of potential downsides. The House passed a five-month patch setting up a more permanent fix that pays for infrastructure with a misguided tax amnesty for large corporations that park earnings overseas, which has been pushed in recent weeks by Chuck Schumer. Senate Republicans, thinking they may get a better deal with a colleague in the White House, are scrambling to find money for a two-year patch, including making significant cuts to the federal employee retirement program.

The payment options for infrastructure are pretty awful, compared to simply putting a user fee on the roads that need fixing through a small increase in the gas tax. Liberal Democrats have the power to shape what happens next, and the first stage of the endgame is happening in a matter of days. So where is Sanders on that? What’s he telling his supporters to do about it?

Tied up with the highway bill are negotiations around the expired Export-Import Bank. Though most of the Democratic Party now supports Ex-Im, in the past Sanders has been staunchly against it as an example of corporate welfare and outsourcing, earning praise even from the likes of Ted Cruz. Congress will try to resurrect Ex-Im soon. If Sanders still believes it helps ship jobs overseas, is he prepared to ask his new followers to help him stop it?

Similarly, within two months we will have a Congressional vote on the nuclear deal with Iran. Foreign policy items go completely unmentioned in Sanders’ speeches, but at his Senate website he called the deal “a victory for diplomacy over saber-rattling.” President Obama just needs one-third of either house of Congress to maintain the nuclear deal, again giving power to the liberal bloc. The votes will occur in September. Is Sanders prepared to organize around that?

There are more short-term issues up in the air, from the fight over the next appointment to the Securities and Exchange Commission to the inevitable battles over the government shutdown and raising the debt ceiling and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (which Sanders has already engaged on). What’s his strategy?

The model for organizing from inside the Senate comes from Elizabeth Warren, who uses her platform to push on short-term issues. She doesn’t always win, such as with the Citigroup-written derivatives loophole snuck into a federal spending bill last year. But she knows how to leverage her power and the citizens who believe in her message. She stopped Antonio Weiss from becoming the number three leader at the Treasury Department and has now apparently stopped Keir Gumbs, a lawyer who actually held seminars with corporations about how to evade taxes, from joining the SEC.

Warren derives her success from picking winnable fights and forcing fellow Democrats to take her side, because of the promise of being aligned with the emergent Warren wing. She is respected on financial reform and issues affecting the working class, and when she speaks up, it matters and can change policy.

Sanders has never had this platform for his issues before. But one email to his list (which he reportedly writes himself) or the mention of a particular topic on the stump could have significant organizing value. He has nationwide house parties coming up next week, over 1,500 of them, where he could spread a particular message, if he chooses. Tell Chuck Schumer not to give multinational corporations a bailout. Tell Democrats not to undermine diplomacy. Tell the President that prime regulatory seats should not be sold to Wall Street executives. And then he can supplement that with phone calls and protests. There’s an opportunity to operationalize his candidacy.

Making change is about more than giving a well-worn political speech. It’s about active engagement, challenging bad ideas pushed by powerful people and demanding something different. Sanders knows this: it’s the entire basis for his candidacy. But he could put it to work before anyone goes to a caucus in Iowa or a voting booth in New Hampshire. Things are happening right now that will impact millions of Americans. If Sanders is making the argument that he will be an organizer as President, he has to show that he can be one as a candidate, too.

Shares