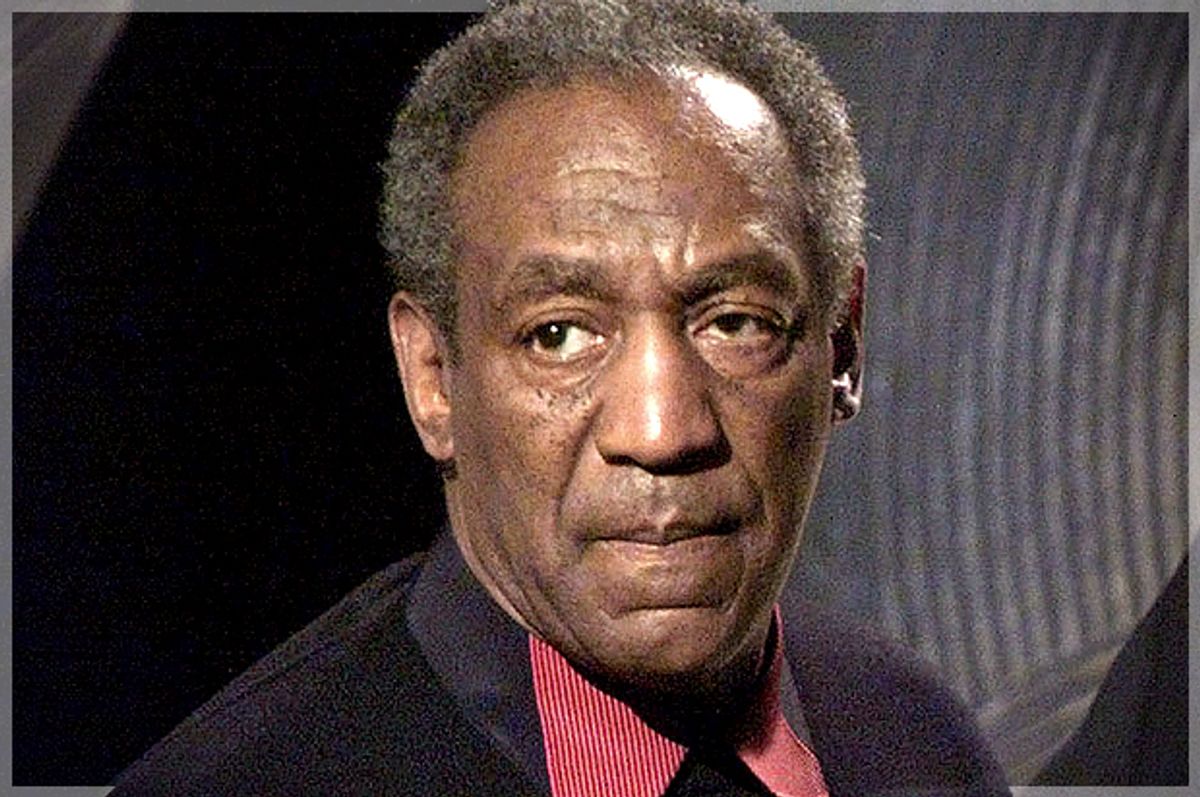

It’s becoming clear that this summer will go down as the one where Americans finally had a reckoning not just with the present problem of sexual violence, but with the past. The Associated Press finally dug up what many considered the smoking gun in the Bill Cosby rape saga, an admission from the man that he had procured sedatives to give women, which aligns with the more than 40 reports of sexual assault women have come forward in recent years to share. Then the Huffington Post published a disturbing account from Runaways bassist Jackie Fuchs where she recounted being raped by her manager Kim Fowley in front of multiple witnesses when she was a teenager in the '70s. Now the oldest story of all has come out: BuzzFeed has published a story detailing how Loretta Young’s secret “love child” with Clark Gable was likely the product of rape.

It’s becoming clear that this summer will go down as the one where Americans finally had a reckoning not just with the present problem of sexual violence, but with the past. The Associated Press finally dug up what many considered the smoking gun in the Bill Cosby rape saga, an admission from the man that he had procured sedatives to give women, which aligns with the more than 40 reports of sexual assault women have come forward in recent years to share. Then the Huffington Post published a disturbing account from Runaways bassist Jackie Fuchs where she recounted being raped by her manager Kim Fowley in front of multiple witnesses when she was a teenager in the '70s. Now the oldest story of all has come out: BuzzFeed has published a story detailing how Loretta Young’s secret “love child” with Clark Gable was likely the product of rape.

The question a lot of people are asking is, why now? These rapes happened decades ago — in the case of Gable’s alleged rape of Young, a full 80 years ago — so why is it all rushing out in a big, upsetting mess now? Conservatives, in particular, are focusing on this question, implying in some cases, as with Project 21’s defense of Cosby, that this passage of time should somehow cast doubt on the validity of the accusations.

But, if you take a step back, it’s easy to see why this is all coming out now. As Fuchs explained to the Huffington Post, she was inspired in large part by the current movement on campuses to expose and combat campus rape. “They have to be making the same value judgments about themselves as I made about me,” she said.

Many Cosby accusers have said similar things. “Over the years I’ve met other women who also claim to have been violated by Cosby. Many are still afraid to speak up,” Beverly Johnson explained in Vanity Fair. “I couldn’t sit back and watch the other women be vilified and shamed for something I knew was true.”

But there’s another, darker aspect to all of this: One reason these stories are coming out now is because, at the time, the culture just didn’t have the language or understanding to really grapple honestly with what happened. As Anne Helen Petersen writes in her piece about Gable and Young in BuzzFeed, there were “millions of unwanted sexual encounters that entire generations of women did not talk about” because the culture did not understand them as “rape.” It was seen as something more ambiguous.

What’s really changed in the past few years is that we’ve reached a cultural consensus that all non-consensual sex is rape, after literally decades of feminists working on this issue. It’s not “gray rape” or even “date rape” anymore; rape is just called rape. No matter who does it or under what circumstances, it’s the same crime, just as surely as assault is assault whether you hit a stranger or a friend.

Even the rape apologists have largely conceded this point. While some rape apologists still cling to the illusion that you can force someone to have sex while somehow not raping them, most these days have shifted tactics. In some cases, they accuse victims of making it up or lying about not consenting when they did. In some cases, they accuse feminists of exaggerating the problem for vague power-and-money purposes. Or they will pretend that due process is being abandoned when it comes to rape accusations. Or they might try to argue that feminists are somehow demanding impossibly high levels of consent in order for sex to happen. But less and less often will you see someone try to argue that overcoming a woman’s resistance is normal or romantic or anything other than what it is: Rape. And those who do, like George Will, are largely being excoriated.

It’s important to remember that it wasn’t always this way. Forcing oneself on a woman has never been considered gentlemanly behavior, to be clear, but it was often just not called rape. As recently as the '80s, date rape was portrayed in movies not as rape, but as boys and men “taking advantage.” "Revenge of the Nerds," "Sixteen Candles" and "Meatballs" all portray young men raping women as little more than just aggressive flirting, suggesting that women either don’t mind or even like being forced.

The idea that it’s always rape to force sex on an unwilling person was considered controversial even in the '90s. Katie Roiphe built her early career arguing, to much acclaim, that it’s not really rape to force yourself on an unwilling woman. After reading in 1993 that researcher Mary Koss defined it as rape to have sex with a woman who “didn’t want to” after she was incapacitated by drugs or alcohol, Roiphe scoffed, “Why aren't college women responsible for their own intake of alcohol or drugs?” In these circumstances, Roiphe claimed, “it isn't necessarily always the man's fault” to have sex with someone with someone who doesn’t consent.

The reaction to the Cosby story shows how much the world has changed in the past two decades. Very few people are trotting out the Roiphe argument that it’s only really rape if there are “bruises and knives, threats of death or violence.” That it’s rape to force sex on the unwilling, every single time, is just understood to be true now. The best they can do is what Christine Flowers of Philly.com did, which is to try to argue weakly that maybe the women in question willingly took the drugs to have consensual sex on them. But even she must admit now that it is rape, really and truly, to take advantage of an incapacitated woman.

This shift toward cultural consensus that all forced sex, in every circumstance, is rape, is an extremely important one. As Jackie Fuchs’ story makes clear, just because the culture around you refused to call it rape doesn’t mean it wasn’t rape. While it’s impossible to get in the heads of the people who witnessed Fowley raping Fuchs, it’s not hard to imagine one reason they didn’t intervene — and that some witnesses reportedly made fun of her after— was that they just saw it as “taking advantage” of a drunk girl instead of rape. But her trauma that led to her breakdown and quitting music was still the reaction of a rape victim, even if that word wasn’t as commonly employed to describe her experience then.

It seems the same lesson can be drawn from Loretta Young’s situation. Young’s family claims she didn’t really understand that being forced to have sex was rape until 1998, when she heard the phrase “date rape” and realized that was what had happened to her. Calling it what it actually was, they claim, was an immense relief for Young. “We talked about it, and it didn’t make her angry at him, it just gave her a new frame that I think lifted a lot of her guilt,” Linda Lewis, Young’s daughter-in-law, said. Until then, Young had carried around guilt from a culture that blamed victims, even denied that they were actually victims, for supposedly tempting their rapists.

It’s important to remember, as these stories come out, how dramatically the culture has shifted around this issue. Not to excuse those who committed rapes — as the Cosby stories make clear, they knew very well what they were doing was wrong — but to understand why victims often didn’t come forward in the past. Right now, so many rape victims are coming forward that it seems overwhelming, leading some to argue that there can’t really be that many rape victims and that it’s just a product of some kind of mass hysteria.

But it’s not that there are more rape victims than ever before. In fact, there are probably a lot fewer. It’s just that we aren’t accidentally hiding millions of rape victims by calling their experiences “bad sex” or “taken advantage of” or “ungentlemanly behavior.” Now all the rapes are being counted, not just the few that happen under the most extreme circumstances. And now that we have a real understanding of the problem, we can finally take real steps to combat it.

Amanda Marcotte co-writes the blog Pandagon. She is the author of "It's a Jungle Out There: The Feminist Survival Guide to Politically Inhospitable Environments."

Shares