"We're making decisions just based on the money.” That’s Rosemarie Jensen talking, a tone of exasperation creeping into her voice as she describes the influence of money on education policy in South Florida. “Some things should be run like a business," she tells me in a coffee shop near Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “Education isn't one of those things."

"We're making decisions just based on the money.” That’s Rosemarie Jensen talking, a tone of exasperation creeping into her voice as she describes the influence of money on education policy in South Florida. “Some things should be run like a business," she tells me in a coffee shop near Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “Education isn't one of those things."

Jensen lives in Broward County, just to the north of Miami-Dade. Broward is home to a diverse population of students, drawn from the state's most exclusive gated communities as well as neighborhoods wracked by generational poverty. A former K-1 school teacher and current public school parent, Jensen is part of a growing movement of parents who believe they are being shut out of important decisions about public school governance, while those making the decisions too often have something monetary to gain.

As a leader of United Opt Out, an organization that advocates boycotting standardized tests in public schools, Jensen has opted her own son, a special education student in high school, out of the Florida state exam now known as the Florida Standards Assessments. But standardized testing isn't the only thing that's got her steamed.

Jensen recounts stories of her father, a first-generation immigrant and high school dropout, who cleaned out tankers so he could raise his daughter in a neighborhood with good public schools and eventually send her to college. Today, she sees that idealistic view of the American dream being undone in her community by an invasion of moneyed interests promoting charter schools.

In her view, charter schools — the privately managed, publicly funded entities that operate outside the oversight of democratically governed school systems — are not now what they originally claimed to be: centers of innovation created by teachers and parents. Jensen has taken note of the amount of money these schools spend on advertising and marketing. She complains that the middle school her children attended can't get money to construct a safer point of entry, while the state steers funds to charters for new construction. She believes that making public schools compete with charter schools for money dilutes funding that should be paying for better education for all kids. While she used to be open-minded about these schools, she now considers herself to be “anti-charter."

She’s not alone. Charter schools may continue to enjoy generally favorable ratings in national surveys of Americans, but many parents and public officials across South Florida, where these schools are now more prevalent than in other parts of the country, openly complain about an education "innovation" that seems more and more like an unsavory business venture.

Undermining Public Education

The obsession over money that is driving charter school growth in Florida is increasingly evident to those who bother to look.

"Outrageous," is the word former state Senator Nan Rich uses to describe recent decisions Florida lawmakers made to steer more money toward these schools. Until she termed out, Rich represented the 34th District that overlaps part of Broward County. Although she has never opposed charter schools, she now believes financial demands coming from the sector have become unreasonable.

As a recent article in Florida’s Herald-Tribune notes, for the past two years, only charter schools have received capital outlay funds from the state for new construction. Now charter school lobbyists say their schools deserve a share of local property taxes too.

"When they were started, charters were never supposed to tap capital funds," Rich explains, "but gradually lawmakers with ties to the charter industry tipped the scales to favor them financially."

"I'm not one who opposes charter schools that are set up the way they were intended," Rich adds. But she now believes, "The whole movement…is undermining public education and moves public money to private interests."

What Rich and Jensen describe is an increasing fear among parents and public officials across South Florida — and Broward County in particular — that any educational value charter schools were supposed to bring to the state is now overshadowed by corruption and chaos linked to money-making.

A new consensus is percolating from the ground up that those responsible for starting and operating charter schools, and making decisions to support the growth of these schools, "don't understand children,” as Jensen puts it. They’re mostly, "motivated by money.”

So how did this happen to Florida, and to Broward, specifically?

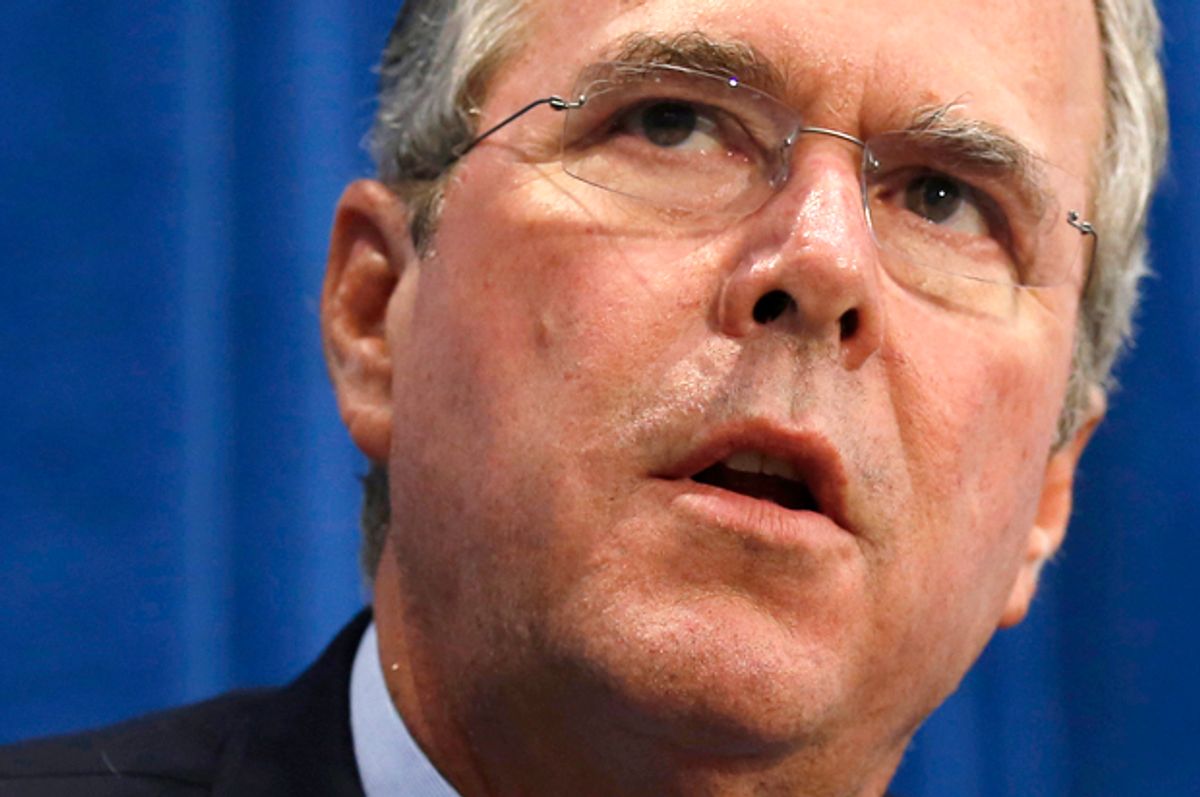

Jeb Bush and the Charter School Business Model

Most people trace the manic scramble for more charter schools in Florida to one source: former governor and current Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush. In 1996, two years before he became governor, Bush helped steer passage of the state's first law permitting charter schools. That same year, he led the effort to open the state's first charter, Liberty City Charter School in Miami.

During Bush's first administration, charter school growth averaged a whopping 56 percent annually in the Sunshine State, according to a Florida-focused NPR outlet. Annual growth rates during his second and final four-year term dropped to 17 percent, but by the time Bush left office in 2007, charter schools across the state had grown from a modest 30 in total to well over 300. The number of Florida charter schools has since doubled to over 600.

In his initial campaign to promote these schools, Bush maintained that charter schools would rescue students from supposedly failed public schools, especially in low-income communities of color. But by 2009 — two years after he left office — Bush’s rationale for charter schools had significantly changed.

According to a Palm Beach Post news article published that year, Bush debuted his revamped message at a summit put on by his non-profit organization, the Foundation for Excellence in Education, in Washington D.C. In his speech to that group, he declared, “I wish our schools could be more like milk.…Go down the aisle of nearly any major supermarket these days and you will find an incredible selection of milk…They even make milk for people who can’t drink milk."

Bush would repeat his observation from the dairy aisle three years later at the Republican National Convention of 2012, and what was once thought of as a civil rights cause became firmly established as a campaign for a new business-oriented model that would offer increased consumer “choice.”

“It started as a movement and now it’s an industry," Vickie Marble, a well-known Florida charter school advocate, gleefully declared to NPR reporters chronicling the evolving messaging campaign.

Jeb Bush was not the only one touting charter schools. The same year he made his pitch to the RNC, an investment consultant enthused on CNBC that charter schools were "a great opportunity… a half billion dollar opportunity.” In short order, news outlets from Forbes to the Huffington Post reported the growing interest among investors in charter schools and the lucrative opportunities resulting from this new model. And the cultivation of that interest continues: in March of this year, Business Insider reported that the "Walton Family Foundation — the philanthropic group run by the Walmart family — sponsored a symposium at the Harvard Club for investors interested in the charter school sector."

Aided by influencers like the Waltons and others, Jeb Bush put South Florida squarely at the forefront of the charter school bonanza. And the rise of the charters as big business in Florida brought with it new and special forms of financial corruption.

Innovative Education or Corrupt Business Model?

When Bush announced his presidential campaign earlier this year, a reporter from BuzzFeed noticed that many of his campaign videos feature the candidate in classrooms filled with happy schoolchildren — but not just any old classrooms. "Almost all of the classrooms have something in common,” reporter Molly Hensley-Clancy wrote. “They are at schools operated by Academica, [Florida’s] largest for-profit charter school management company."

With nearly 100 schools in Florida "and well over $150 million in annual revenue," Academica has been a key player in charter school expansions in the state since 1999. And Bush has shown an affinity for the schools for years. "As governor,” Hensley-Clancy reports, “Bush visited Academica schools several times, his emails show.”

But Academica has a long history of financial wheeling and dealing, so much so the organization is now the target of "an ongoing federal probe into its real estate dealings," as the Miami Herald reported in 2014. While the 1996 law allowing charters to operate in Florida restricted applicants to nonprofit groups only, profit-minded charter businesses like Academica have skirted that restriction. A report written by Patricia W. Hall for the Florida League of Women Voters explains how the scheme works:

"Although charter schools must, by Florida law, be overseen by a non-profit board of directors, there are many ways in which for-profit organizations have begun to highjack the charter school movement. For-profit management companies frequently provide everything from back office operations including payroll, contracting with vendors for food services, textbook, etc., to hiring principals and teachers and curriculum control."

Hall goes on to explain how real estate deals have become another form of profit-making in the Florida charter school business model. According to Hall, for-profit management companies such as Academica that manage charter schools receive "a variety of grants, loans and tax credits for building a charter school." Then they can charge the school district exorbitant rents and leases for the use of the building. This results in an "ever escalating" revenue stream of taxpayer dollars flowing to the charter school management company. Should the charter management company decide to eventually sell the building to another entity, it "reaps the profits," Hall writes.

These sorts of charter school-related real estate schemes led to a firestorm of land deals in Florida during the Bush years, according to an investigation by Alec MacGillis in the New Yorker. "Developers of new subdivisions teamed up with companies that were opening up charter schools less as a means to innovate than as a way to benefit from Florida’s boom,” MacGillis writes.

By 2011, charter school chains like Academica were getting so fabulously wealthy they drew the attention of an investigative report from the Miami Herald. Reporters Kathleen McGrory and Scott Hiaasen found 15 years of steady growth had turned Academica into "Florida’s largest and richest for-profit charter school management company, and one of the largest in the country." The reporters found the charter school chain practiced a "business strategy repeated across Miami-Dade and Broward Counties." Through these complex real estate arrangements, Academica founders Fernando and Ignacio Zulueta — brothers who were former real estate developers — had built, by 2010, a portfolio of 20 land companies generating millions of dollars.

Shady Land Deals

Another large, Florida-based, for-profit charter school chain, Charter Schools USA, practices a similar business scheme. As a Florida television outlet reported in 2014, "Charter Schools USA makes millions by managing schools, but tens of millions building and renting their buildings."

The reporters note that when a non-profit board opens a new charter school and contracts with Charter Schools USA to manage it, Charter Schools USA's for-profit "development arm, Red Apple Development, acquires land and constructs a school. Then, CUSA charges the school high rent.” One charter school paid “a $2 million rent payment to CUSA/Red Apple Development. The payment will equate to approximately 23 percent of its budget.”

Academica and Charter Schools USA are hardly the only large charter chains operating under these kinds of business practices in Florida and generating significant growth as a result. According to Hall's research, "The top four charter operators in Florida for 2011-2012 were Academica (72), Charter Schools USA (37), Charter School Associates (20), and Imagine Schools (23).”More recent research by Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker finds that large charter school chains — the ones mentioned by Hall, as well as others like White Hat Management, Rader Group, the Richard Milburn Academy and KIPP — dominate the state.

As governor, then later as the head of his influential foundation, Jeb Bush did everything he could to facilitate these sorts of charter school business dealings. As MacGillis explains in his piece for the New Yorker, "Bush signed a law allowing charter operators who were denied approval by local school boards to appeal to the state." The "state," in this case means the Florida State Board of Education, which was appointed by, you guessed it, Gov. Bush.

According to MacGillis, Bush also "signed a law to eliminate the state’s cap on the number of charters" and joined in the fight "to increase the amount of taxpayer money available for charter construction, and to let developers build schools using the subdivision homeowner fees that they used for pools and other amenities."

There’s no doubt Bush's ties to the charter industry will stay strong during his presidential run. When he formally announced his 2016 presidential bid in June, John Hage — founder of Charter Schools USA and a former Bush policy analyst — was by his side, according to the Miami Herald. "Before the speech," the reporter notes, "Bush gathered about 200 'alumni' — longtime supporters, former aides and friends — to thank them and ‘get his crying out of the way.’” Hage was one of the chosen few; it was he who was quoted by the Herald.

The Charter Invasion of Broward County

From the outset, Broward was a central target in the charter industrialists’ plans to take over Florida’s schools. Armed with messages about consumer choice, charter operators quickly capitalized on the county where some of the state's highest real estate valuations and rental prices could be found.

“Broward County has nearly two million people who live in relatively small cities,” writes Sue Legg in a report for the Florida League of Women Voters. Ft. Lauderdale, Broward's largest city, is home to fewer than 200,000 people. But Broward County has lots of charters, Legg notes.

Of the approximately 310 schools in the district, more than one-third are charters, and charter school openings continue at a fast clip, with 19 new charters likely to open in the year ahead, says Legg,

"What's particularly odd is that all of these charters are opening in Broward at the same time that so many existing ones have recently closed, or are in danger of closing. As Legg explains and a report from a local news outlet confirms, 25 percent of the district’s charter schools, a total 23 schools, finished the 2013-2014 school year with a deficit, “ranging from a low of $4,591 to a high of $318,567.”

Indeed, as the number of charter schools in Broward has expanded, so has the number of charter school failings due to financial insolvency and poor academic performance. As the Sun Sentinel reports, of the recent 36 charter school closings in South Florida, 21 occurred in Broward.

One charter high school in Broward “shuttered hours before students were to report for class on the first day of school,” the article notes. Two other Broward charters shut down after two weeks because their shared building wasn't fully constructed.

And here’s the other significant problem with the charter schools in Broward: it’s never been clear that the citizens who live there actually asked for them.

Who Wants Charter Schools?

“Charter schools open up at will whether there’s a need for them or not,” explains Laurie Rich Levinson in an interview over the phone.

Levinson is a Broward school board representative and the daughter of former state senator Nan Rich. “We don’t get to decide who can open charter schools and where exactly they can open,” she explains. “Charters were supposed to be created to fill a gap… do things differently for a specific community of students. But at this point there’s no collaboration.”

Levinson complains about an onerous process from the state that requires local school districts to approve new charter school openings on very short notice. “We must approve them even when we don’t know where exactly they’ll be located,” she says.

Michael Ryan, mayor of the city of Sunrise, a Broward municipality, is another local official who is grappling with the impact of charters without seeing any strongly expressed need for the schools coming from his constituents. In his view, the original idea of charters was to open in neighborhoods where citizens felt the schools are not working. But “we’re not that type of community,” he tells me during a conversation in his office. “We love our schools.”

One of the clearest signs of the low demand for charter schools in Broward County can be found in the main reason these schools so often close: low enrollment. A 2014 report from South Florida-based Naples Daily News found that charter schools across the state frequently overestimate the potential demand for their services. Reporter Jacob Carpenter found that the 48 charter schools that opened in Florida in that year ended up enrolling just 54 percent of what they estimated they would enroll on their charter applications. A "conservative" estimate by the paper found that these schools missed their revenue projections by a total of "at least $35 million."

Carpenter highlights one school in particular, New Life Academy in Broward County, which opened up in a strip mall and attracted just 50 students — “less than one-tenth” of its projected enrollment. In the county’s official enrollment counts, taken in October of last year, the number of students served by New Life Academy in 2014-'15 was down to 37. Another Broward charter school, Avant Garde Academy, "ended up with 85 students…after planning for 750 children."

Carpenter also pointed to five recently closed Broward charter schools that enrolled as few as 18 students. Only one of the closed schools had over 100 students. And with a new school year just starting in Broward, there are already reports of charter schools being closed due to low enrollment.

Location, Location, Location

Despite this unproven demand, the drive for profit has kept the charter business booming, a fact many of the local officials in Broward, who have to deal with the human consequences of the expanding sector, find unsettling.

“They seem to go wherever they want,” Mayor Ryan says about charter schools, “even in areas zoned light industrial.”

The siting of charter schools recently prompted Ryan and the Sunrise commissioners to pass a one-year moratorium on the creation of new charter schools. Although the commissioners eventually approved the charter trying to locate in an industrial zone, Ryan and his colleagues continue to consider other ways to influence where and how these schools operate.

What often drives charter school locations, Ryan believes, is the need to be centrally located and accessible by car (“like a big box store,” he observes), because charter schools generally don’t have to provide their students with transportation. Also, because there is little demand for charter seats from local parents — who generally prefer to have their children attend traditional public schools — charter operators are especially prone to site their schools in places where they will draw attendance from outside the community. (Even when students who live in Sunrise do want to attend one of the new charters, state law prohibits them from getting preference over students coming from outside the community.)

All these factors governing charter school location seem to amount to a deliberate design to place schools on properties that have high real estate values to justify expensive construction and lease arrangements — and to ensure the properties will hold their real estate values over time.

“The business model these schools seem to follow,” Ryan observes, is clearly “site-driven as opposed to needs-driven,” which is the cause of more than just headaches for city administrators. It also potentially threatens the welfare and safety of the county’s children.

Are the Children Safe?

Unlike traditional public schools, charter schools can open their doors without having to adhere to traffic restrictions, building codes and other kinds of regulations that are required of most other businesses and institutions. “If you want to open a business in this community, you have to meet certain requirements,” Levinson observes. “But charter schools don’t have to do that.”

This absence of meaningful regulations on charter school building and operational guidelines has more than one Broward County official concerned. Children’s safety is what motivated Lauderhill mayor Richard Kaplan to take action to provide more regulation of charter schools. Kaplan sees charter school proliferation as a potential endangerment to the health, safety and welfare of Broward County's citizens.

“We have no problem with charter schools,” Kaplan explains in an interview in his office. “They're supposed to be less regulated from other forms of schools so they can do what they deem necessary for their students.” Nevertheless, Kaplan led Lauderhill in placing a moratorium on new charter school development even before Sunrise did, and then imposed restrictions on new charter schools that did open. Why?

"We have an obligation to ensure the school is a safe environment and the school has the capacity to provide certain requirements,” Kaplan says, and then ticks off a list of obligations any parent would agree they want schools to adhere to, including crossing guards, adequate entrances and exits, insurance, fire escape routes, background checks of employees, and the financial wherewithal to operate for a full year.

Kaplan shares harrowing accounts of charter school disregard for the safety of students, including picking locations at busy intersections with no crossing guards to protect students going to and from the school, and no traffic lanes for parents to wait in when picking up their children. According to Kaplan, at one charter school, a fire alarm went off and no one knew what to do because the school had no procedure for fires and had never conducted a fire drill.

“No one has been injured that I know of,” Kaplan explains, “but there could be a time when a kid is injured, and that's what I worry about.”

Kaplan also worries that people who oppose charter regulations of any kind will “run to their state legislator to have him step in.” He imagines that a pro-charter lawmaker might eventually propose a bill to prevent local authorities from regulating charter schools.

“But,” Kaplan says, “I find it hard to believe they'd convince others that we don’t have the authority to require things like crossing guards and fire escapes.”

The Real Cost: Undermining Public Schools

The damage inflicted by the spread of charters in Broward and elsewhere does not stop at the corrupt land deals and the mounting chaos in communities. The most dangerous element of their impact is that they seriously damage the financial viability of local public schools.

As early as 2011, it became apparent that the spread of charter schools in Broward and Miami-Dade was causing financial mayhem for local public schools. As an independent media source reported at the time, charter schools located in those districts were already "siphoning off $40-$50 million in state money."

"The loss of the funds comes at a time when both districts are facing financial difficulties due to state funding reductions caused by the continuing economic downturn,” another article from the same news source reports.

But it's not surprising that public schools struggle financially when competing charters open near them, given the prevailing financial model used to fund charters. As in most states where charter schools exist, Florida funnels state funding for charter schools through local school boards that ensure the charter school receives a proportion of operating funds based on the number of full-time students enrolled. Local public schools receive funds much in the same way. In this practice, where “the money follows the child,” as each child transfers to a charter, state funding is added to the charter and subtracted from the public school's state funding.

When a neighborhood school loses a percentage of students in a particular grade level or across grade levels to charters, the school can't simply proportionally cut its permanent costs for things like transportation and physical plant. It also can't cut the costs of grade-level teaching staff proportionally. That would increase class sizes enormously and leave the remaining students underserved. So instead, the school cuts a support service — a reading specialist, a special education teacher, a librarian, an art or music teacher — to offset the loss of funding. This damages the effectiveness of the neighborhood school long-term and causes it to slide further into the ranks of “low performing.”

The opening of charters isn't the only thing harming communities; their negative financial impact can actually worsen when they close. As a report from a South Florida news outlet found, local officials in Palm Beach County, just north of Broward, are "pursuing legal action against two [charter] schools that closed to try to get about $400,000 back. The schools either moved the funds or [they] had been frozen by lien holders."

In Broward, according to a recent Sun Sentinel report, "County schools may have to repay $1.8 million owed by two closed charter schools." Because a recent state audit found the charters didn't keep accurate counts of the number of students enrolled in the schools, money the closed schools already collected will be withheld from future payments to the district.

As state funding for local schools declines, counties like Broward have the option to raise property taxes and/or offer bond referendums (often called mill levies) to pay for increased operational and construction costs. But charter school advocates in Florida are lobbying to get a share of those funds as well.

Thus, the race to the bottom continues, confined to issues of money and finance, rather than debates about how to actually educate children.

A Movement Whose Mission Has Soured

It is worth noting that many of the individuals who led the creation of the charter school movement — including Ray Budde who introduced the idea and Albert Shanker who made the idea famous — ended up opposing it. These schools, which were originally conceived as laboratories that would experiment with education innovations, today seem to provide very little that is innovative. As a scroll through the current directory of Broward charter schools maintained by the state shows, charters in Broward County tend to practice a uniform method of teaching called direct instruction, a strict form of teacher-directed pedagogy that is far from new or groundbreaking.

Proponents of charter schools argue it's time to “move on; charter schools are here to stay.” Instead of questioning the actual need for charter schools, they want to see the discussion shift to issues of "choice" and "scalability," topics that are more germane to business and industry than to teaching and learning.

Critics of the charter school industry, like Rosemarie Jensen, have other questions they’d like answered. "When can we get our libraries and librarians back?" Jensen asks. "When can we get instruction in the arts and music back in schools?"

How would Jeb Bush answer that?

Shares