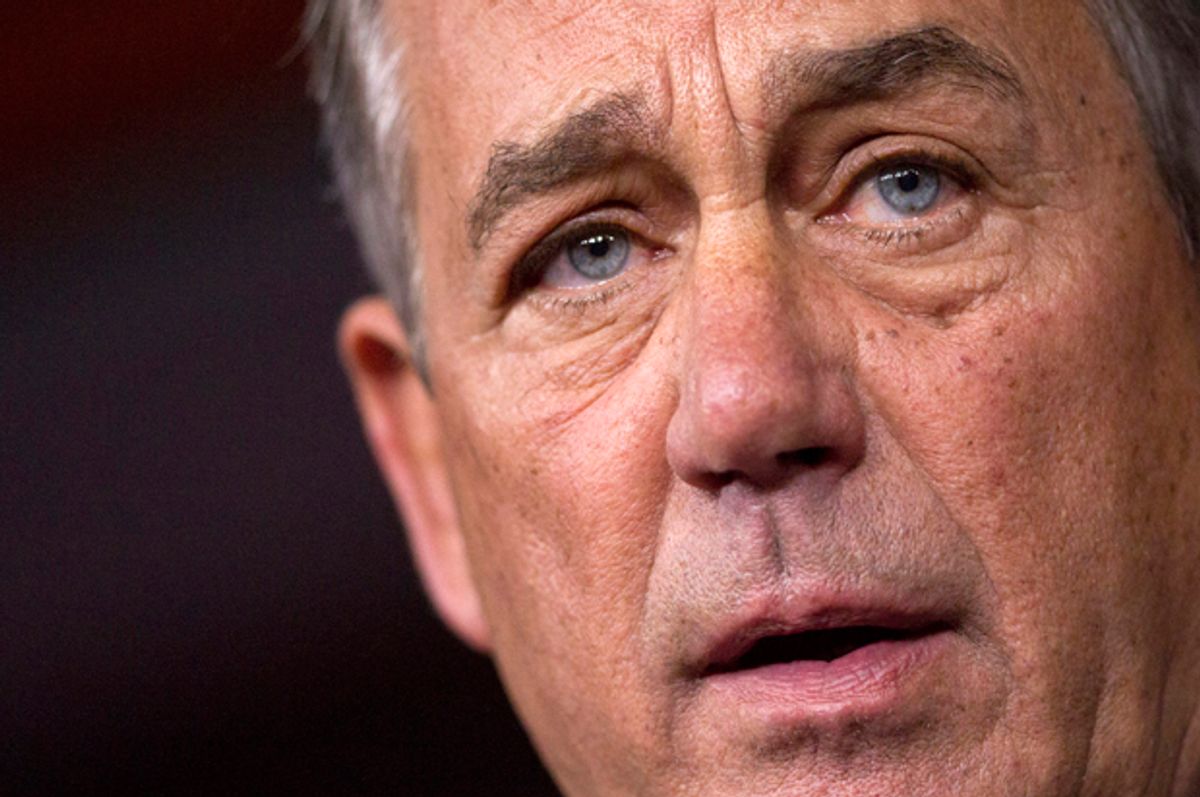

Earlier this week, staff from the office of Speaker of the House John Boehner and the White House announced that the two sides had come to an agreement on a budget deal that will fund the government and lift the debt ceiling until the early months of 2017. The news was greeted with surprise by most, and was welcomed by those within the American political class who pine for the good old days of Tip and the Gipper. National Journal’s Ron Fournier, for example, was mostly supportive.

Of course, those in that same class who feel a much more dramatic shakeup is in order weren’t so happy — on both the left and the right. On the Tea Party right, the nearly pavlovian accusations of RINO-ism abounded; and while the activist left is currently more focused on Sen. Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign than anything going on in Congress, some of its more influential voices were unhappy, too, with the deal’s cuts to Social Security earning the most criticism.

Given the most likely alternatives — a government shutdown and/or another debt-ceiling crisis — the deal is probably a good thing. But what was most significant about the agreement wasn’t, as Speaker Boehner implied, its simply happening. Such deals may be rare nowadays, but likely future-Speaker Paul Ryan struck one as recently as 2013. And it wasn’t that the so-called third rail of politics, Social Security, was included; the “rail” has been touched before, like in the 1980s.

No, this was the rare instance where process really is more important than policy. The most significant thing about the budget deal wasn’t anything actually within it, but rather how difficult it was to reach — and how extraordinary the circumstances were that allowed it to happen in the first place. The budget deal matters, in other words, because it stand as just the latest and most conspicuous proof that the American system of government is quite simply falling apart.

Think for a second about some of the cold, hard facts about the process that even its biggest supporters make no effort to deny. For one thing, a real motivation for striking the accord, on both sides, was to ensure that the issues of honoring the nation’s debt and funding its government were removed from the 2016 presidential campaign. That may seem obvious and even sensible at this point; and, fundamentally, it is. But let’s be sure to stop for a moment and appreciate what that means.

What it means is that the political system — which, remember, is supposed to be the ultimate arbiter of authority and legitimacy in a democratic republic — can no longer be relied on to achieve self-government’s most basic tasks. Even more remarkably, this isn’t the assessment of some angry outsider; it’s the conclusion of the participants themselves. It represents nothing less than Congress’ admitting it cannot be trusted and asking to have its power severely limited, if not quite stripped.

If we keep in mind that the Federalists’ bloodless handing-over of power to the Democratic-Republicans in 1800 is seen as a high-water mark in the American experiment, then surely this must be regarded as a low. The reason we have elections, after all, is so that such decisions about government funding and debt and so forth can be resolved after a period of debate and deliberation. This deal, struck as it was with 2016 at the forefront of everyone’s mind, effectively inverses that dynamic.

Another sign of democratic breakdown can be found in the deal itself, which leaves almost all of the details of how the government will spend its funding unaddressed. The idea is that the relevant committees in the House and Senate will make those decisions. That sounds fine on the face of it — but it’s an implicit acknowledgment that, like the deal itself, nothing can be done in Congress unless it’s opaque to the public. This is where the talk of “behind closed doors” comes in.

Last but not least, the deal signals a kind of structural breakdown is that the potential of another debt-ceiling crisis was necessary to precipitate it. This is already fast-fading into the mists of recent memory, but it wasn’t so long ago that the idea of using the debt ceiling to compel good self-government was seen as beyond the pale. You shouldn’t need a gun to your head to pay your bills — that was the logic. But we are now in the post-2011 era, clearly, and government-by-suicide is the new normal.

I’ve made this argument before, but I believe this may ultimately be seen as one of President Obama’s most important (and most regrettable) legacies. As Slate’s Jim Newell noted, striking a deal to lift the debt ceiling now requires the presence of a speaker willing to “blow himself up.” Boehner has referred to this as “cleaning the barn” for his successor. It’s a good thing the current speaker was willing to do this, of course; but it bodes very ill for the future. Not every speaker will be so willing.

Shares