This didn't used to be sort of thing a person comes back from. Trust me, I should know. And in the case of Jimmy Carter, it's a miraculous breakthrough for medicine, and a gift to the world that an extraordinary person gets to have more time in it. It's a sign of hope. It's not enough.

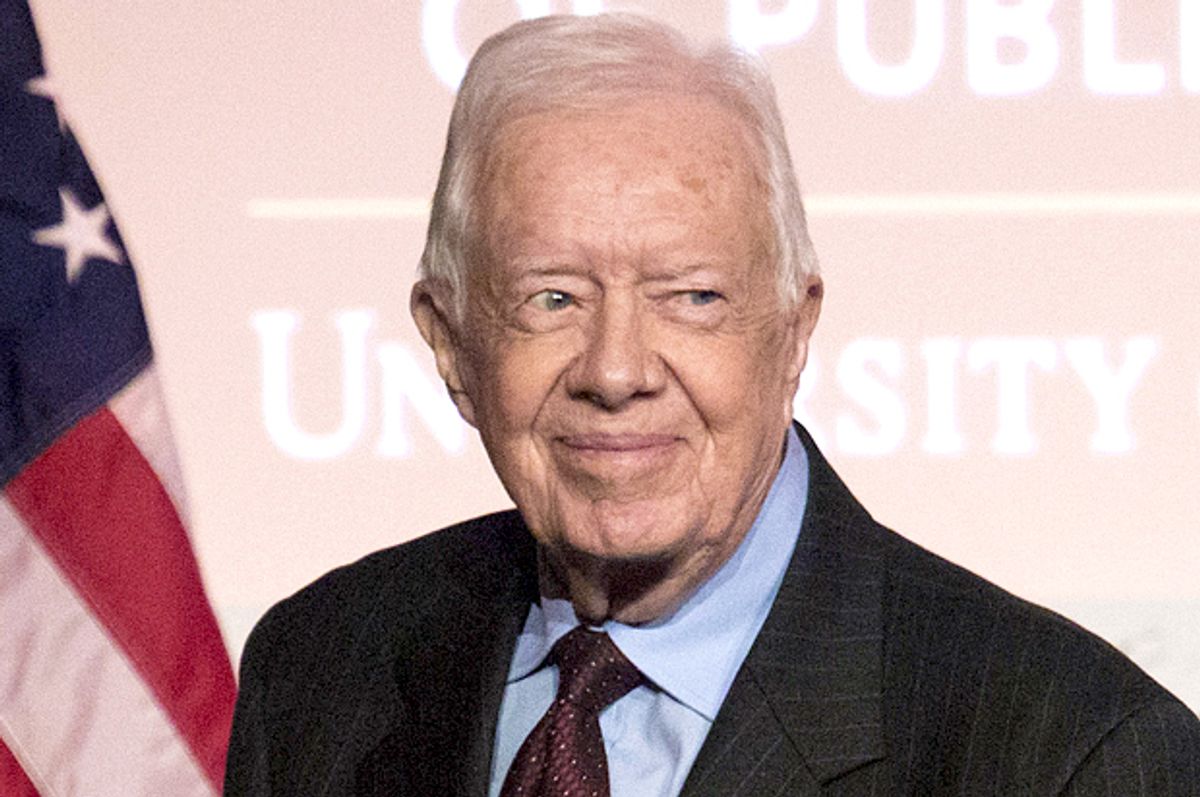

On Sunday, the 91 year-old former president of the United States made the extraordinary announcement — first to his fellow parishioners at the Sunday school at Plains' Maranatha Baptist Church — and then via an official statement from the Carter Center — that "My most recent MRI brain scan did not reveal any signs of the original cancer spots nor any new ones. I will continue to receive regular 3-week immunotherapy treatments of pembrolizumab."

In August, Carter announced that he had been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma — the deadliest form of skin cancer, and one that traditionally has offered few treatment options. As the LA Times reported at the time, "Former President Jimmy Carter can be thankful that he fell ill in 2015 instead of 2010." That just happens to be the year I was first diagnosed with melanoma —with a metastatic recurrence just a year later. It's a diagnosis that has typically offered patients a mere handful of months to live. As the Atlanta Journal Constitution noted this week, "Only a few years ago, Stage IV melanoma was tantamount to a death sentence."

But fortunately for people like Carter — and me — the field of treatment is changing rapidly. Thanks to an innovative clinical trial, I was one of the first individuals in the world to be treated with a combination of two drugs designed to essentially take the brakes off the immune system so it can be activated to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Three months after starting the trial, I presented no evidence of disease. I'll be four years cancer free next month. And I could not be more thrilled or hopeful that in October, my drug combination became the first combination immunotherapy treatment approved by the FDA. Last month, one of my drugs — Opdivo — was approved for use in renal cancer; just earlier this year it was also approved for non-small cell lung cancer. And that's just my two drugs. There are many more, including Carter's Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Meanwhile, ongoing immunotherapy clinical trials are also showing success with an array of other cancers.

But despite the cause for hope, there are limitations. This week, as I was describing my cancer treatment to a fellow writer, I mentioned that it has had a roughly 30% success rate. He — like my oncologist when she first got me into my clinical trial — seemed impressed with the number. But it's a lot less cause for celebration when you're the one with a fatal form of disease. It's certainly not the kind of chance you'd be thrilled to take in say, your birth control. USA Today notes that Carter's treatment offers similar odds, reporting this week that "About one-third of patients who take Keytruda get a benefit, either because the cancer shrinks or stops growing." What happens to the rest?

A few months ago, I became friends with a remarkable young woman, via a bond forged in one of the worst commonalities possible. Except for the gap in our ages, our stories were nearly identical. An initial diagnosis on melanoma on the scalp. Surgery — at the same facility and with the same surgeon. A seeming return to health, followed by a metastatic recurrence. Her doctor had been a fellow on my clinical trial; her first course of treatment employed similar science. The last time I saw her, at a friend's book party in late October, she was two days from starting on my drug combination. She said she was excited to get going. She looked healthy and full of hope — even when I noticed her with her eyes welling up as she watched the action up on stage. She had just passed the bar. She was 25. Less than three weeks later, she was gone. An announcement of her death noted her cancer, "which in her final weeks ceased responding to treatment." Because that's how it goes sometimes.

How does a 91 year-old former farmer get through metastatic melanoma on immunotherapy, and a sunscreen and hat-wearing twenty-something not? Why am I still here, when my doctor has told me that for my trial, the overall survival at two years was 50 percent? That's the next big mystery our doctors and researchers are trying to unlock — the enigma of why this type of therapy works so swiftly and so conclusively on some of us and not others, why it's a success with a leader with a lifetime of service behind him, but not a woman who should have had the same in front of her. I believe that scientists will find the answers. They just won't find them soon enough for all of us. So right now, our cancer treatment is still nothing short of miraculous. But I can't wait for the day it's entirely run of the mill.

Shares