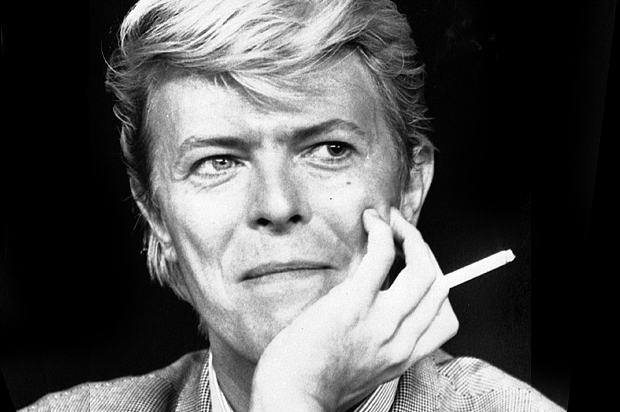

David Bowie shouldn’t have died. Certainly not before we did. He was the Thin White Duke, the Goblin King, and a vampire in a movie none of us have seen in 30 years, so we just assumed he was immortal. It is slim consolation that, upon his death, we get to write about how much he meant to us. He certainly meant everything to me.

David Robert Jones was born, as we all were, but from there our paths converged. While he made art out of life and life out of art, moving like a sylph through the caverns of our minds, we trudged through our ordinary existences, never suspecting that the little nuggets of weirdness inside us just needed a divine spark so we could become the celestial children we were always meant to be. But then Bowie appeared in our lives, and that spark exploded into infinity, letting us know that it would be OK if we just danced our own dance. Though never as well as him.

Some of us were fortunate enough to meet Bowie personally. In the bleak winter of 1989, as I banged away tunelessly on the keyboard in the basement of my college dorm, a stranger walked in, shivering, his face wrapped in bandages. Little did I know that this was a brief, almost unknown period where David Bowie was pretending to be a mummy in public. It was both his way of hiding but also of beautifully presaging his own death. Even 30 years ago, Bowie was teaching us how to die.

“Pardon me,” he said in a voice unfailingly polite and sophisticated, but also kind and ironic, “but my driver appears to have gotten lost. Do you have any way of knowing how to find the most expensive hotel in Chicago?”

What did I, a weak-muscled, confused, half-drunk college freshman, know about anything? I was so sad and alone and lost, my creativity bottled up, repressed, strangled like an unwanted wolf pup in the den. I told him I couldn’t help.

“Oh, that’s OK,” the mummy who was Bowie said. “But could you at least tell me where I could get a decent cup of tea?”

I began to sob.

“No,” I cried. “We only have Bigelow!”

He placed his elegant hand on my shoulder and said, kindly, “Hey, sad kid, it’s OK, don’t feel this way, you are a beautiful comet in the infinite universe.”

“Huh?” I said, as I looked up into the face of what appeared to be the Invisible Man in a slim-cut suit.

He sighed and began to unwrap his bandages. I sat there, mortified, expecting to behold some hideous creature fresh from facial-reconstruction surgery. But instead, with a kind smile, a glow emanating from his head as though he created his own light just by existing, stood David Bowie.

“I…I…saw you on TV,” I said. “When I was a kid.”

“Did my ever-changing persona give you the courage to feel weird, to embrace your burgeoning sexuality?” he asked.

“No,” I said, “I was more into Huey Lewis.”

Bowie took this in stride.

“You had bad taste,” he said. “Many people do. But I am here now to show you the way. Play your music.”

“You want to hear my music?”

“I want to hear the music of all the galaxy’s lost children,” he said. “By embracing the voices of those who are scared and alone, different, suburban, I give them power.”

“All right,” I said.

I banged the keys with about as much grace as a butcher tenderizing a strip steak.

“You didn’t invite me to your kegger,” I sang, tunelessly.

He slammed the keyboard cover down. I barely pulled my hands away in time. David Bowie stood there shaking his head.

“That’s enough,” he said. “I can tell when someone lacks a musical gift.”

My shoulders drooped despondently. I began to cry.

“I knew I was a loser,” I said.

“You pretty thing,” David Bowie said. “Don’t be sad. We all have our mark to make on the world.”

He studied my face as though I were a sculpture at the Uffizi, and then cradled my chin in the palm of his hand.

“I believe you have a great future writing snarky magazine articles,” he said. “It is your gift. Don’t ever lose that bitter cynicism, insecurity and self-hatred.”

Bowie had voiced my deepest desires, as he always did for everyone. I relaxed, at last. For the next half-hour, David Bowie and I drank shitty dorm tea and talked about life and having sex with androgynous supermodels. I asked him what Iggy Pop is really like and he said, “kind, like the dog he always wanted to be.” And then he wrapped himself up like a mummy again. “Find your inner nightmare,” he said, “for it will set you free.” With that, he disappeared into the frigid night.

Because I’m not much for talking about myself, I’ve never told anyone about my encounter with David Bowie. But now that he’s dead, people should know. David Bowie was my secret inspiration, my Star Man waiting in the sky. I was never more myself—like an extra-virgin version of myself, the kind in which you’d dip fresh-baked focaccia bread—than I was in the brief time I was with David Bowie. He built a bridge to my truest self, and I’ll always be grateful. Thank you, David Bowie. You’re the reason I became a writer.