Has anyone in rock music had more fun than Dave Stewart?

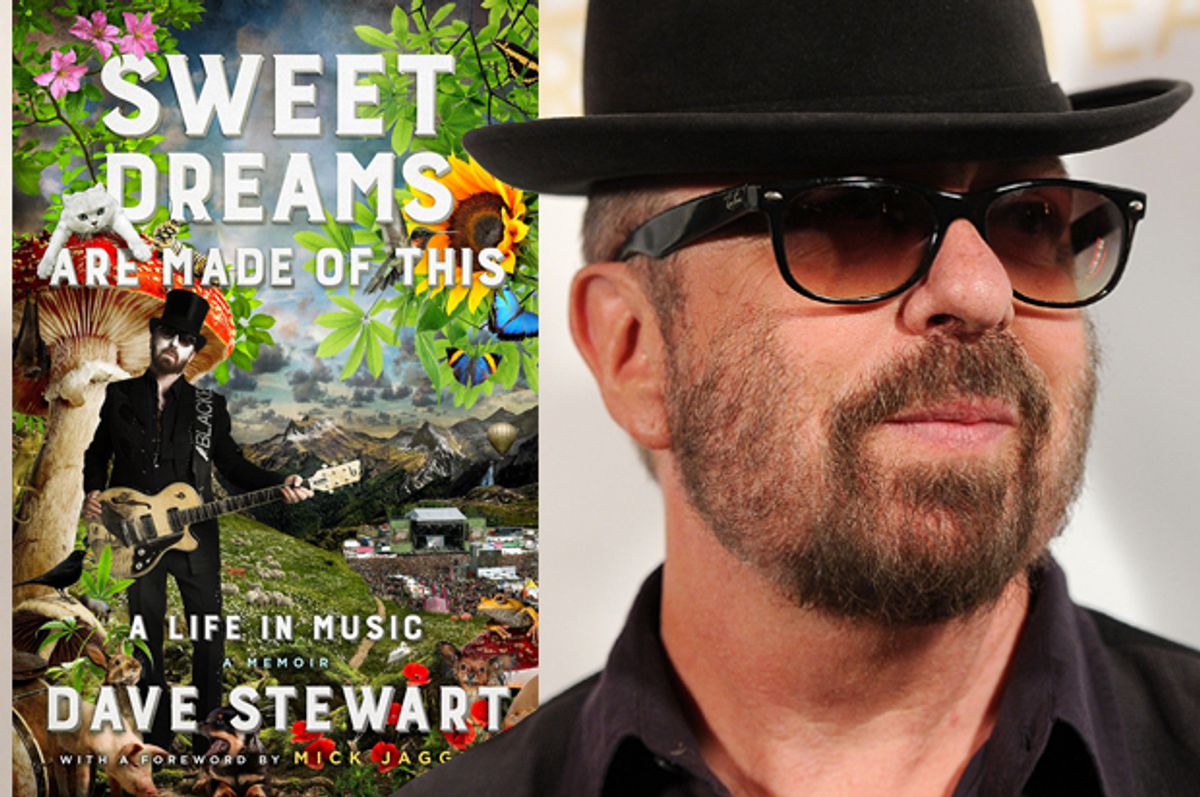

To a lot of people, he’ll always be the quiet half of Eurythmics. But Stewart has been a kind of Zelig of pop and rock music, working with Mick Jagger, Tom Petty, Damian Marley, Joss Stone and plenty of others. His new memoir, “Sweet Dreams Are Made of This,” chronicles his own career and includes appearances by Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin, as well as a great scene of his first meeting with future bandmate Annie Lennox. (The two, who were in a band called the Tourists before they formed Eurythmics, were romantically involved during some of their collaboration, but not all of it.)

Stewart, who grew up in the Northeast of England, started out as a young guitarist who loved British folk and American blues artists like Mississippi John Hurt. He even stowed away in the van of a progressive folk band called Amazing Blondel. He went from music that was committed to rock’s roots to becoming a pioneer of synth-pop, one of rock's most proudly artifice-driven styles.

Salon spoke to Stewart, who comes across as cheerily low-key, from his home in Los Angeles. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You seem to have worked in music for decades without getting jaded. What’s your secret?

I wasn’t jaded until I started writing the book and realizing all the different episodes and escapades — it aged me five years, I think. It’s going backwards. I think – and it’s the answer to your question – I never look backwards, so I’m always excited about a new artist, a new project… And how do we help music stay as a relevant commercial thing when everyone’s using it all over the place for free. And working on all sorts of projects. So I’m always looking forward at them. That keeps me excited about music and motivated. And working with a lot of new artists – I just produced five new artists in the last 18 months. Brand-new artists, as well as in between working with more normal or legend artists.

I think that balance is good. If you stay, all the time, in the world of the elite, and the rock ‘n’ roll royalty, you can forget about the excitement of music. But if you’re with new artists all the time, they are incredibly excited – that rubs off on you, and your experience rubs off on them. I think that’s what it is.

You’re most famous for being in Eurythmics, but you’ve been all over the place musically. Were there other periods of your career that were as exciting?

In the book, Eurythmics takes up a large chunk. Being with Annie, living together, being in a band together – that took nearly 20 years.

But obviously before that, I was this young kid that ran away in the back of a van. And when we arrived at our location, the roadies discovered me at 6 in the morning, all bleary-eyed. That was my first escapade of running away – begging them to let me stay and then ringing my dad. They let me stay and taught me a bit about what they were doing, with amplifiers and going to play gigs. That kind of escapade was thrilling – being 16 and away from home with a bunch of guys who were living off playing their music.

And living and sleeping on the floor with a painter, an artist, where the whole room was just empty and full of paint everywhere. Just that diving into, “Hey, there are people called artists, and all they do is this stuff, and they don’t care if they’re starving or if they make anything – they’re just doing it anyway.” That was a great lesson.

And Annie and I went through a period with eight pounds a week between us – that’s like $12 a week between us – living in a squat. That’s where someone takes over a house and don’t pay rent – it’s illegal.

Do you recommend being romantically involved with bandmates? Sounds tricky.

I think we were one of the few in the world who made it work. Mostly, it’s a recipe for disaster and breakup. But Annie and I were a couple before we were a band – we were just living together. We didn’t even write a song each or between us in the Tourists. Then when we formed Eurythmics and decided we would separate as a [couple] people were like, “What? You can’t do that. That’ll never work.” But actually we wrote about 140 songs. So in that way, it was highly recommended. Because the source of material never runs out. It’s such a well of material.

I decided to be a photographer for a few years, and met the whole art world that was beginning to break in England – Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas and Tracy Emin… They’d all be hanging around my apartment. It was a little bit like having a David Bowie lesson or an Andy Warhol lesson…. I had many adventures that would never have happened if I hadn’t jumped off head first.

Bowie makes a brief appearance in your book. What did his music mean to you?

His music was such a mind-blowing experience when I was a kid. One time when I was in London, I was playing “Hunky Dory,” and these Jehovah’s Witnesses rang the doorbell. Most of the time people don’t let them in. And I was so excited about this – “Life on Mars” and other tracks – that I brought them in. And I said, “Actually, I’m David Bowie.” They had no idea who we was. I played all these weird songs, and they said, “OK, we’ve had enough – nice to meet you.”

I met him many, many times… We went to see Big Audio Dynamite at the Ritz, sometime in the ‘80s. Talked about many things.

You’ve spent your life with musicians, some of whom had rough patches, and you had some very nasty bouts in the hospital. Are musicians more self-destructive than other people?

There has been a survey, in Australia, on artists in general, and their suicide rate is way higher than average – off the chart. Being an artist is tricky, because you don’t have schedule, you don’t have weekends off, you don’t have anything that relates to a regular existence, because it’s not a job. It’s a thing that’s going on in your head and it won’t stop.

So everybody who’s an artist is terribly insecure as well. It can manifest in an amazing David Bowie performer with lots of different characters. Or it can manifest in a Nick Drake way – it’s a tricky business.

Were the ‘80s the most decadent period for you?

Right when [Eurythmics] became huge, we’d broken up, and I was single for the first time in my life. Luckily, I’d stopped taking drugs. If I’d been single and taking drugs and hugely successful and wealthy, right at that point, it might have been a different story. But I’d been through all that when I was poor… Annie helped me get away from being addicted to speed.

I was transformed. I’d had this near-death experience where I was on a hospital table, for surgery, and I came out of it a completely different person. I wrote a graphic novel about the experience and called it “Walk In.” A walk in is where somebody’s heart stops beating of another soul or spirit sneaks into the body.

You got a new soul?

Yeah – I got a different, more alert… Before I was always stoned. I could play the guitar great… But suddenly I woke up and had almost a mission implanted in me. Annie couldn’t believe it. I bought some gear, and was making all these electronic sequences nonstop for 12 hours, without thinking about getting a cup of tea.

How old were you at this point?

I think I was 26 or 27. Everybody noticed the transformation: “Whoa, what’s happened to Dave?”

You mentioned the difficulty of music as a commercial possibility these days. How frustrating is that change to the digital world?

Now [digital companies] just want to put all our music up there, and we’ll sort it all out later. Of course, it’s not sorted out still. The food chain looks ridiculous when you look at the artist’s compensation on one end, and where the money is being sent, back and forth and around about and up and down.

I even made a funny tape where I rang YouTube and somebody asked, "Why are all these people uploading my music, all over the world, with billions of views, and I don’t see anything coming back to me on a statement? And every time I try to put up my own music, YouTube tells me to put it down." It’s a mess.

You seem to get along with everybody. Have you ever worked with a musician you couldn’t stand?

I’m never a gun for hire – usually I meet people, have dinner or drinks, become friends, then try a few tracks to see what they sound like.

But a couple times I’ve given in when a publisher has said, “You gotta meet this person and write a song.” Which I find really weird – how do you meet somebody and just sit down and write a song, when you don’t know anything about them. And those are usually a disaster. I usually come out of the room after half an hour yelling, “Help! Help!”

Shares