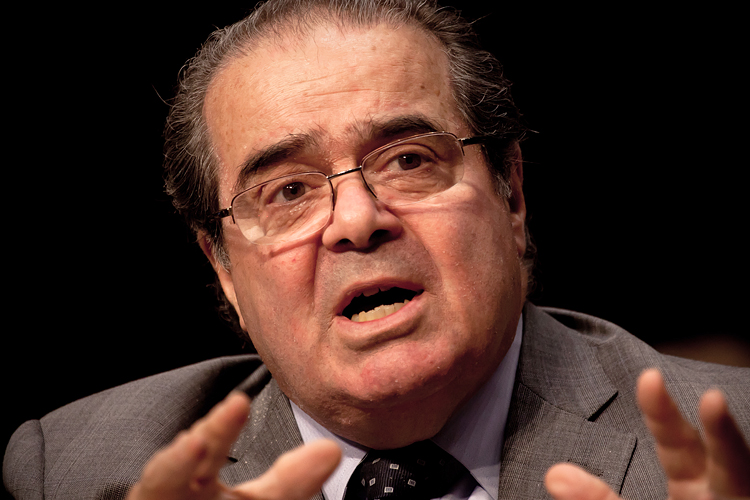

Eight years ago, I had the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to ask two questions of the country’s most famous conservative Supreme Court justice. I’ll never forget how he answered.

I was a junior in college at Washington University in St. Louis, an English major, but that spring I was spending a semester abroad at Christ Church, Oxford University. I was truly enjoying my tutorials in 19th century British novels, although to be honest, I was even more excited to be taking my meals in the actual Harry Potter dining hall.

My one complaint was that the American students were a little segregated from the rest of the student body, so I tried to expand my friend group by joining the Oxford Union Society. Founded in 1823, the Union is probably the world’s most famous debating club. It’s the historic training ground for prime ministers and politicians in the U.K. and throughout the former British Empire.

The Union regularly invites distinguished guests to debate or give speeches. When the notice came out that Justice Scalia would be visiting in February, I put my name in the drawing, thinking it would be a long shot. I was stunned by the email notifying me of my selection. Not only did I have a ticket to his speech on the Union floor, but I was one of 12 students selected for a private dinner and drinks with him beforehand!

My place setting was to the guest of honor’s left, to the relief of liberal family members when I told the story later. I was very nervous to be in the same room with such a famous jurist, but probably more anxious about the other students. At that point, I’d read very few judicial opinions. I fully expected to be embarrassed that these well-spoken Brits knew more than me about American constitutional law.

Mostly, I recall Justice Scalia making light conversation throughout the meal and seeming fully at ease. Of course, he had strong opinions on every subject that came up, whether it was the newly advanced EU constitution or Chelsea vs. Manchester United. He spoke fondly of Justice Ginsburg as his “best friend on the Court.” He said he hoped C-SPAN would one day record oral arguments because he’d obviously outperform his fellow justices. He agreed with one of the Rhodes scholars in attendance that his “Platonic golf” line was an all-time best.

After food came glasses of sherry. I gathered my courage and decided to ask the two questions I’d considered in advance.

“Justice Scalia, as we’re coming to the end of Bush’s presidency, I wondered if I could ask your opinion on the president’s leadership qualities.”

I recall Justice Scalia leaned back a little and examined my face. He may have thought I was a plant. Nonetheless, he was completely candid. “I have the utmost respect for the Bush family,” he said. “And I’m not a politician or a political figure. But a lot of my fellow Republicans think the other Bush brother is much brighter. That the wrong Bush brother became president.” There in the Gladstone Room of the historic Oxford Union, Justice Scalia indicated that he shared this opinion.

Flash forward to today: Jeb’s presidential campaign is on life support. It’s clear he does not have his brother’s political or interpersonal instincts. But I have a strong suspicion that Jeb would have had Justice Scalia’s support.

I had practiced my second question several times so that I could get it out easily. “Justice Scalia, if there’s one decision you would like reversed from your tenure on the Court, what would that be?”

He didn’t hesitate. “McConnell,” he said, referring to McConnell v. FEC. The case upheld the constitutionality of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002. The BCRA, more commonly called the McCain-Feingold Act, had put in place certain campaign finance rules for corporate and union spending in elections. The Court in 2003 upheld those reforms, and Justice Scalia issued a blistering dissent. As we drank sherry in Oxford, Justice Scalia employed one of his classic hyperboles. “If you’re not free to use money in the political process, then the First Amendment is dead.”

Justice Scalia would get his reversal just two years later. That case is huge and infamous – Citizens United v. FEC – which effectively wiped out bipartisan campaign finance reform and led directly to the super PACs and money free-for-all of the contemporary election cycle. Justice Scalia described his victories on the Court as “damned few,” but there’s no doubt Citizens United was a fundamental change.

We walked with Scalia toward the Union floor, where he was to give his pre-written speech. He told us he was rather disappointed that he wasn’t debating anybody that night. “I would have enjoyed it!” he said with a mischievous grin. But as it turned out, he got his wish anyway. When it came time for Q&A, he flipped every question back into an argument in support of his originalism. For example, when a student asked about slavery and the “three-fifths” clause of the Constitution, Justice Scalia said this was a perfect example of the system working well. That clause was nullified not by activist judges but by the passage of the 13th Amendment after the Civil War. The change had been made to the text itself.

Two and a half years after our meeting, I would enroll in law school at my St. Louis alma mater. I’m not a litigator, and don’t exactly subscribe to his strict constitutional interpretation. But I do wonder if Justice Scalia played a practical role in my law school decision.

“Wash. U., eh?” Justice Scalia had said, when I told him where I was in college back in the states. “You know, your old law school building used to be gray and boxy. Mudd Hall, think that was its name. Too modern. Very ugly. But I hear the new one is pretty nice.”

He was brilliant, he was polemical, he was a man of rigid principle, including in aesthetics. May he rest in peace.

Stephen Harrison is a writer and corporate lawyer for a tech company in Dallas.