Bernie Sanders is not going to be president. But in defeat he has accomplished something extraordinary, probably something more important than anything he could have achieved in four or eight frustrating years in the White House. For the first time since the end of the Cold War — and perhaps since the beginning of the Cold War — large numbers of Americans have begun to ask questions about capitalism. Questions about whether it works, and how, and for whose benefit. Questions about whether capitalism is really the indispensable companion of democracy, as we have confidently been told for the last century or so, and about how those two things interact in the real world.

Bernie Sanders did not invent those questions or cause them to emerge, to be sure. They have emerged from a whole range of objective conditions and subjective perceptions, including the dramatic worsening of economic inequality, the near-total paralysis of our political system and the awakening of an entire generation of young Americans, supposedly from the non-poor classes, who have graduated from college tens of thousands of dollars in debt. But Sanders has served as an important channel or catalyst for such questions and the shift in consciousness they represent. He or his advisers appeared to see or sense a rising current of discontent that took nearly everyone else by surprise.

After several generations in which a capitalist economy dominated by the neoliberal policy prescriptions of tax cuts, deregulation, privatization and fiscal austerity has been understood as the natural order of things — and as the oxygen necessary to nourish democracy around the world — the Western world’s entire leadership caste has been startled to encounter a resurgence of systematic nonbelief. To the bankers and politicians, it feels almost as if a crusty old Vermonter had come close to stealing a major-party presidential nomination on a platform of Flat-Earthism, or by professing that the moon landing was a fake. (Those politics, to be fair, are largely confined to the other party.)

For many decades, all lingering remnants of nonbelief in the goodness and naturalness and blessedness of capitalism have been endlessly derided and driven to the margins of political discourse, which now looks like an admission of weakness or the work of a bad conscience. In the United States, “socialism” became a bad word, apparently poisoned forever by the disastrous failures of Eastern-bloc Communism. (While the situation has always been different in Europe, most of the so-called socialist parties have drifted steadily rightward and embraced market ideology.) Pockets of socialist or Marxist thought could be found in the groves of academe, layered in dust, but in the realm of politics those terms belonged only to zealots and weirdos. Cornel West’s pre-Bernie quest for an alternative radical politics, for instance, led him into the arms of Bob Avakian and the Revolutionary Communist Party, a tiny Maoist sect that has haunted the far left since the mid-’70s.

In its eagerness to avoid all such associations, the Democratic Party has spent the last few decades prostrating itself before the temple of Big Money — a process greatly accelerated under the husband of its current frontrunner — and renouncing any semblance of class-based politics or egalitarian economics. You can almost understand why West found Avakian’s revolutionary fantasies refreshing, or at least honest. (The six-hour videos are tough to take.) What the Sanders insurgency has exposed, even more clearly than usual, is that the Democratic Party does not represent the material interests of most of the people who vote for it. (This is of course even more true of the Republican Party.) Those who insist, in tones resonant of “get off my lawn,” that it’s time for Sanders voters to grow up and support Hillary Clinton in the name of party unity are missing the point of the 2016 campaign, perhaps deliberately.

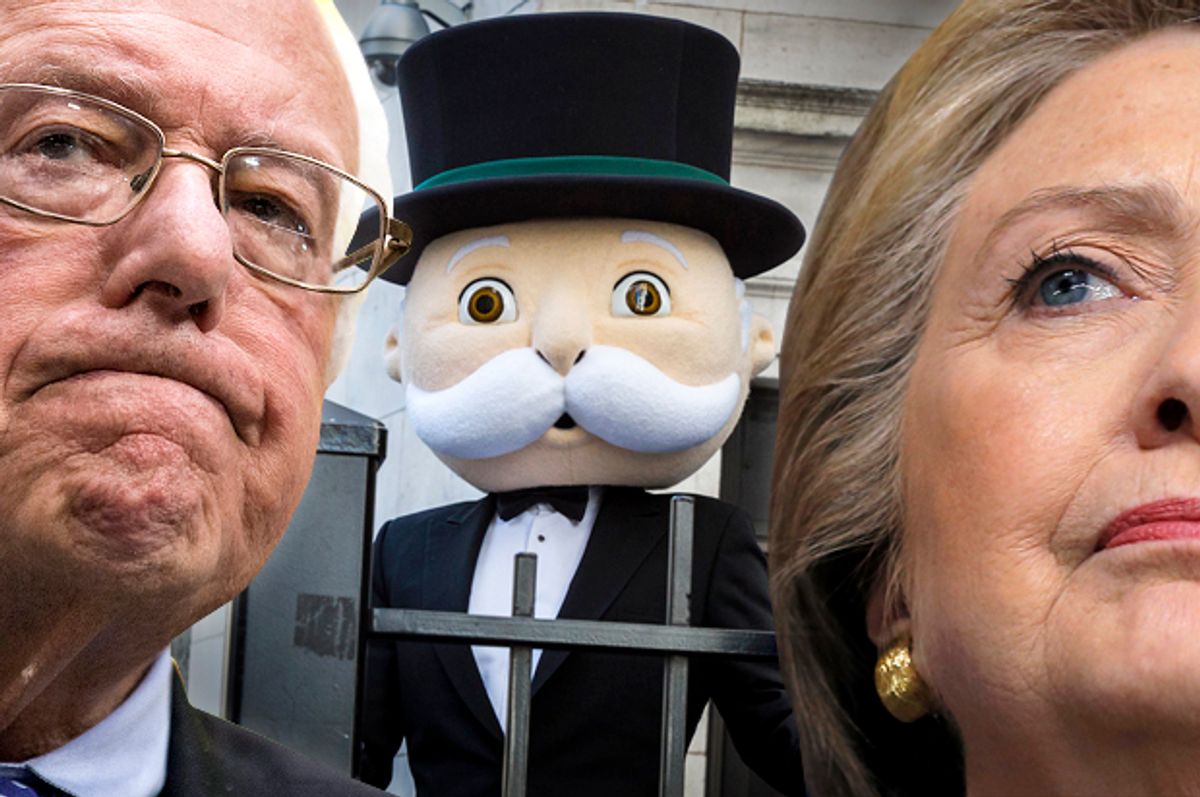

That Clinton is preferable to Donald Trump or Ted Cruz in the near term, for most Sanders supporters, is not in question. But the assertion that we need to get over all this nonsense about “free stuff” and get back to real politics is itself a tactic of warfare, in an overarching conflict that will long outlive this particular nomination battle. The division between Clinton and Sanders is more than symbolic or semiotic, as the 2008 division between Clinton and Barack Obama largely was. Hillary Clinton stands with and for capitalism, forcefully and forthrightly. Sanders’ position is more paradoxical, perhaps of necessity, but let’s put it this way: He stands outside capitalism and to some degree against capitalism, far more so than any American presidential candidate of living memory.

The Sanders campaign was an attempt to seize power in the Democratic Party, largely from outside, and renounce its allegiance to capitalism and its subservience to the entire package of economic, ideological and military imperialism sometimes called the “Washington consensus.” The true danger that campaign presented to the American political establishment lay not so much in Bernie Sanders himself — an unlikely candidate, and a less likely nominee — as in the heretical ideas it embodied, which may now prove difficult to contain.

I never thought that Sanders had any realistic shot at beating Clinton. (He got closer than I ever expected.) Furthermore, I was never convinced that was a viable solution to any of our problems. Sanders calls himself a socialist, at least sometimes, and within his coy or imprecise rhetoric about “political revolution” you can discern an awareness that revolutions don’t start from the top, and that their goals cannot be achieved by electing a new figurehead. I voted for Sanders in the New York primary, for all the good that did anyone, but Hillary Clinton’s supporters have had a viable case all along that given the system we have, she makes a more plausible chief executive for the corroded American republic.

The problem, of course, is precisely that: The system we have doesn’t work. Maybe it used to work a whole lot better than it does now, and maybe it just looked that way — that’s a tendentious historical debate that speaks to important underlying questions, but we’d better set it aside for now. But almost no one, across the ideological spectrum, will try to convince you that the interlocking systems of American politics and the American economy are functioning smoothly for the benefit of all. Reckoning with that political and material reality has required impressive rhetorical agility from Clinton, who more than any other current or former 2016 candidate stands at the intersection of those systems and represents their promise of stability and order. But then, no one has ever accused her of an unwillingness to change her mind, or an inability to mold her language to the moment.

Last week I took a first stab at drawing lessons from V.I. Lenin and the October Revolution and applying them to this dramatic but quite different historical moment. That was widely misinterpreted, not least because (as some readers were eager to point out) my analysis was pretty half-baked. I did not seek to imply any political resemblance between Lenin and Bernie Sanders, beyond a kind of analogy: Sanders perceived the decrepit Democratic Party roughly the way Lenin saw the crumbling Russian state, as an apparently powerful institution that in reality was ripe for revolutionary takeover.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks remain intriguing today, not to mention frightening, because of their abundant contradictions: How did a brilliant analysis of global capitalism in crisis, which seems almost eerily trenchant a century later, lead to such a dismal outcome? If capitalism is no longer to be viewed as the unalterable end-stage of history, and socialism is no longer an untouchable concept, maybe we can also get past the superstitious notion that every idea and insight that fed into the Russian Revolution inevitably produced the nightmarish Soviet state that followed. I feel quite sure that Bernie Sanders does not envision the overthrow of all political institutions or the seizure of all private property. His real relationship to the Bolshevik founder is a rhetorical and analytical one, and I find it implausible that Sanders is unaware of this.

One of the big crowd-pleasing crescendos in Sanders’ standard stump speech comes after he lays out a few startling symptoms of economic inequality: the top one-tenth of 1 percent of the population owns more wealth than the bottom 90 percent, and one wealthy family (the Waltons, of Wal-Mart fame) is richer than the poorest two quintiles of the population, or roughly 120 million people put together. He mentions the Koch brothers and the Citizens United ruling and the apparent fact that roughly 400 families have contributed the bulk of SuperPAC funding in this electoral cycle. “That doesn’t sound like democracy to me,” Sanders roars. “That sounds like oligarchy!”

As he is surely aware, that echoes a central tenet of Marxist political economy, one formulated by Lenin with particular vigor: When “bourgeois democracy” of the American or European sort is dominated by finance capital, such democracy becomes a mere form, a shell of itself. “Finance capital strives for domination, not freedom,” wrote the Marxist economist Rudolf Hilferding. In an essay published just before the October Revolution, Lenin uses virtually the same formula as Sanders, describing a pattern of “economic annexation” by which “imperialism seeks to replace democracy generally by oligarchy.”

In his best-known essay, “The State and Revolution” — the one used as a manifesto, for better or worse, by generations of future revolutionaries around the world — Lenin takes this analysis further still, in a way that suggests the obvious limits or potential paradoxes of the “political revolution” invoked by Sanders. Wealth becomes all-powerful in a “democratic republic,” Lenin writes, because it does not need to rely on “defects in the political machinery or on the faulty political shell of capitalism. A democratic republic is the best possible political shell for capitalism and, therefore, once capitalism has gained possession of this very best shell … it establishes its power so securely, so firmly, that no change of persons, institutions or parties in the bourgeois-democratic republic can shake it.”

If that seems to describe the political and economic crisis of the United States in 2016 with almost uncanny precision — far more accurately than it described Russia in 1917, I would say — it does not follow that Lenin’s prescription for violent revolution offers a viable solution to the quandary. For one thing, no such mass action is remotely conceivable in a social economy of disaffected individual consumers, segmented into a million micro-niches, rather than a factory-bred proletariat that already understood itself in collective terms.

Bernie Sanders served as accidental midwife at the birth of something thoroughly unexpected, the first faint glimmers of what the Marxists would have called a revolutionary consciousness. Where that will lead is anyone’s guess, but don’t be too sure that it leads nowhere and that the normative political order will soon be restored. Defenders of the system have mounted a forceful counterattack, but their confidence is too high and their vision of the future too limited. The threat of “political revolution” can no doubt be dispelled, for now. But the conditions that produced it — the intertwined failures of capitalism and democracy, as described by two socialist leaders a century apart — present problems that President Hillary Clinton cannot hope to solve.

Shares