For the past few years, I’ve had a tumultuous relationship with Facebook. A few days ago, I was reminded why.

I was at an afterthought of a campus fitness center, sandwiched between a ’90s step climber and the loudest treadmill known to man on a lonely spinning bike, pedaling my way through a 45-minute routine I’d internalized from the cycling studio I frequented before my husband I moved across the country. Want to see something comical? Find me on the bike, riding to the beat of my own drum. I have zero rhythm, so my self-directed spinning is a lot of erratic standing up and sitting down (“jumps”), clunking my sternum on the handlebars (“wide arm presses”), and running my legs like a rabid hamster on a wheel (“sprinting”).

Still, despite the general flailing quality of my workout, I sweated, got breathless, and achieved a mental state of honed motivation. Maybe it was the inspirational poster taped to the otherwise-blank wall my bike faced: a man’s long, brown forearm palms a ruddy basketball. Superimposed over the image are the words “Winners never quit and quitters never win.”

We have Vince Lombardi to thank for this kick-in-the-pants of a sentence—and as I slowed my pedaling (“this is how we go home,” I could hear my old spinning instructor yelling), I felt like I’d already won. So it wasn’t quitting when I looked at my phone, and it wasn’t quitting when I checked Facebook—that’s what I told myself. What was quitting was me abandoning the bike as I started to read the post of an acquaintance, a woman who had that day lost her dad.

“I didn’t expect to have such a short time with him,” the woman admitted. News like this always wrecks me—a week earlier, a man with whom I’d only occasionally played poker in grad school shared paragraphs about his just-deceased dad, paragraphs at which I wept until I finally quarantined myself in the bathroom—but this woman’s loss hit me more personally: her father and mine share the same first name.

I’d rather not mention that name. After all, one of the reasons I’ve long been freaked out about Facebook is because I was raised—by my parents, but especially by my dad—to be a private person.

How does that work for a writer? You might ask yourself. Not super well, is how I respond. And yet, surely Vince Lombardi has applicable wisdom: “The measure of who we are is what we do with what we have.” I’ve been fortunate enough to develop the confidence to believe that what I have is my mind and my voice, and for that I need to thank my dad.

He’s alive and well, I should add, but hey—there’s a fair chance he might not read this. I’m pretty sure a part of him still wishes I’d done something involving math. I have a solid suspicion that he only finds my writing when my mom shows it to him—and that’s okay.

***

When I was a kid, I saw other dads. They were everywhere, wearing Hawaiian shirts and mustaches, carrying wallets and drinking beers. They were at family gatherings, doling out noogies, stewing in corners. On television, they gave stumbling advice or blathered into obnoxious temper tantrums or flaunted their cosmic ineptitude at the flames of the charcoal grill. Sitcom dads got teased by wives and taunted by children until the moment of crisis, when violins swelled, and fatherly advice was proffered like Bactine for a skinned knee. It hurts but it’s good.

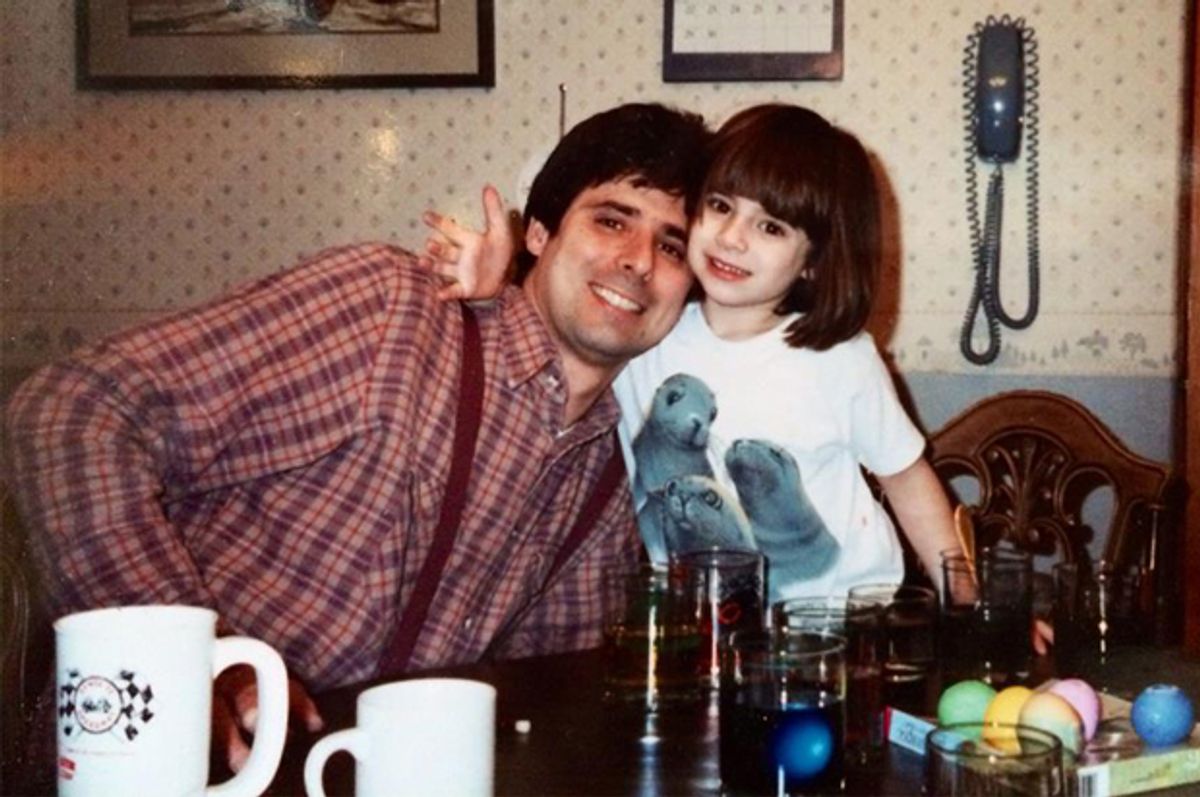

The dads I met in real life wore shirts and mustaches, too, but they also wore red vests and headdresses. My dad was one of them. For tens years, he and I participated in a program called Indian Princesses. Let’s not linger on the political incorrectness. Sponsored by the local YMCA, this father-daughter bonding jamboree was like Girl Scouts without the prissiness or the cookies. We held monthly meetings (crafts for the daughters, cigars for the dads) and went on campouts where we practiced archery, paddled aluminum canoes, rode slow horses, and climbed rock towers with names like Mount Wood.

We had nicknames, too, like “Singing Bird” and “Screaming Eagle.” That was me and my dad, the quietest members of the “Arapaho tribe.”

To tell you the truth, I envied the other girls with their jouncy dads. Now, I’m in my thirties, and my peers are dads like those guys—they all majored in communications or marketing. The other Arapaho dads were outgoing and funny, especially “Hairy Chest,” who could send the entire tribe into a giggle fit with Elvis impersonations. I envied girls with braggy dads who boasted of their daughter’s accuracy at the rifle range; girls with lenient dads, who let their the daughters fork tunnels through mess hall mashed potatoes. I even envied the other dads, who encouraged me to goof around and my dad to crack a grin over late-night games of Hearts.

I’m not sure when the envying wore off, but one year it did, like a puddle on hot asphalt, gone in an instant. Perhaps I’d turned ten, a double-digit age that meant adult. Instead of wanting a dad who treated me like a princess—and not just like an Indian Princess, but a princess princess—I became grateful for the way my father held me to a higher standard.

That’s what it felt like, anyhow, when it was just the two of us in a canoe, paddling down the Rock River under the steady gaze of the towering statue, Black Hawk (or The Eternal Indian). Rowing is hard, and it’s especially hard when you’re a twelve-year-old girl who can’t even do a push-up. Other canoes ferried groups of four: two dads and two daughters so the Princesses wouldn’t have to do the grunt work. In our vessel, it was just Screaming Eagle and me.

My friends waved as they passed us by. I could hear them singing along with the Spice Girls and Green Day and No Doubt they played on their portable CD players. My hands were already blistering, I could tell; they smarted when I repositioned them on the oars. But even though we were perpetually getting lodged in rocks, the prow of our canoe smacking into sand and silt, even though our journey down the river took twice the time of the other Arapahos and sometimes we heard nothing but the sound of our paddles slapping the water, an invisible fish leaping, my dad and I were steering that boat together, Singing Bird and Screaming Eagle, fueled by the cans of Canfields Diet Crème Soda he’d stashed in the pockets of his windbreaker.

***

Winners never quit and quitters never win: My dad taught me there are so many ways to win every day. Winning is a personal matrix, the little choices that add up to character. Of course winning is reaching the top of Mount Wood before anyone else (the way my best friend did, dinging a hidden bell), but winning is also dealing with wet dock shoes when your daughter can’t get the hang of placing just the blade—and not the oar’s shaft—in the water. Winning is being together in the canoe.

Winning, my father taught me, is using one plate instead of two, is drinking the morning’s cold coffee instead of buying a Starbucks in the middle of the afternoon. Winning isn’t not procrastinating—winning is staying up all night when you have a project or a report due the next day, when you have a deadline, when you have the stamina to think a little harder. Winning, my dad taught me, is thinking, thinking not only in an intellectual context, but thinking about the person you want to be in this world.

Are you a person who’s ever had to buy a snack from the gas station? A person who’s been on a road trip and wondered about the cheapest snack? FYI, it’s the Planter’s peanut tube, $.59 for one or 2/$1, which is why you’ll always find a sleeve of Heat Peanuts in my glove compartment. Does my dad love peanuts? Not particularly. He loves the value of a dollar. Because a dollar isn’t just a dollar, but a thought, a question, a quandary, a choice: How do you want to use what you’ve earned?

There are all kinds of facts I could tell you about my father, but none of those would begin to explain why I feel closest to him in my family. He may know the least about me: I would be ashamed, for instance, if he knew how much money I’d spent on clothes, shoes, purses, even books—after all, I learned as a teenager, CDs were a waste. “What are you going to do with those?” my dad would ask me when I filled an under-the-bed plastic storage container with music. I was incredulous then—and incredulous again, last year, when I returned to my parent’s house and dumped all those CDs at Goodwill.

He doesn’t know my darkest secrets and, on the surface, we have so little in common. He likes ribs; I like tuna tartare. He likes “cocoa mocho frappuccinos”; I like espresso and water. He likes his half-acre of lawn; I like city blocks. His vices are seeing a rebirth (stop smoking, Dad); mine (ice cream has yet to find its way into my new refrigerator) are in constant curtailment. And yet when we talk on the phone, we can spend an hour comparing our dogs and our weather, our jobs and our politics, and I marvel that two people can feel so close. I wonder if he feels that way, too.

What, then, is that space between the river’s bottom and the froth the canoe leaves in its wake on the surface? If neither our secrets nor our affinities bind me and my father, what does? Somehow, that mysterious something seems bigger, and though I’m not a math person like my dad, I’m certain the middle darkness of a river encompasses its greatest area.

Is this nuance? Logic? Pondering? Or simple curiosity? Whatever that quality of thought is that leads me to ask questions about the top and the bottom, the end and the beginning—that quality of thought is a product of my dad, and it’s nothing I’d ever be able to fit into a Facebook post. After all, he would hate to think that strangers were learning so much about him.

This isn’t to begrudge those who share their losses on social media—it’s only to say I know, in the pit of my stomach, that when that time comes, for me to do so would be to wrong my dad.

For now, I say sorry. Because Father’s Day is coming and I can’t not think about how lucky I am to have the Dad I do. I want to honor our relationship—as quiet and indefinable as it might be—while he’s around to hear it. Yes, I’m thankful for his wisdom and quirks, grateful for everything he’s taught me about the world. But I’m also glad for everything he hasn’t taught me. He hasn’t taught me to be dependent on men; he hasn’t taught me to see myself as an enemy or a princess—in fact, by seeing me as a person with a mind and a heart rather than as a woman, he’s taught me to look past some of the most biological parts of myself.

Most days, I’m ambivalent-to-disinterested in starting a family. Show me a baby and, reflexively as a knee tapped with one of those tiny hammers, I’ll cringe. There’s only one thing that starts to sway me, and given the context of this confession, it should come as no surprise: it’s my father. I can see exactly one good thing about having children, and that the chance to introduce a young person to my dad.

He’s the sort of understated person who can’t be summed up in a Lombardi-ism. He’s not a coach or a champ, a jock or geek. He’s the quiet, goofy, introspective, dog-loving man who taught me to guard myself and my privacy, to honor my thoughts—and the man who grants me the courage to give all that away.

Shares