Nostalgia is a longing in the present for a past that did not actually exist. The feelings and emotions elicited by nostalgia are warm and fuzzy. Nostalgia can be commodified, reduced to just a product, and (re)circulated for profit by the culture industry. Sometimes nostalgia can generate a feeling of anger at what is perceived to be lost, those “good old days” or “simpler times” thought to be long gone. But such longings for the “good” in the “good old days” and the “simple” in “simpler times” almost always fall apart under any level of critical scrutiny.

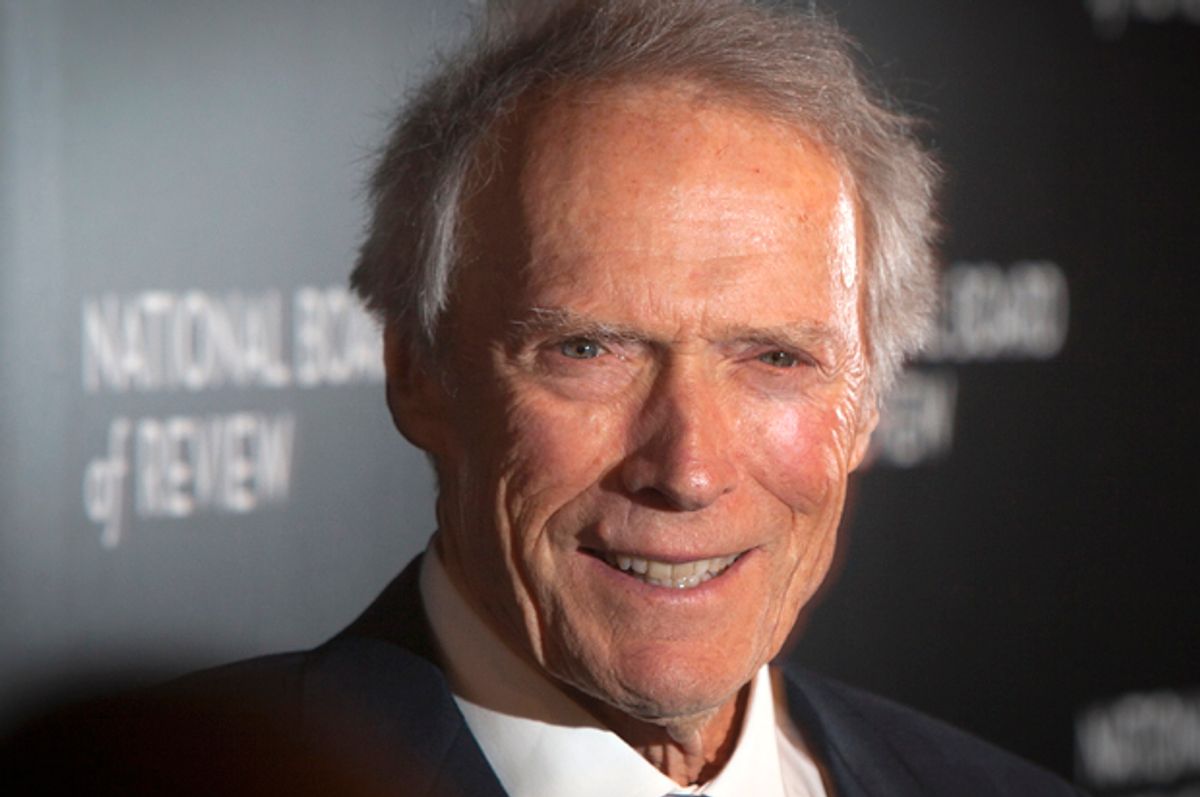

Last week, Hollywood legend Clint Eastwood fell into the nostalgia trap with his comments in an interview with Esquire magazine. There, Eastwood said about Donald Trump that:

He's onto something, because secretly everybody's getting tired of political correctness, kissing up. That's the kiss-ass generation we're in right now. We're really in a pussy generation. Everybody's walking on eggshells. We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren't called racist…The press and everybody's going, 'Oh, well, that's racist,' and they're making a big hoodoo out of it. Just fucking get over it. It's a sad time in history.

Eastwood faced criticism for those comments because they were perceived by some to be poorly timed in a moment when the United States is grappling with extreme political polarization and right-wing faux populism in the form of Donald Trump and his takeover of the Republican Party. Others were upset because when the divide between the Hollywood persona and the true self is dropped, fans and the public often discover something unappealing. Celebrities are not “real” people; they are commodified projections that are idolized by fans. To disrupt this relationship is to invite upsetness.

Eastwood has not been known to stand mute about his political opinions; that he chose to share his thoughts about “political correctness” and Donald Trump should not be a shock.

But most importantly, in a moment when white identity politics and right-wing revanchism and reactionary conservatism are dueling with a hopeful and progressive vision of America’s past, present, and future, is that Clint Eastwood (like many Americans of a particular age and gender and racial background) is fundamentally incorrect in his reading of the country’s past and how it subsequently resonates in the present.

Clint Eastwood is 86-years-old. In his lifetime he has seen a world war, the Holocaust, the collapse of the British and French colonial empires, the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union, the rise of neoliberalism, the information age and Internet, the specter of “Islamic terrorism,” and China as (near) global peer competitor for the United States. In the same time frame, Clint Eastwood saw the fall of Jim and Jane Crow and the triumphs of the civil rights movement, the successes it spawned in the form of the women’s and gay right’s movements, the election of the United States’ first black president (twice) and a country that is on the verge of electing its first female president, Hillary Clinton.

To have witnessed and been a party to such changes is likely both exhilarating and unsettling. But the present that Eastwood bemoans, and the “political correctness” he derides, were not born whole and complete like Athena out of Zeus’ head. Their origins are found across many moments in modern American history.

Left-wing and other activists were actively working for racial and gender equality throughout the 20th century. Elite opinion leaders in philanthropic organizations (and what would later be known as “think tanks”) were funding initiatives in response to the horrors of the Holocaust to educate the American people about how 1) race is a social construct and a fiction, and 2) a notion that race is a biological fact was antithetical to the American creed. Entire academic disciplines and subfields were funded and later expanded after World War 2—and especially in response to the tumult of the 1960s—with the goal of producing new knowledge and epistemological frameworks for understanding the changes that American (and global) society were experiencing around questions of ethnic and racial identity, group belonging, the nation state, and power.

Civil society organizations such as the NAACP and others actively worked to influence America’s public discourse on race and the specific language and norms that should guide it. While not always progressive or radical enough, the United States military and other parts of the American state also worked to challenge standing norms about the color line, as well as gender. Contrary to Eastwood’s assertion that, “When I grew up, those things weren't called racist” there were in fact many Americans who struggled, both publicly and on a mass stage, as well as in their own small corners of the world, for respect and human dignity. Ultimately, the white male heterosexual gaze is neither universal nor omnipotent. Moreover, the white male heterosexual gaze is not a type of racial panopticon. It is myopic and often blind to the realities of the world and the lived experiences of the Other. It misses more than it actually sees.

Eastwood’s seduction by a particular type of conservative nostalgia should not be a surprise because many of his most iconic roles have themselves been based on a mythic and imagined American past. Many of Eastwood’s early successes (and later with the Oscar-winner “Unforgiven”) were movies in the cowboy film-western genre. While Eastwood is most famous for his “spaghetti westerns,” the broader genre is based on a distorted view of American Exceptionalism, Manifest Destiny, and the country’s national character.

For example, the Hollywood western often depicts a world of merciless violence, radical autonomy balanced with communal values, and unrestrained gun culture. In reality, most communities in the old American West were less violent than major cities and had strict gun control laws. Mining camps and other communities were very often self-regulated and had people's committees or other groups that kept the peace and established rules for order. The American western film genre features repeated themes of yeoman farmers with Jeffersonian ethics trying to make a living in the face of robber barons, industrial power, railroads, or some other interloper who would jeopardize their freedom and prosperity. Again, those relationships were much more complicated and not as idyllic or exploitative as neat filmic binaries often suggest. And in the classic American western, people of color are usually victims of racial erasure or depicted as stereotypes. Women are peripheral (unless they are used as objects of masculine desire or in need of protection) to the white masculine narrative frame.

[And of course, while American westerns often feature ex-Confederate soldiers, curiously, few of them ever owned black human property. If these white men did own slaves, they were “kind” and "benevolent” towards them. Or alternatively, these ex-Confederates were opposed to the enslavement of black people. The former were good men who either fought for a “noble” lost cause or were closeted abolitionists who went west to avoid the country’s second original sin. This pattern continues in the present with AMC’s TV series “Hell on Wheels.”]

In a moment when American politics is dominated by discussions of Donald Trump, a man who is a Nixon and George Wallace-like hybrid, one entry in Clint Eastwood’s film oeuvre resonates in a particularly disturbing way. The critically acclaimed film "The Outlaw Josey Wales" is one of Eastwood’s 1970s era American western films. It was based on a book written in 1972 by Forrest Carter, a.k.a Asa Carter, a white supremacist, Ku Klux Klan member, and speech writer for rabid segregationist George Wallace. While Eastwood denies that he had any knowledge of the source material’s origins, its racist themes resonate throughout the film.

As Jim Cullen suggests in his book “Sensing the Past,” if popular culture does indeed provide an insight into the more formal political sphere, Clint Eastwood’s nostalgia, support for Donald Trump, and complaints about political correctness are reflected by a range of films that are both ideologically conservative while in other ways being very forward thinking and progressive.

Eastwood’s “High Plains Drifter” features his anti-hero character raping a woman until she “likes” it and is “enraptured” by pleasure. But Eastwood’s 2002 film “Blood Work,” which is a deconstruction of his 1980s Ronald Reagan hero and toxic white masculinity fueled “Dirty Harry” character, has him alive because of a heart transplant provided by a Latina, falling in love with her sister, and becoming part of her family. Clint Eastwood would also pursue passion projects about the African-American jazz legend Charlie Parker, feature the Monterey Jazz Festival in his misogynistic paranoid thriller “Play Misty for Me,” offer a revisionist western in the modern classic “Unforgiven” with co-star Morgan Freeman, and then navigate the complicated relationship of race and class beyond the black/white binary in “Gran Torino.”

The deflection that Clint Eastwood and other white men of a certain generation who are rebelling against “political correctness” are simply “products of their time” and should just be ignored as living anachronisms is lazy thinking. It is also dangerous: the Right-wing authoritarian and proto-fascist inclinations of Donald Trump and the Republican Party are fueled by lies about whiteness, masculinity, and power that sit dead center at the heart of conservative and revanchist nostalgia.

There were white men of Eastwood’s generation who wanted a more humane and just American society (as well as world) and struggled to create it. The United States is much more cosmopolitan, inclusive, and diverse than it was during their youth and earlier adulthood because of their efforts. Clint Eastwood should be criticized not because he transgressed some imagined (and I would suggest all too much creeping and expansive) line of “political correctness,” but because like many conservatives and libertarians he confuses nostalgia with historic fact and truth.

Shares