I was rummaging through the laundry I’d just poured on my bed, looking for my daughter’s soccer jersey, when the stack of white pages caught my eye. It was the full draft of the memoir that I’d given my husband Mark to read almost six months ago, and it sat on his dresser covered in a fine layer of dust. Harried, annoyed at the constant need to rush as well as the mess, I said aloud what I usually just thought to myself.

“I can’t believe you still haven’t read my manuscript.”

“I haven’t had time!” He was bending over the other side of the bed, searching the pile for the shirt he was supposed to wear as the team’s assistant coach. “Every minute I get to read, it’s for my class.”

He was enrolled in graduate school, taught art at a middle school, and did freelance work on the side. But despite how hectic his days were, I was keenly aware that he’d had some chances.

“There was winter break,” I pushed back. “And spring break.” I didn’t add that he’d watched plenty of TV.

As was frequently the case, the moment wasn’t right for us to talk through the conflict. Our youngest child was calling us from downstairs to say she couldn’t find her cleats. The laundry wasn’t done, nor was the grocery shopping. The next day would start another busy week, where our typical schedule had my husband leaving for work before 6:00 a.m. and me returning from my own job 12 hours later.

The opportunity for us to be alone together was limited to begin with, and in my scant free time I often stole away to write. I’d been working for three years on the story of how I interpreted my early childhood sexual abuse at different points in my development, a project that required me to revisit uncomfortable memories and to research sexual assault and pedophilia.

The dissonance between this difficult material and our cozy family life could make me agitated, but I didn’t talk about it much during the late-evening hours on weekends when my husband and I could connect. Our instinct was to relax in each other’s company then, hanging out with friends or curling up on the couch for a show. My manuscript represented to me the complicated internal life I still hoped to share with him but didn’t have the energy to talk about, and his reluctance to read it felt like a lack of interest in the parts of me that didn’t operate as a co-parent. It sometimes also felt like disapproval.

We hadn’t always needed to put things in writing to communicate on deeper levels, of course. Some of the chapters in the memoir cover our early years together, which were heavy on chatty dinners and walks along Lake Michigan. He’d already heard plenty of the anecdotes I was writing about, but my interpretations of them had shifted, and I wanted him to follow where my thinking had gone. I also wanted his take on how I wrote about us.

An important scene in the memoir occurs on our fourth date. Having made out thrillingly the last time we’d seen each other, we were giddy with the certainty that on this evening we were heading to bed for the first time. We couldn’t stop kissing each other at a neighborhood bar where we sat on a tucked-away couch. I pulled away at one point, meaning to suggest that we leave our drinks unfinished and head back to my place. But that wasn’t what came out.

“I was molested when I was little. I don’t think it damaged me or anything, but I just thought you should know.”

The abuse was on my mind because a visit with a relative had stirred up old memories, but Mark wasn’t the first person I had told, nor the first boyfriend. Those other men had been sympathetic, but they’d also left me with the feeling that I’d been broken, and that the cracks showed through the repairs. One of them expressed anger larger than I felt.

Mark reacted differently.

“Should we stop?” His tone was kind but also light—it bespoke no preconceptions.

“No!” I said.

In our first year together, he continued to show a nonjudgmental openness when I filled him in on my past and we analyzed why I might have blurted out my disclosure at a big romantic juncture. This helped me to work out my own feelings about the abuse rather than reacting to others’, something I’d struggled with through the years.

Now, raising two kids in a house we’d bought and rehabbed together, I wanted to know what he thought about the way I’d written about our younger selves. And what about the ways I’d written about our foray into parenting, and our son and daughter? I trusted his perspective on this above any one else’s, but that summer I replaced the manuscript on his dresser with one revised in light of my writer’s groups comments, and the following winter with a third revision that I was sending out to agents. They remained untouched.

I did not quit asking him to read it, in tones ranging from cheerful to plaintive to bitter. He’d answer with vague excuses, and each time he pledged to get to it soon.

We’d been together for nearly 20 years at this point. Most of the things that troubled each of us about the other we’d either been able to work on or adapt to until it was possible to joke about them. But this was one of those cases that can alter the geography of a marriage, a collision of tectonic plates that creates a mountain range. Mark was supportive in other ways related to the memoir—helping me find time to write, comforting me when strong emotions arose. But I couldn’t stop wanting him to read the book, and he continued to tacitly refuse.

The stalemate lasted long enough to see us reach a less intense phase of child rearing. Our oldest child began to walk or bike himself to school and rehearsals. Our youngest child was spending more time at friends’ homes. One afternoon when Mark and I were alone, I framed the issue in terms of the general health of our relationship, saying that I couldn’t imagine bridging the growing distance between us if he wouldn’t read my book. Finally he offered me a frank answer about why he hadn’t finished it.

“I’ve started it four times. I can’t get past page 60. It’s just too painful for me to read.”

When pressed, he admitted it wasn’t just the scene of sexual abuse that was difficult for him, it was also a scene of good sex with a boyfriend I’d traveled with when I was 20.

At least this was something specific we could talk about, and we even had the opportunity. But the conversation didn’t break our impasse. Not only did I have trouble accepting his response—he’d known about the specifics of the abuse, and our relationship had not been marked by jealous backward glances. But I couldn’t understand how two early scenes, even if troubling, could prevent him from continuing on when he knew the book was larger in scope, as well as so important to me.

He vowed to try again, but I didn’t believe he would. Meanwhile, I had found an agent, but we were receiving rejections from the big publishing houses, who admired the writing but were worried about the topic from a marketing perspective. I felt dejected. If even my husband couldn’t handle it, could I blame them?

I also grew embarrassed. Plenty of my writer friends had partners who were their first readers, and I developed a knack for zooming in on the lines in acknowledgements pages that praised spouses who’d read every word of the manuscript again and again—as Mark had done with my first novel. It’s one thing to know you shouldn’t compare your marriage to other people’s marriages, and it’s another not to do it—especially when you’re feeling insecure.

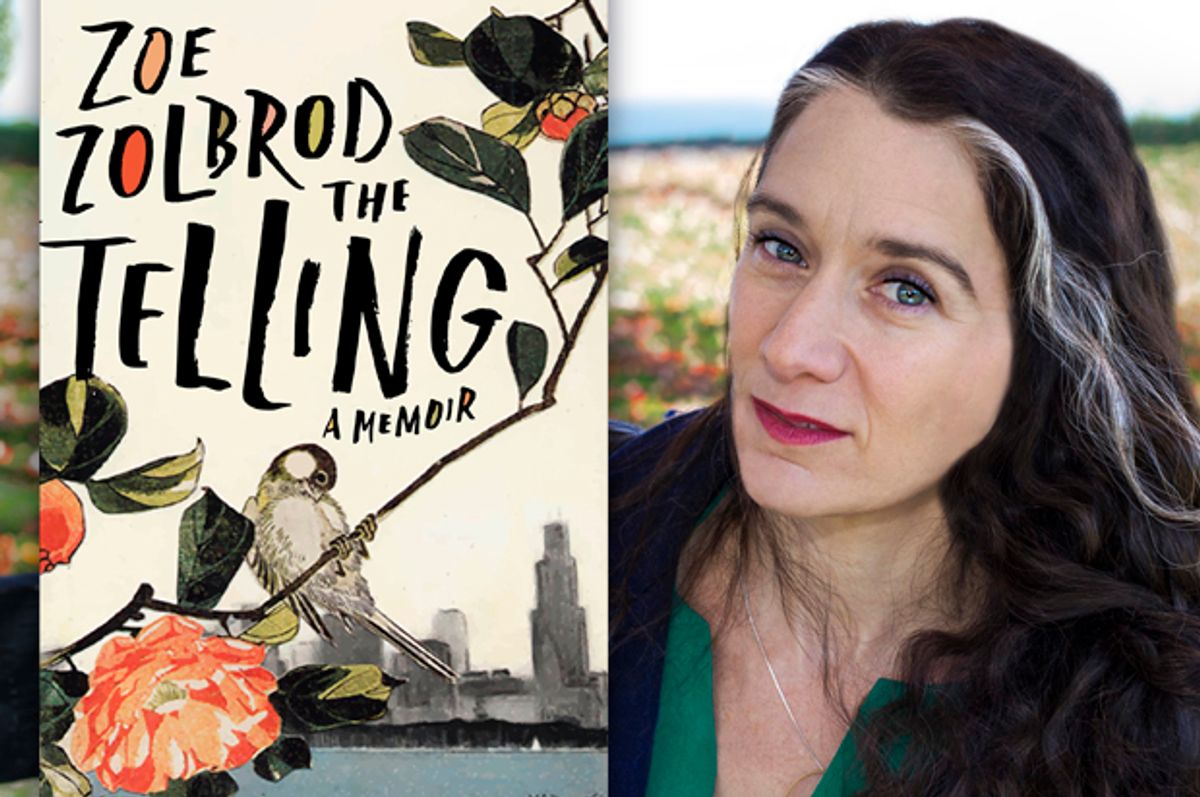

When the book sold, the designer asked for my input on cover images. Mark and I looked through his artwork together, discussing each piece in terms of the theme and mood of the book. I felt a pang that I had to explain so much to him, but also pleasure in seeing him gain a spark from my ideas. We submitted several pieces. The publisher chose one titled “Love Poem: Chicago.” It was a collage built around a photograph Mark had taken of the skyline as seen from the spot on the lakeshore where we used to bask.

At a dinner, when Mark’s new employer asked whether Mark read my writing, I could feel him stiffen beside me. I was able to take his arm and say he’d not read this latest book, but that it was his image on the cover. We looked at each other and smiled—an old married pair communicating a long history in a glance. Maybe I was going to be able to accept this state of affairs after all. I wasn’t sure whether eventually finding a way to joke about it would be a sign of our relationship’s weakness or its strength.

The advance readers copies came, and they began to be distributed to early readers and potential reviewers, who often remarked upon the beautiful cover.

“I better read this!” Mark said emphatically one day, as if he’d just realized Christmas was upon him and he hadn’t gone shopping. I started to see him lying diagonally across our bed, leaving other things undone while he was propped on his elbows reading my book.

We were in the kitchen making dinner when he told me he’d finished it. He was enthusiastic, and wanted to talk. At first, I felt shy. My hands went cold around my wine glass, and I found it hard to reply. Was he being sincere? But our conversation became natural. We were cut off when our son came in the door, full of things he had to tell us right away. But that felt okay. I knew that later, there’d be time to continue what we’d started.

Shares