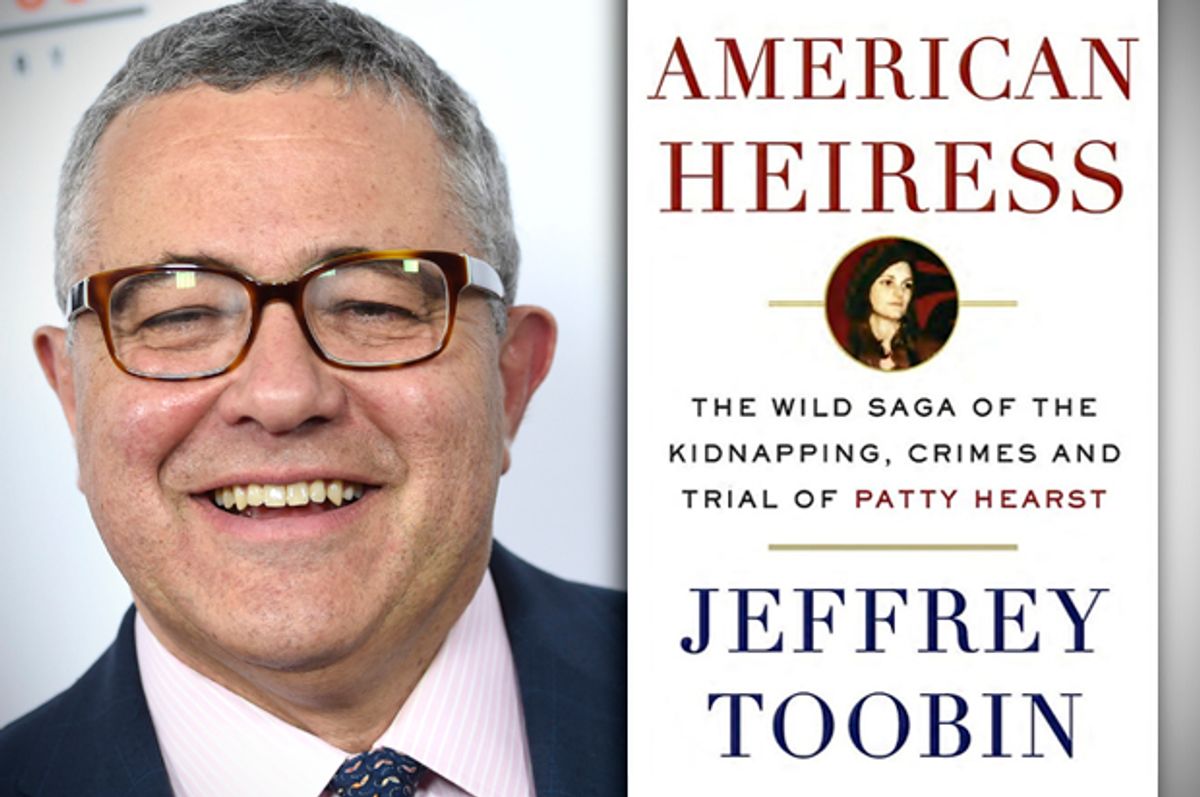

Author and journalist Jeffrey Toobin has written books on a broad range of topics: the Supreme Court, the Bill Clinton sex scandal and even the O.J. Simpson trial. (The latter book served the inspiration for the FX show “The People v. O.J. Simpson,” released earlier this year.) His latest book is a look at one of the stranger chapters in American history, the kidnapping and radicalization of Patricia Hearst. In “American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst,” Toobin has taken a look at not just the mystery of Hearst's conversion from socialite daughter in a famous family to gun-toting political radical, but also what this story really says about the political culture of the 1970s.

I spoke with Toobin by phone about Hearst's strange story. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You’ve written about all sorts of different things in your career. What drew you to writing about the Patty Hearst case?

It was a sort of strange but direct route. I did a piece for The New Yorker about three years ago, about this jail in Baltimore that had been taken over by a gang called the Black Guerrilla Family. And I got interested in the history of the gang, which, it turned out, was founded in Soledad prison by the famous prisoner George Jackson.

I got interested in this period when there [was a] tremendous amount of political activism in the California prisons. The Symbionese Liberation Army was born of that ferment, so I sort of came to it through the SLA.

My editor at Doubleday actually suggested Patty Hearst and I said to him, "Well there must be a million books about Patty Hearst," and he said, "Go check."

And I actually went and checked and I saw no journalist had looked into any of this in more than 30 years. So I thought, What the heck! It seemed like a good subject and I started doing what a journalist does. I started trying to track down sources and it turns out there were a lot of people who would talk to me about it.

Did you talk to Patty Hearst about it?

I did not. I tried. If you have the book in front of you, there’s an author's note at the end, which discusses this at greater length. She refused to talk to me and I tried everything, directly and indirectly.

She basically didn’t want to talk to me for two reasons. One is she’s in her early 60s now. This is very far in the past. She doesn’t want to relive the experience and I certainly want to respect that.

The other reason though . . . She’s given many interviews about this subject, almost exclusively to journalists who know almost nothing about the underlying facts and, I think, she didn’t really want to answer any sort of detailed questions because there’s a lot that, I think, is pretty hard to explain.

The thing I find interesting about your take on this case is you really have a 21st-century, feminist-tinged take on the whole thing, which is you cast Hearst as a survivor.

I’m so glad to hear you say that because I was intensely aware of the gender dynamics of the whole case. And as someone who was raised by a pioneering feminist, my mother, and I consider myself a feminist, I wanted to make sure that I told that part of it appropriately. Especially when you consider one of Patty Hearst’s claims from the very beginning has been that she was raped when she was kidnapped. I have been trained to consider those kinds of claims with great respect and seriousness.

The SLA itself was kind of a matriarchy. There were more women than men in it and they were all committed feminists. So the intersection of those competing views was something that I struggled to deal with fairly.

The debate about Patty Hearst since this all happened has been whether or not she was brainwashed or whether or not she went along with it and then lied about it afterwards. You fall somewhere in the middle.

To be honest, I am more in the latter camp. I think she was an active and volunteer member of the SLA for a great deal of the year and a half she was on the run.

I try to avoid in the book the buzzwords that are associated with the case: brainwashing and Stockholm syndrome, which are journalistic terms more than medical terms. Brainwashing in particular is a concept that came out of the Korean War where there were these prisoners in North Korea who were actively indoctrinated when they were taken prisoner.

The SLA was way too incompetent and disorganized to undertake a systematic attempt to brainwash Patricia Hearst. What they did was they talked to her about what they were doing and they gave her their perspective. [As was true for] other women in the SLA, who all came from middle-class backgrounds and most of them were cheerleaders, it’s unlikely that she would embrace what they said. But I think she did. Lots of people in the ’70s were embracing lunatic causes and I think Patty Hearst did, too.

You lay out a case for why someone like her would feel alienated despite having grown up in the lap of privilege. Why is that?

This is where the feminist movement of the early ’70s was significant. Here she was 19 years old. She gets engaged to this guy who is quite obviously a jerk, especially to her. She’s alienated from her mother who is this extremely conservative Southern belle who’s horrified that Patricia’s living in sin. And she’s starting to be aware of the rising feminist consciousness of people around her.

This combination makes her uniquely receptive [to] what she sees [coming] from the SLA. There were a lot of people who were receptive to these sorts of appeals in this era. Rather than use the term brainwash, my take is that she behaved rationally. She responded rationally to the bizarre circumstances in which she was placed. Likewise when she gets arrested, she responds rationally and says, to hell with this revolutionary bullshit. I want to go back to being a rich lady again.

That’s a very rational point of view.

She’s sitting there, having been on the run, where they have so little money that they’re sleeping under buildings at times, where they’re actually eating horse meat at times. And she goes to jail, and her best friend tells her, “It’s great to see you, but I’m going to Switzerland to ski for a month." Skiing for a month beats eating horse meat as a way to live your life. And I think in a very way rational way, she says to hell with this revolutionary bullshit.

That’s interesting because Patty Hearst gets talked about in this way that sort of singles her out as a unique and strange case. But in fact, the context for this is that that kind of radical leftism was widespread but short-lived. Can you talk some about the larger context there?

One of the things that was really interesting to me as someone who was alive in the ’70s but a kid and certainly not politically aware is that I knew the ’60s were a time of incredible tumult and assassinations and protests. And I had this background assumption that things chilled out. But I could not have been more wrong.

The ’70s were an angry and violent time. There was a smaller core of this counterculture, but it was a much more violent and angry core.

The statistic that sticks with me from the book is there were a 1,000 political bombings in the United States every year in the early ’70s. Think about what that would be like today. These were violent, angry times and there were hundreds, if not thousands, of people who were part of this movement.

So yes, it was aberrational in the larger scheme of American life. But there were lots of people in the hundreds, if not thousands, who were involved with revolutionary activity during the early ’70s. The SLA was a small part of it but there were other people doing it, too.

Some are in jail and some are college professors now.

One of the tragedies of the shootout that killed six of them in LA is that the odds are most, if not all of them, I’m pretty sure, would have drifted away from this insanity in the way that [SLA members] Bill and Emily Harris have drifted away from this insanity. Bill Harris became a private investigator and a good one. Emily Harris became a computer consultant and works for motion picture companies in LA.

It’s part of the aging process. You don’t see many 40- and 50-year-olds blowing up buildings. This was the spasm of violence. But had [some SLA members] not died [in a bank robbery], they probably would have served prison terms, as they should have, but they would have become reasonable members of society.

What do you think all of this says about the ’70s ultimately? Why did this happen?

That’s the question I spent a lot of time thinking about. To a degree, I didn’t realize this country was on the brink of a collective nervous breakdown in the 1970s. It was not just that there was a 1,000 bombings a year. It was also Watergate. It was also the energy crisis. It was also the persistent bad economy.

It really was a dark time in America, in many respects. The ’60s had violence as well, but there was this overlay in the ’60s of hope and idealism: You could have a Civil Rights Act. You could have a Voting Rights Act.

In the ’70s, that overlay of hopefulness had largely vanished. The darkness and dangerousness of the ’70s is really one of the most striking things for me in the book.

Shares