Thirty years ago, two things happened.

An aging musician, whose last album had bombed and whose taste seemed to belong to the past, dug enthusiastically into a musical form that few Americans knew about and made it almost instantly popular. Musicians associated with it found themselves with healthy international careers, and the music became a kind of soundtrack as a pernicious regime weakened and then fell.

Around the same time, a wealthy white American man broke a United Nations boycott designed to isolate a brutally racist government. He recorded an album in a black musical style that thrives overseas but was not known to Americans. When a huge corporation packaged it for Stateside consumption, the white man and his corporation became even richer. When most people talked about this musical style, they discussed the American man who had begun listening to it fairly recently, not the artists who had dedicated their lives to it. It was a classic example of whitewashing and the "white savior" phenomenon.

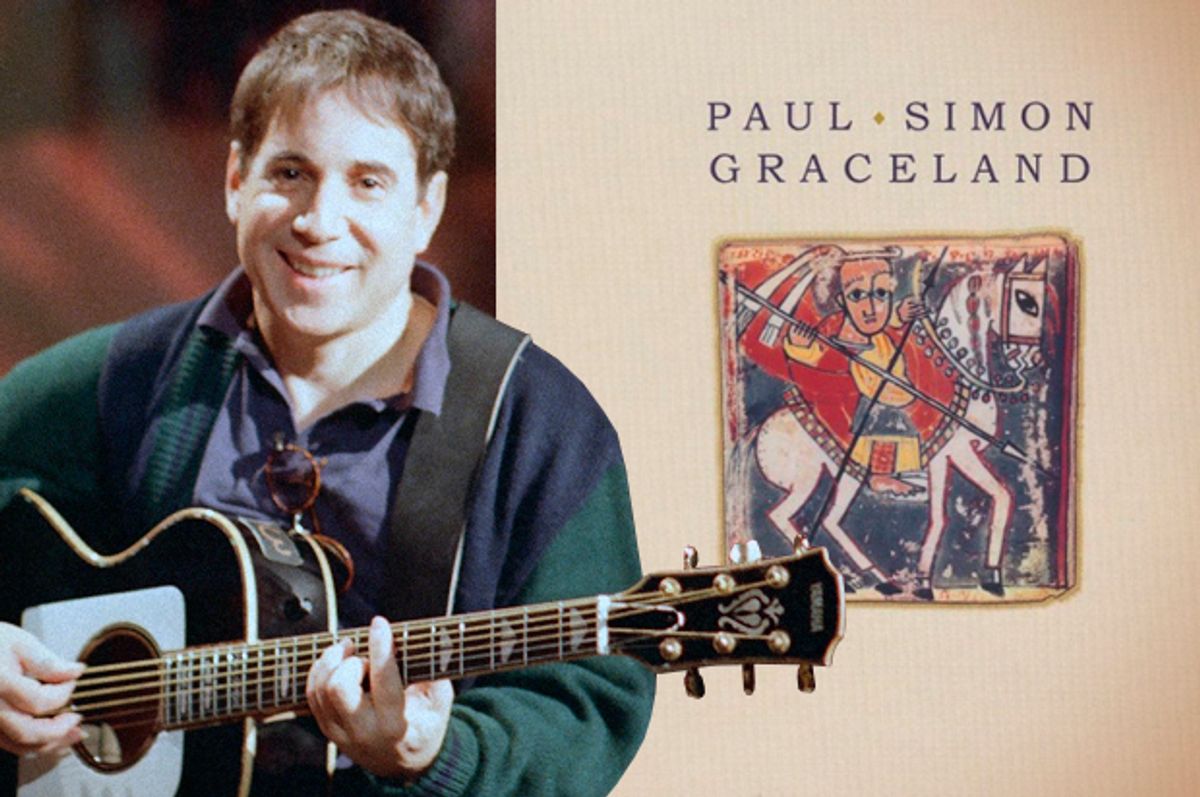

Of course, these two chronologies really describe the same event: the making of the Paul Simon album “Graceland,” which came out 30 years ago this week, incorporating a form of the music called township jive developed by black city-dwelling South Africans.

Over the years the album has been fraught for all kinds of reasons, though the nature of the criticism has changed a bit. It’s also critically revered, one of the most popular albums ever recorded in a non-Anglo-American style and genuinely loved by all kinds of people.

Today people tend to have complex takes on the album and its legacy.

“What’s interesting about this collaboration is that it’s this real syncretic thing,” said Aaron Bady, a scholar of African literature who writes widely on African music. “It’s not just ‘Paul Simon the folksinger, with a bunch of African musicians' backing him up.” Simon’s album, for all its faults, came out out a genuine curiosity about Johannesburg’s township jive. It may be naive in a “look what I found on my vacation” kind of way, but it’s not deliberately exploitative, he said.

While American cultural critic Touré, author of "Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means To Be Black Now" and "I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon," is well aware of all the racial and political complications around “Graceland,” he told me he loves the album. And Teju Cole, the American-born, Nigerian-raised writer and photographer, wrote this week that while breaking a boycott against South Africa was “a highly fucked up and selfish move,” the the album that came out of it is “great.”

So what happened?

In the mid-'80s, Simon was at a strange point. His onstage reunion with Art Garfunkel had started strong but then foundered. Instead of recording a new album together, Simon ended up removing all of his old partner’s notes from the ensuing “Hearts and Bones,” which sold poorly and received almost no radio play. His marriage to Carrie Fisher lasted only a year. But in 1984, he began listening to a cassette in his car by the Boyoyo Boys, a group that made accordion-driven township jive, a melange of a style that thrived in Johannesburg’s slums. Intrigued, Simon began writing and eventually headed to South Africa to record with some musicians upon the introduction of a local record producer.

Though it’s recalled as an album of township jive, the sound of “Graceland” also included zydeco, the traditional Zulu vocal music of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, jazz-influenced rock and Mexican-American styles. (Members of Los Lobos played on the album’s final track.) In many cases, the rhythm tracks were worked out and recorded first, in an improvisational process with the other musicians, giving it a very different feel than Simon’s other music.

At the time, township jive had little presence in the U.S., though the compilation “The Indestructible Beat of Soweto,” released in 1985, had developed a cult following, and Robert Christgau of the Village Voice had begun writing enthusiastically about African music. A few American musicians — Joni Mitchell, Talking Heads — had worked with African rhythms, but it was hardly a mainstream move.

Despite the low expectations that Warner Bros., Simon’s label, had for his project, the album became a significant hit, topping the Voice’s annual critics poll and selling 5 millions copies. Songs like “Diamonds on the Souls of Her Shoes” and “You Can Call Me Al” got significant radio play. And a handful of South African musicians — Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba and the exile Hugh Masakela among them — toured the world with Simon, saw their profiles bolstered, or both. Christgau called the album the real thing. (“Opposed though I am to universalist humanism, this is a pretty damn universal record.”)

Criticism festered alongside the praise. Simon’s breaking of the U.N. boycott against South Africa led Paul Weller, Billy Bragg and Jerry Dammers of the Specials to protest a London appearance. Others complained that Simon had the opportunity to sing about the evils of apartheid but instead released an album mostly about his feelings and apolitical topics. The contrast was apparent when Harry Belafonte (whom Simon had consulted over his mixed feelings about recording in South Africa) released an album of South African-inspired music, and his lyrics were unapologetically political.

The boycott and the horrors of the apartheid regime provided the context for the album three decades ago. If it had come out today, it would likely have been caught in the debate about cultural appropriation. While that critique goes back many decades, it’s become more central lately, with one of its most fierce and eloquent expressions delivered by actor and activist Jesse Williams at this year's BET Awards.

Williams’s speech — in which he spoke about “ghettoizing and demeaning our creations, then stealing them” — concerned American “whiteness” exploiting American black culture. But its critique applies equally well to musical colonialism. "So, it has taken another white man to discover my people?” South African musician David Defries told the Guardian in 2012 in response to the praise Simon had drawn for his South African excursion.

Bady said this criticism is not entirely fair when applied to Simon. “The blanket backlash against cultural appropriation is reductive and stupid,” he said. “That music is already deeply international.” Township jive, in particular, uses the pennywhistle, which had come from the British, and accordions, borrowed from the Dutch; American R&B had also shaped the music. “The world was already part of South Africa; this allowed South Africa to be part of the world.”

The ensuing years have brought a huge number of cross-cultural collaborations, with artists like David Byrne, Bela Fleck, Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal and Damon Albarn recording and collaborating with musicians in Africa, Latin America and elsewhere. They don’t entirely escape criticism, but musicians from the United States have tended to be respectful not just of the traditions they are venturing into but also the issues surrounding the partnerships.

“It’s basically just musicians making music,” Bady said. “Now ‘Graceland’ seems like the first of those albums rather than the last album of the apartheid era.”

Shares