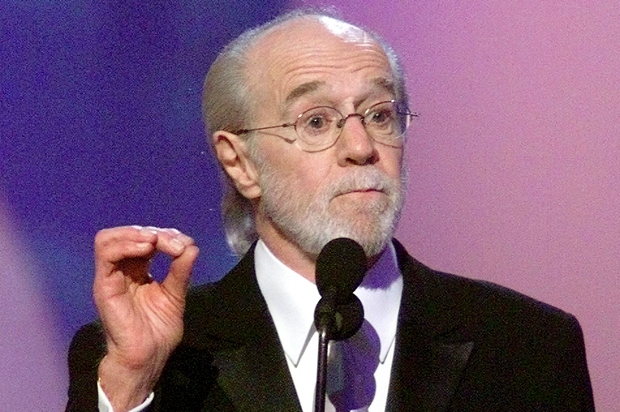

Eight years after his death, it’s easy to have warm feelings for George Carlin. However hard-edged some of his comedy was, he mostly seemed to rant with a humanist point of view underneath the cursing. Today he’s remembered as a hero of free speech — his famous “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” was not just an attempt to shock — and civil liberties. Late in his life, he became a gray eminence who acted in everything from Kevin Smith’s movies to “Cars” and “Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends.” He’s also a hero to some of the most prominent contemporary comedians, among them Chris Rock, Louis C.K., Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. No comedian from the past, besides maybe Richard Pryor, has more respect today than Carlin. (Judd Apatow has called Amy Schumer the Carlin of our time.)

If you’ve not listened to Carlin recently, the new album, which comes out on Sept. 16 (Sirius XM subscribers can stream it Thursday at 4 p.m. ET on channel 400 and 7 p.m. ET on 94) will offer a few surprises. The first is that despite Carlin’s association with the counterculture of the ’60s and ’70s, he was performing envelope-pushing material even earlier: It begins with his home-recorded “Boston Rant,” made in 1957 when he was only 20. He starts by greeting the listeners politely and then launches into a takedown of police and firefighters that would have been shocking in any era. “Firemen are pretty close to being as dishonest as the average dirty goddamn cop,” he says. “Your dirty, stupid policeman, who can’t even work at the A&P.” The voice is less gravely than that of the Carlin most people came to know, but the delivery and subject matter are there already.

Most of the rest of the album is derived from two shows in Las Vegas just before Sept. 11, 2001. Despite his warm-George film roles from his last two decades, the material is harsh: about drugs and toilet humor, griping about music and an ode to the pleasures of death and destruction. Oh, and did I mention that it’s called “I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die?” Some of the material was pulled or reworked because of the World Trade Center attacks, and it’s not hard to hear why.

All this material is delivered with force and discipline and perfectly polished. It’s also in almost every case nasty and disturbing. Much of Carlin’s work involved complaining: He hated organized religion, government in general, virtually all authority figures and people who misuse language. He makes BoJack Horseman sound like Oprah Winfrey.

By 2001, his crankiness had come to include the huge amount of music being released. There are too many songs, he said, and too many of them are love songs. “Everything’s a broken heart — fuck that, how about a punctured cheekbone?” By the time he starts suggesting songs about a fire at a crowded church or people suffering from cancer, it becomes clear that had he lived, he might have become one of the comedians uncomfortable with supposed political correctness. (In the disc’s liner notes, Lewis Black called the album “a perfect example of why honest comedy and political correctness always exist in parallel universes and have nothing to do with each other.”)

The most uncomfortable of these bits — and probably the most brilliant — is called “Uncle Dave” but it’s really about Carlin’s glee at mass destruction. Even Carlin probably did not have to think hard about whether it should have been released in the days after Sept. 11, 2001. Of the things he says he really likes, he lists “plane going down” among them. “To me, anything that kills a lot of people is exciting. . . . I’m always rooting for a really high death toll.”

He talks, too, about the pleasures of earthquakes, forest fires and other disasters that are currently a little too close for comfort, with recent news from Italy, California and elsewhere. “Come on,” he adds. “You can’t beat a famine.”

And if you are not into toilet humor — the recording includes pieces called “The Fecal Differential” and “The First Enema,” this might be one to skip.

The recording is also a reminder that while Carlin was primarily a man of the left, his mistrust of government put him closer than he would have probably admitted to the Idaho militias he makes fun of in one of his bits.

Overall in this posthumous release, Carlin is effective, intense and as disturbing as ever. It’s good to hear a voice so intelligent and raw. But it also feels good when he stops. Nobody said comedy was pretty.