“Stranger Things” is hotter than Kayne’s Twitter feed right now and Netflix just announced that a second season is on its way. A trailer recently posted online reveals that when 2017 arrives, fans pining for more '80s pop culture references will be returning to Hawkins, Indiana, in the fall of 1984 as the town faces the aftermath of its first contact with the alternate universe known as “the Upside Down” and the predatory "Demogorgons" that dwell therein. [Note: Spoilers ahead.]

Right now most reviews and discussions about “Stranger Things” focus on its aesthetics: how the Duffer brothers crafted such an eloquent piece of pastiche that takes the best elements of 1980s pop culture and reassembles them into something fresh and entertaining. Of course, that’s worthy of discussion in and of itself. Who wouldn’t jump at a chance to spot a “Goonies,” “Evil Dead” or “Stand By Me” reference and gush adoringly to their friends about it? But then again, there’s a lot of TV, music and film doing the same thing these days. So it’s worth asking — especially while we wait for the next season to arrive — if there is something more to “Stranger Things” that accounts for its popularity and the mass amounts of speculation surrounding its mysterious aura. I think the answer is yes, and I think that’s worth talking about, too.

Even by the end of the first episode, one gets the sense that the Duffer brothers are more than just writers and directors who have an extensive knowledge of '80s gold. They seem to be filmic philosophers who emerged out of the shadows with this series to deliver an intriguing commentary about a world like ours, a world rife with communication technologies that can harm us just as much as they can help us.

“Stranger Things” is set in small-town America in the 1980s. On the fringes of this town is a mysterious Department of Energy compound conducting weird experiments somehow related to the U.S. military and espionage. People are not really worried about this organization, though, until they have to start worrying about it because technology, espionage, militarism, fear, surveillance and such things were all staples of the Cold War era. (But, in fact, without the Cold War, much of the technology we have today — like the internet and personal computers — simply wouldn’t exist.)

But then all of a sudden the worst thing happens that could possibly happen to a mother, older brother and a small community. A young boy is stolen away in the night to . . . where exactly? Will Byers, like other characters both major and minor in the show — #TeamBarb! — has been kidnapped and possibly eaten by a predatory creature that his friends have dubbed the Demogorgon, after a monster in their Dungeons & Dragons game. The Demogorgon travels through numerous gates between our world and another dimension — the Upside Down — that is sort of like our world but way darker and scarier. The alternate dimension and the Demogorgon are somehow connected to electricity, wires, appliances and communication devices. And they all go nuts whenever the monster lurks about in the real world.

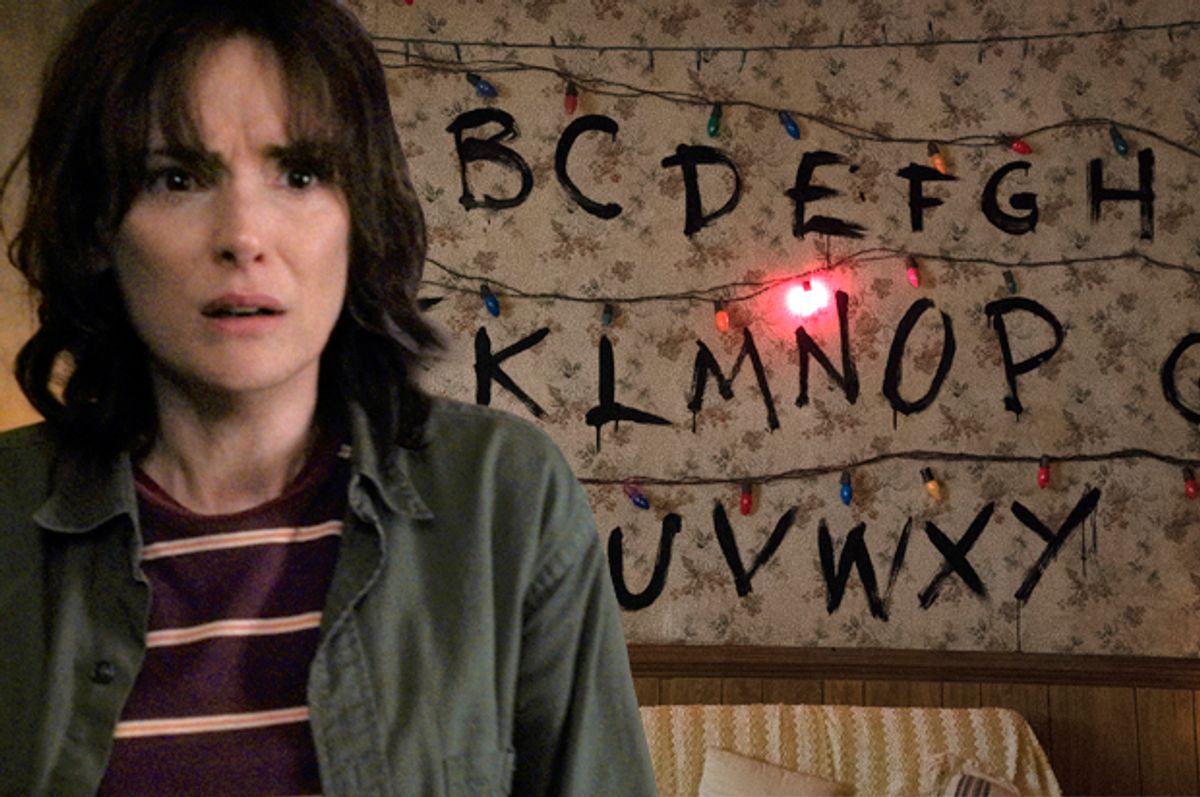

Likewise, people trapped in the Upside Down can reach the real world only through electronic devices like telephones and radios, and the bigger the device, the better the contact. We see this clearly when Will’s mom Joyce (Winona Ryder) creates a primitive codex-like thing by painting a wall with the alphabet and assigning a light to each letter, which allows her to use it as a keyboard to communicate between dimensions with her missing son. She asks questions and Will spells out answers by flashing lights above the appropriate letters. It seems like magic, but it’s just primitive computing technology.

All of this sounds like the foundations of the internet, doesn’t it? A network of electricity, phone lines, communication devices and flashing lights that work together to connect distant worlds so that disconnected people can meet and dialogue with each other. I would wager that this intriguing little detail represents a key theme in “Stranger Things.” It also explains why the show has become so popular. Just like now, the '80s was a paradoxical time of both hope in technology and fear of it. Deep into the Cold War by 1983, both the East and West knew that technological development was both their biggest threat and their biggest hope.

The race to space known as Star Wars — Reagan’s missile defense program, not the films — and the mass ramping up of innovations in personal computing, information technologies, communication devices and consumer entertainment systems, all combined to simultaneously strike people dumb with awe and cower in fear. Sure, an atomic bomb could hit a town at any moment and a commie spy could be running a local grocery store, but at least people had some newfangled digital devices and entertainment while they waited for all that horrible stuff to go down. Meanwhile, the military would be using all this technology to gain the upper hand on the enemy.

All of this explains why the Demogorgon and the sinister Department of Energy lab are secondary issues in “Stranger Things.” The primary issue is the Upside Down, the alternate dimension that the Department of Energy accidentally discovers. If this gate had not been opened up by Eleven, a mysterious child with telepathic and kinetic gifts who is forced to go into that world and inadvertently make contact with the Demogorgon, the monster would have never shown up in Hawkins to kidnap people in the first place. So it’s the Demogorgon’s network, the world it lives in and connects to, that enables the monster to be anywhere at any time to snatch poor Will and Barb away to the Upside Down. That is the real threat to everyone in Hawkins.

Which is to say, the Upside Down starts looking very much like an analog for the internet. Yes, the internet allows people to connect everywhere at every time, but this is not always a good thing. Just look at Kayne’s Twitter feed. Or, on a more serious note, consider the devastating social-media harassment campaign that has targeted actress Leslie Jones. Or reflect on the degree to which even our most banal online activities and conversations are being watched and collected by government agencies.

This explains why there are more seasons to come because by the end of the first season, it appears that the Demogorgon is dead. But the network itself, as well as its effects, remains. Will Byers might be back in the real world to go on D&D quests with his buddies and be bullied at school, yet the network has made an impression on him that he can’t shed. Now he is a part of the Upside Down network and he’s brought it back to Hawkins. We see this when he coughs up a little Demogorgon slug in the concluding episode. The network and its demons are taking root and growing. Pikachu is in our world now and we’d better watch out.

Once you start pulling at these thematic threads, you begin to see a deeper philosophical discussion at play in “Stranger Things.” Of course, some fans love this show because it captures several of their favorite memories of the '80s. But at the same time, and perhaps more important, we’re intrigued by the experience of watching characters in “Stranger Things” encounter the consequences of rapid technological advancement.

There’s no better example of this than the scene when Joyce Byers finally makes semi-physical contact with Will through an opaque window that appears behind the wallpaper in the Byers’ living room. For a glimmering moment Joyce is able to reach out to Will through a translucent screen to see that he’s alive. And Will reaches back. But that window evaporates as quickly as it appeared. So Joyce takes an ax to the wall to break through to the young Will trapped in the Upside Down. She chops right through the wall and finds . . . nothing — just the world outside. Will is gone. The network escapes Joyce’s grasp, her son is still kidnapped and her life is still in shambles.

It turns out that technology can’t bring Will back, only humans can. And humans eventually do. This draws out a key thesis of the show: We don’t need more or better technology to solve our greatest problems. What we need is more courageous people — like Joyce and Sheriff Hopper; Elle; Will’s friends Mike, Lucas and Dustin; Will’s brother Jonathan, Mike’s sister Nancy and (eventually) her boyfriend Steve.

It may be difficult for some younger viewers to think about what the world was like before digital technology and the internet arrived on the scene and developed into what it is and does to us today. But artistically and philosophically “Stranger Things” helps fans get to (or back to, depending on the viewers' age) that place. And once we’re there, we’re pressed to explore ethical questions similar to those encountered by the kids and adults of Hawkins. Will we or won’t we make contact with the Upside Down and dimensions and technologies of that kind? And if we do, how will we act when things get strange, volatile and perhaps even violent?

Shares