On Dec. 4, 2000, Salon ran a story by investigative journalist Greg Palast that added a whole new dimension to the controversy over the election in Florida — a premeditated, racially skewed effort to purge 173,000 likely Democratic voters from the rolls.

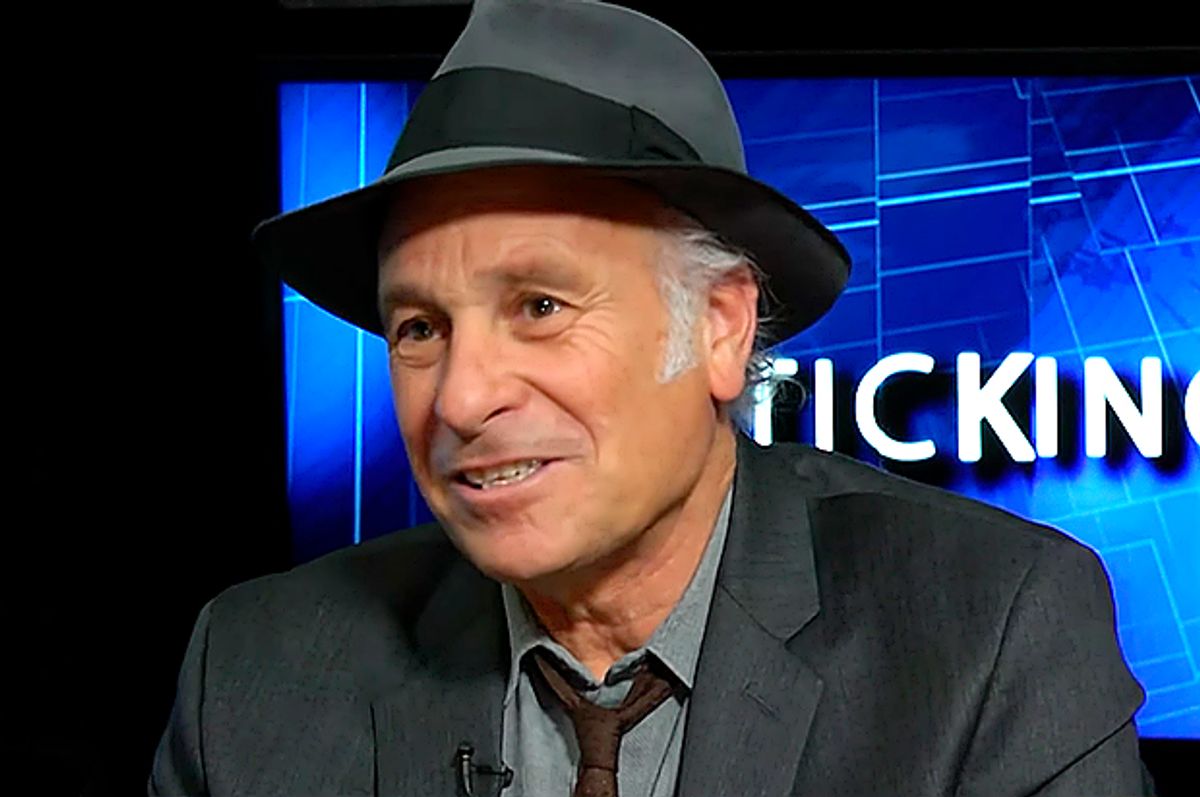

“We broke the story that Jim Crow was back but now he was Dr. James Crow, cyber analyst, using computers to conduct a lynching by laptop,” Palast told Salon, almost 16 years later. Since then, it's only grown “more sophisticated, wider, nastier, bigger,” he said. He's been on the story repeatedly ever since — most recently in Rolling Stone — and is about to release a noir-detective-themed documentary, "The Best Democracy Money Can Buy," bringing the story up-to-date later this month.

"I wanted to give people the whole arc of the story," Palast said, "so I have the Salon story done in cartoon form, Saturday-morning-cartoon-style, by the guy who did Who Framed Roger Rabbit." But as compelling as the vote-stealing issue may be, there's an even deeper story going on. "It's not about the Republicans stealing the vote," he said. "It's about billionaires stealing the treasury."

Money is definitely driving the story, as Palast's investigation reveals, but the two are intimately inter-connected through a wide range of figures, including the Koch brothers, Karl Rove and Kansas Secretary of State Chris Kobach. Either side of the story can get dizzyingly complex — that's part of how they pull it off — so the film brings narrative simplicity, or at least, coherence, by making it about the who-dunnit discovery process itself.

"This is the story of the investigation of the theft of the 2016 election — it's a crime still in progress — and a hunt for the very rich guys behind the crime," Palast explains at the beginning. So when Ice-T and Richard Belzer from SVU (Special Voter Unit) pop in for a couple of cameos, they fit in seamlessly, as does a commando-style approach to crashing a swank affair to ambush-interview a billionaire. But it all starts off with the GOP's outrageous voter fraud claims catching Palast's eye.

Palast watches Dick Morris's 2014 on-air claim that over 35,000 people had voted in North Carolina and in some other state, and his accusations that "You're talking about probably more than a million people that voted twice in this election," which Morris claimed was "the first concrete evidence we've ever had of massive voter fraud."

"A million double voters? Really, Dick?," Palast asks, incredulous. "You vote twice, you get five years in the slammer."

It's followed up Donald Trump's claims of people "voting many, many times."

"Really, Donald? A double-voting crime wave?" You can hear the incredulity deepening in Palast's tone. "Is there really a gigantic conspiracy of one million Democrats to vote twice, or is it a massive scheme to take away the votes of a million innocent people?"

He had to get his hands on the list of "skanky double-voting fiends" to see for himself. And so he called officials in North Carolina, asking for the list of names — from the interstate "Crosscheck" program spearheaded by Chis Kobach — but he got the brush-off. Undeterred, he called officials in 28 other states, and was told repeatedly that the Crosscheck list of supposed criminals was "confidential." Finally a secret source provided the list of 7.2 million suspects in 29 states.

But as the list scans slowly up the screen, one thing immediately jumps out: The first names and last names may match, but the middle ones don't. There's "George Joseph Peck" matched with "George R. Peck," "William Trad Price" matched with "William E. Price," "Angela L. Reeves" matched with "Angela Kay Reeves." The list goes on and on like that.

This is where the 2000 flashback comes in, providing the template for everything we're seeing today in various, more sophisticated forms. "Ex-cons willing to go back to prison just for voting?" That was Palast's original incredulous response back in 2000. Sure enough, after beating the bushes, "I couldn't find a single illegal voter."

Eventually, someone slipped him a copy of the Florida list, but the names didn't match up. Jonathan L. Barber lost his right to vote, because he "matched" the felon Vincent Barbieri. On top of that, their birthdays didn't match. Nor did their races: The felon was white, the voter, black.

Worse than that, Palast notes, "Some of these criminals were convicted in the future." Take that, Philip K. Dick! 2021, 2025, 2035, 2040, 2050, 2071, 2099, 2187, 2805! Others had no conviction dates listed at all.

The number of real felons Palast could find? “Zero. Nada. Bupkis.” But not for lack of trying. And he tried again, years later, when he got his hands on the Crosscheck list. Finally, he had a lead! One character showed up voting 14 times — "He's even got his own bus to vote in several states at once," Palast notes: once as Willie May Nelson in Georgia and again as Willie J. Nelson in Mississippi.

"The first time you voted as a woman, is that why the pigtail thing?" Palast asks the country music legend. "Yeah," Nelson hurriedly agrees. "What are you grinning for, are you smoking something?" Palast asks. "Aren't you?" Nelson shoots back. "It sounds like you got better shit than I got."

Altogether, Palast's team found 2,000,000 middle names that don't match.

Crosscheck's PowerPoint presentation says they use Social Security numbers and birthdates, but the lists contain neither. "They don't want to capture double voters," Palast concludes. "It's just a bunch of common names." And why not? As the film later states, 90% of all Washingtons are black, 94% of Kims are Asian, and 91% of Garcias are Hispanic.

But it's not as if double-voters couldn't be found, if that were really the point. The Koch brothers are partial owners of i360, which has a highly sophisticated database, and is being constantly refined for GOP election work. It includes “trillions of data-points on hundreds of millions of people," data analyst Mark Swedlund tells Palast.

"With all that computer power, couldn't the Kochs and Rove find real double voters?" Palast asks.

"You could do that in a heartbeat." Swedland responds. "I would argue it would be a piece of cake."

In contrast, the Crosscheck system was "incredibly simplistic," Swedland said, a "childish methodology." In fact, it seems custom-made to produce garbage results, the better to bury unwanted voters with.

But that's only one part of the story Palast is after — the data part of the "how" side of voter suppression. There's also the very human side of how it plays out, the myriad other obstacles thrown together to help block unwanted voters — primarily black, Hispanic and Asian — from exercising their right to vote. But above all, there's the "why" side as well — the money reasons driving the Kochs and others allied with them. “There's no such thing as a victimless billionaire,” Palast explains.

That side of the story takes him all the way to the edge of the Arctic Sea, and all the way back to the mid-'90s, when the Kochs faced hundreds of charges for their environmental crimes. Pulling all the different strands together is a wild and woolly ride, peppered with moments of wry sardonic humor that would make Dashiell Hammett smile. There's so much more I'd love to tell you about what Palast dug up. But then I'd have to kill you. So you'll just have to see "The Best Democracy Money Can Buy" for yourself.

Shares