Another NFL season is underway and Commissioner Roger Goodell, operating for the moment without the adjectival modifier “embattled,” has decided that the best defense is a good offense.

Earlier this week, he announced that the league would spend $100 million to research head injuries and develop new technology.

One hundred million dollars is a lot of money. But a little context might help to put this largesse into perspective.

First, the league just shelled out an estimated billion dollars to settle a class-action suit filed by 5,000 former players. These plaintiffs accused the NFL of not only negligence but fraud, a “concerted effort of deception and denial” in the matter of head injuries, one that included “industry-funded and falsified research.”

Second, the NFL raked in an estimated $13 billion last season, and Goodell has said that he hopes to goose annual profits to $25 billion by 2027.

One hundred million dollars is still a lot of money. But it’s a tiny fraction of what America’s most popular and profitable sports league nets annually.

More to the point: There is no pile of money big enough to stop NFL players from winding up with brain damage. Because no pile of money can undo the basic physics and physiology of the game.

Here’s how the physics work: Mass times acceleration equals force. Today’s football players are bigger and stronger and faster at every level of the game. Thus, every time they collide (which is almost every single play, whether in games or practices) their brains are absorbing more force.

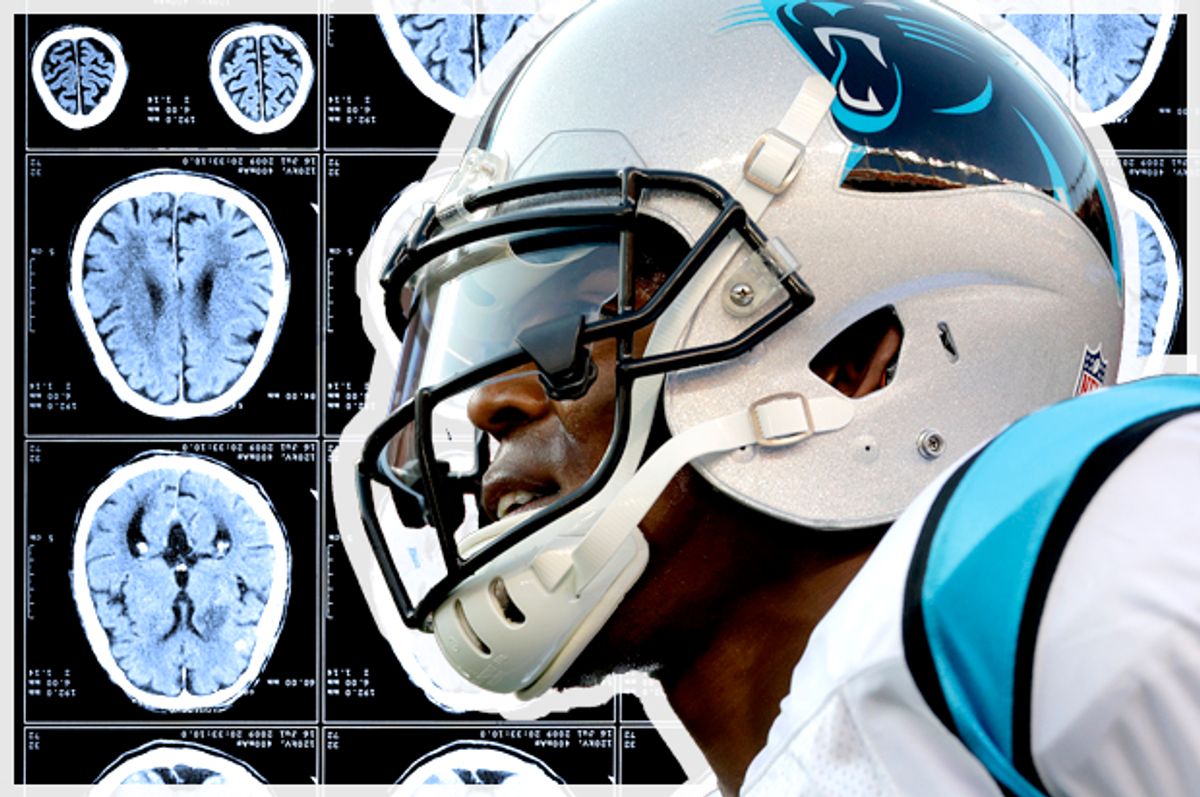

Here’s how the physiology works: The brain is a soft organ encased in the hard shell of the skull. Every time the brain hits the inside of the skull, it sustains tissue damage. Enough of this damage and you wind up with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease that causes depression, dementia and erratic behavior.

To date, CTE has been identified in 87 retired players, including Hall of Famers such as Frank Gifford, Ken Stabler, and Junior Seau, who took his own life.

Over the past decade, medical researchers have determined that the primary cause of CTE is not catastrophic hits to the head, of the sort star quarterback Cam Newton sustained last Sunday, for instance.

It’s the steady accretion of smaller hits that amass over the course of several years — those thousands of tiny car accidents that occur inside a player’s helmet and are invisible to the viewer, the player and the medical staff.

Limiting concussions certainly would help protect players. But to claim that the NFL faces a “concussion crisis” is misleading.

The fundamental problem is that football causes “long-term cognitive ailments” in a significant number of its players, “up to 30 percent” by the NFL’s own estimate. To put that more bluntly: The NFL projects that nearly a third of employees in their workplace will wind up with brain damage.

As evidence of these health risks has become increasingly incontrovertible, the dynamics of the issue have begun to ape the debate over global warming.

There are almost no serious medical professionals who deny the neurological dangers of football at this point. Instead, the pushback comes directly from those who work in, and profit by, the football industrial complex: owners, NFL executives, sports pundits and players.

The central effort is no longer to deny the link between football and brain damage. It is to distract fans from their own complicity by arguing, for instance, that players now know the risks and still choose to compete.

Of course, the players choose to compete because there are massive incentives — all of which redound to the fans.

The league’s promoters also talk, when pressed to defend the game, about how hard the league is working to make the game safer.

But the plain truth is that Goodell and his minions could virtually eliminate the health risks in football tomorrow. The problem is that doing so would require making the game less violent (two-hand touch, anyone?) and they would lose billions in proceeds if they did that.

The NFL’s only real option at this point is to throw money at the problem and hope that sways public opinion.

This is essentially the same mindset that governs the fossil fuel industry’s propagandists. They aren’t trying to deny that their products are harmful, or that global warming poses risks to the planet. They are trying to convince consumers that they are making an effort to find “clean energy solutions.”

In the case of global warming, Americans have an obvious incentive to change their patterns of consumption. Because we’re ultimately at risk. Every news report of a record-breaking heat wave, or a drought, or a wildfire, or a catastrophic weather event affirms this.

But the beauty of football, from the fan’s perspective, is that the players assume all the physical risk. The only incentive to stop watching is whatever tug of conscience you feel when a player suffers a gruesome injury.

The NFL’s latest outlay is aimed squarely at reducing that tug. If fans can point to new rules that reduce concussions, and new helmet technology, they can tell themselves that the league is “cleaning up the game.”

The ugly truth is that these measures will not prevent your favorite player from winding up with CTE, any more than your decision to drive a hybrid, or to recycle your plastic bottles, will stem the tide of global warming.

Roger Goodell and his coterie of public relations experts know this. Their $100 million outlay was never about finding a magic bullet. It was about building a better fig leaf.

Shares