"Wanting attention is genderless. It’s human," model Emily Ratajkowski wrote in a recent piece for Glamour that swiftly went viral. "Yet we view a man’s desire for attention as a natural instinct; with a woman, we label her a narcissist."

And boy, doesn't author Sady Doyle know it. The feminist writer's new book "Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear . . . and Why" explores this very double standard. Women who seek public attention, as Doyle has documented, can expect to have their sex lives, mental health and personal relationships picked apart in ways that men are generally spared. Men have sex, have messy personal lives and even have mental health problems, she has noted, but they still get to be portrayed as heroes and artists: See, for example, the legacies of Lou Reed, David Bowie, David Foster Wallace, Hugh Hefner and Miles Davis.

But women? Women with the same kind of lives — Amy Winehouse, Marilyn Monroe, Billie Holiday, Whitney Houston, Kim Kardashian — are regarded as train wrecks, moral lessons for other women about the supposed dangers of being in the public eye instead of staying at home. And this has been going on, as Doyle has documented, for centuries.

I spoke with Doyle about her new book and why feminists need to stand up for a woman's right to be as imperfect and flawed as our male counterparts. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

Quote from you: “Women who have succeed too well at becoming visible have always been penalized vigilantly and forcefully in public spectacles." Why is this?

There is an idea that women should not try to enter the public sphere at all, that women should be silent, that they should have mainly private lives. And that’s a way to keep women from exerting influence on the world. This is something that there have been actual laws passed into the books about.

But nowadays we can’t exactly say that it is illegal for a woman to vote or to run for public office or to speak too loudly and piss off the neighbors, which, believe it or not, was a gender-specific law back in the day.

What we can do is make visibility uniquely dangerous for women. You know, these women, whether they are doing things that you and I might consider serious — like running for public office or writing high literature — or whether they are doing things we might see as pop-cultural entertainment — releasing albums, showing up on TV shows — they are all marked as highly visible and, in some senses, uniquely successful women.

So what we do is we say, “Well you wanted us to look at you. Let’s see how much we can make you regret having our attention.” And that means that they are subject to uniquely invasive coverage of their bodies, whether that is upskirts or hackers leaking their nudes and sharing them around the internet. It means they are subjected to incredibly intense scrutiny of their personalities.

Nobody that has our attention for 24 hours a day is always going to be nice or always going to be perfect at all of their relationships or always going to behave in a totally dignified fashion. But we tend to find whatever flaws we can in these women, whether it is getting dumped or going to clubs a lot or being loud or insensitive or provocative in the way that they speak. And we blow that up until it becomes the entire narrative. It is more profitable and popular to scrutinize their personalities and their personal choices than it is to actually consume the work that they make.

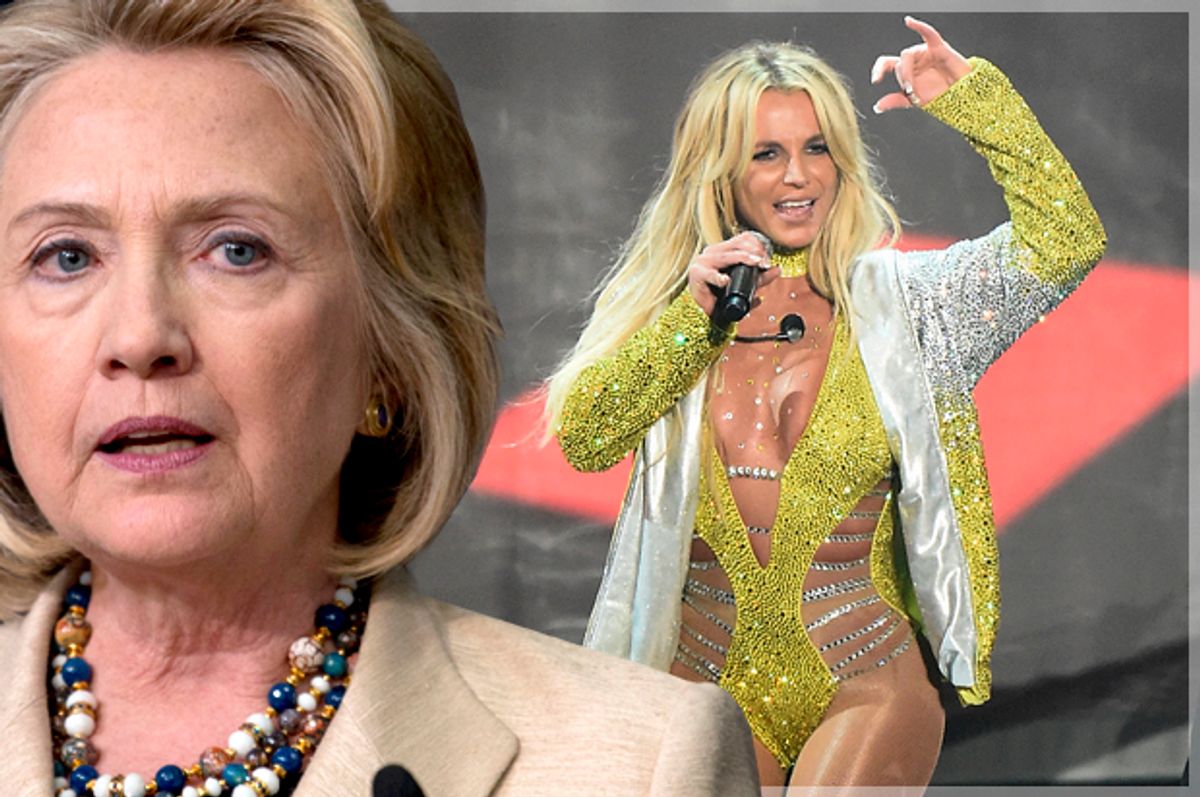

Your book covers women who get the “train wreck” treatment, from Britney Spears to Hillary Clinton. What do these two women have in common as far as how they are perceived in the public?

There are a lot of leaps in the book. I think my Paris Hilton to Mary Wollstonecraft is in the first chapter and I just thought, Well, if they can read past that connection, then maybe my crazy nonsense will maybe work for them.

I think that Hillary and Britney are interesting to me because they arose at the same moment; they arose out of each other. One of them was sort of demonized really intensely throughout the '90s for being old and for not being seen as sexy. There was a lot of nasty coverage.

For example, Bill Clinton’s infidelity focused on the idea that he sort of had to do it because his wife is so awful and so unlovable. She was very much stereotyped as the frigid, uptight, yuppie wife, you know, feminazi shrew — what have you.

At the same moment, we are starting to create perfect girls, and we wind up with someone like Britney Spears, who is really marketable for her ability to sell sex, and the specific porny sex as a teenager, while simultaneously claiming to be a virgin. You know, she had to be hypersexual in her image, while also staunchly denying having any sexual feelings whatsoever.

They both arose out of the debate over what a worthwhile woman would look like and specifically what the sexual politics of being a good woman were.

You know, you couldn’t be like Hillary. You couldn’t be this old, unsexy wife who thought she was so smart and wanted to work on health care. But you also couldn’t be young and dancing around in a bikini without people calling you a skank.

Monica Lewinsky is another one. You would think that if people hated Hillary so much, this woman who Bill Clinton had an affair with — we’d be sympathetic to her. But we weren’t. All of her press coverage was about how she was crazy and unstable and driven by her immense sexual appetite. She wore thongs and gave blow jobs. And what good woman would do such a thing?

So to have the three of them together, to realize that we had the prude and we had the quote unquote slut and then we had Britney, who simultaneously had to be both a Madonna and a whore. And all three of them were just loathed for doing that.

It shows that there is no escape outlet. There is no way you can actually do "being a woman" correctly in the public eye and not get people who just hate you and want you to shut up and go away forever.

Speaking of Mary Wollstonecraft, your book has a lot of historical examples of women getting the train wreck treatment. Like many of your readers, I thought of Mary Wollstonecraft as an 18th-century feminist philosopher and the mother of the woman who wrote "Frankenstein" and I hadn’t thought more past that. But in her day she was considered a train wreck. Why?

Mary Wollstonecraft's actual ideas are so common now. For the good Lord’s sake, one of her most controversial positions was that women should be able to learn botany! Which was a real debate back in the day because if you learned about botany, you were sort of indirectly learning that sex existed — like the plants were so suggestive that if we let our daughters know about all their plants parts, it would corrupt them forever.

So we can think of her as boring because who cares about whether women should learn botany. But she was in some senses very radical within the context of the 18th century.

She was specifically sexually radical. She did not believe in marriage. And she had two relationships, one of them very serious, a live-in relationship, without being married. That second relationship was with a man named Gilbert Imlay and, you know, to this day, historians are trying to figure [out] what she saw in him because he turned out to be a horrible person.

They have their daughter and they were in the middle of war-torn, revolutionary France. He left her with a newborn, did not tell her what was going on for months and months, and she kept writing to him like, “When are you coming back?” And he’s like, “Oh, in a minute. I have some business prospects to attend to. Don’t worry, I’ll be back.”

She began to become very depressed and very sort of unmoored. She took a dark turn and when she found out what had happened, which was that Imlay was living in London with another woman, she tried to commit suicide twice.

She eventually got married to a man who loved her so much that when she died, he chose to write a biography, and publish all of her letters. Every single scandalous thing about her sex life and or mental health was revealed all at once.

You cannot imagine what a gift that was to the right-wing press of the day. These guys, who were writing poems about botany and about how we’re turning our daughters into sluts by letting them study plant sex, they were able to point to it and say, “And you know who said your daughter should study botany? This woman, the woman with the illegitimate baby who tried to kill herself two times.”

She was called a maniac, an unsexed woman. The Anti-Jacobin Review, which was the real hard-core right-wing publication at the time, just straight up called her a whore and a usurping bitch. Her bad reputation lasted for a long time. It lasted for most of a century, until the beginning of the 20th century.

There is this train-wreck narrative that I think your readers are familiar with, that is pushed by TMZ and Perez Hilton and even in the mainstream media. But the audience for it is mostly female. It’s women more than men who are reading these blogs, who breathlessly follow every supposed heartbreak of Jennifer Anniston, etc. Why is this more of a women’s thing than a men’s thing, when it is so obviously sexist?

I don’t want to dump on people who are into gossip. I obviously would not have written an entire book about this if I weren’t fascinated by it and if I didn’t read it and consume it myself.

It is very much about policing femininity, finding women who are doing "femininity" wrong and humiliating them as a way to enforce social norms around what a good women is.

Women are taught to police their own femininity harshly all of their lives. Every day you wake up and you try to be a woman and you try not to do being a woman wrong. Women, more so than men, are taught to define their own value based on whether or not people like them.

We are constantly looking for some pressure-release valve. It is so easy to look at a woman who is clearly doing it quote unquote wrong: “Britney Spears has gained weight and she is stumbling around and why can’t she just get her life together.”

That feels good because you can look at that and say, “Well, at least I’m not her. At least I am doing my femininity a little bit better than she is.”

Another part of our fascination with these women, and potentially a really healthy part, is that they get to live out things like pain or heartbreak or just not being able to get it together on a certain day, when we are taught to hide and suppress that.

We can either look at them as a way to sort of pull ourselves up a little bit by pushing someone else down. Or we can look at them and admit that they are going through things that all of us have gone through. They just happen to be going through them very publicly. And we can sort of start to build an empathetic connection with them.

I think there is a reason after she had a breakdown [that] so many people changed their tune on Britney Spears. People feel very protective toward her now, and they really did not when she was just the “Baby One More Time” girl. Even when she was mid-breakdown, people definitely were enjoying the spectacle of this broken woman who had it all and fell apart in public. But even as that was happening, more and more people were beginning to identify with Britney Spears, the woman with problems, in a way that they never did with Britney Spears, the perfect teenager who was both sexy and never had sex ever.

Shares