The last Friday night I spent in my childhood home, five bombs exploded throughout the city of Cali. Like too many other Colombians, my parents had recently given up on the country and, after much hesitation, had decided to seek an uncertain future in the U.S. I had invited my high school friends over for a last hurrah, and after an evening of eating pizza by the pool, we were indoors getting ready to go clubbing.

Suddenly, the house was rocked by a tidal wave of vibration that rattled every window, an overpowering force so deep and dull that one couldn’t really call it a noise. “A bomb,” somebody stated, a little too matter-of-factly. We turned on the radio news. The blast we had heard was a car bomb that had gone off in front of a Drogas La Rebaja, a convenience store at the entrance to the neighborhood. The other bombs, we were dismayed to learn, had exploded on the other side of town — precisely where we were headed. Growing up in the era of cartel violence can really warp your priorities. Darn, we thought, there go our plans.

I bring up this story to make clear, from the start, the baggage I bring to the viewing of “Narcos.” When episode 7 of the new season opens with an attack against a Drogas La Rebaja, I know exactly what that sounds like. I am not, by any stretch of the imagination, an unbiased reviewer, but that is precisely why people interested in the show should read this article. I wrote about the show's first season last year, and while my appraisal was not wholly uncritical, I was rather impressed with the show.

Many Colombians had complained about fake accents, unhistorical details, or even the mere idea of returning to the drug wars when a peaceful and prosperous Colombia is finally emerging. By contrast, I found the show surprisingly authentic and saw it as a cathartic opportunity to share with the world my beloved country’s tragedy. But while the new season preserves many of the show’s aesthetic virtues and even gains authenticity by casting more Colombian actors in key roles, in the end it takes “Narcos” in a depressing and disappointing direction.

***

This summer, one of my students gave me a nasty shock at the beginning of class. I teach at a private high school full of diligent, well-meaning teenagers. Yet that morning, as I settled in among the students, I turned left and saw a pair of mocking eyes staring in my direction, framed by a side part and mustache I knew only too well. The face was printed on a T-shirt, and it couldn’t have contrasted more strongly with the kind, innocent look of the girl who was wearing it.

“You shouldn’t be wearing that,” I found myself saying, while my head seemed to be shaking nervously all by itself.

My words took her off guard; she looked confused.

“Your shirt. You shouldn’t be wearing that,” I repeated. “Don’t wear that. That was a very bad man. A very bad man.”

The poor girl stared, mortified, at her T-shirt and said something to the effect that it was her brother’s. Her words allowed me to gain better control of myself, and I explained in a few sentences what Pablo Escobar had done to my country.

“To a Colombian, that’s like wearing a Hitler shirt,” I concluded, and from the look on her face, I could tell she finally understood my reaction. She was merely wearing a design that, for reasons unknown to her, was trending in the popular culture. As her profuse apologies after class made clear, there had been no malice in her choice of clothing.

That’s what disturbed me most about the incident.

Then again, I should have seen it coming. That my student was wearing a shirt stamped with the picture of one of the most ruthless murderers in recent history is unsurprising if one considers the social-media marketing that Netflix has employed to promote the show.

Pablo's #WisdomWednesday pic.twitter.com/UXsdWg455s

— Narcos (@NarcosNetflix) October 14, 2015

Just a little black humor? Perhaps. But tell that to the families of the hundreds of Medellín police officers that he killed or the orphans of the Avianca flight that he blew out of the sky. My student didn't know any better, but the show's promoters have no excuse. To turn those tragedies into marketing is sick.

***

Fans of “Narcos” may object that the show isn’t its marketing. The sad truth though is that the second season falls in line with the marketers’ approach, changing the nature of the storytelling and turning it in a deeply troubling direction. Then again, many critics have praised this turn. The Telegraph has called the new “Narcos” “a slick, stylish delight,” while a Vox reviewer who had panned the first season has now said there is “so much to love.”

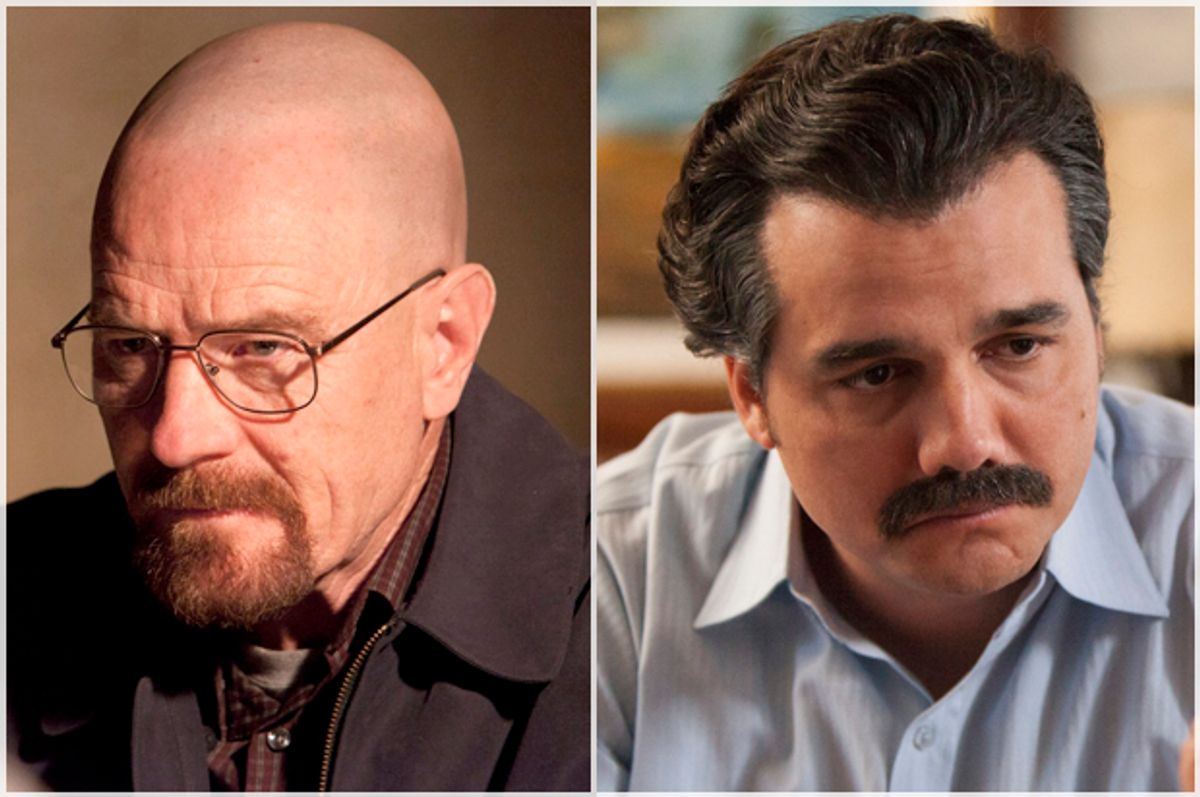

Unfortunately, for “Narcos” to become a “delight” is precisely the problem. To tell the story of Pablo Escobar as entertainment — to approach it merely as an alternative to fictional gangster series like "Breaking Bad" or "The Sopranos" — is to rob his countless victims of their reality, to murder them all over again.

When “Breaking Bad” debuted, audiences were captivated by the premise behind Walter White’s character: a brilliant and mild-mannered chemistry teacher driven by dramatic circumstances to become a ruthless meth dealer. The show is an excellent study of the addictive quality of evil, how it forces its users to take ever larger doses — or the way it can metastasize through the soul like the literal cancer spreading through Walter White’s body, claiming ever more of him. In exploring this process, the show brilliantly keeps White’s character sympathetic, human, allowing viewers to become immersed in his experience — not only pitying him but even rooting for him as he destroys his life and those of people around him.

The second season of “Narcos” appears to have taken a page from “Breaking Bad.” As the series follows Escobar during his final fall, the writers’ primary aim seems to have been to develop him into a compelling character that can keep viewers glued to their screens. And they largely succeeded. Coupled with Wagner Moura’s tremendous talent, this approach yields considerable narrative payoffs, turning Escobar into an attractive, memorable anti-hero. Yet for all these gains, Escobar is not Walter White, and by casting him in that light the show lies.

To be clear, the problem is not that the second season strays much deeper into fictional territory — though it does. Even a show based on history has to be watchable, and creative license is justified if it allows a story to communicate its most significant truths. Yet when dealing with historical events, especially ones as tragic and recent as the ones in question, storytellers must adhere to standards that reach beyond aesthetics. A movie about 9/11, for example, bears a tremendous responsibility to the victims of the attacks and their families, and filmmakers would sin in ignoring that duty in pursuit of commercial or even critical acclaim. Sadly, “Narcos” does exactly that when it delves into Escobar’s interior life.

Granted, the divide between Escobar’s two natures as loving family man and psychopathic monster are full of dramatic potential (even if the trope is used in every gangster movie ever made). Moreover, it is perfectly legitimate — even necessary — for stories to humanize the monsters of history. There is a great risk in pretending that Osama bin Laden or Adolf Hitler were not real human beings. Yet the new season tips the scales too far in the direction of relatability, adopting the kingpin’s point of view far too often, taking almost at face value his claim to be a man of the people.

We’re treated to scenes of poor Pablo, as his empire comes crashing down around him, gazing longingly at his daughter’s abandoned shoe, poor Pablo holding a bunny, poor Pablo dealing with daddy issues, wishing he could become a farmer living a simple life. Like Walter White, he begins to seem like a man driven by the love of his family and desperate circumstances to do some very bad things. Except, of course, that White’s actions were never about providing for his family but about making up for his sense of weakness and failure.

To be fair, “Narcos” does remind us on occasion that its main character is a monster, as when we see the horrific results of a bombing campaign from the point of view of an everyday Colombian family, or when a brief and sad sketch pays tribute to the rank-and-file police officers who dared take up the job. Still, it’s telling that those scenes, which should evoke in viewers a sense of pity and fear, actually filled me with a sense of relief — relief that, at last, the perspective of those of us who lived in terror of Escobar and his ilk had a place at the table. The series gets too close to whitewashing Escobar’s image, developing his character in a way that does little to reveal the truth, and much to obscure it. To approach Colombia’s war with the cartels in this way is not unlike telling the story of 9/11 from Osama bin Laden’s point of view.

In aiming primarily at entertainment, the priorities of “Narcos” have become exploitative. Escobar’s victims weren’t characters; they were real people who even now have families that still mourn them. “Narcos” ought to be a record of a real — and massive — human tragedy, not a “slick, stylish delight.” It can never be just a show.

Don’t watch it.

Shares