Are there some things we’re better off not knowing? In the age of calls for political transparency, of the dominance of TMZ and endless celebrity news, of the constant tweeting by celebrities on their most pedestrian thoughts, it’s hard to make a case that anything can or should be kept secret. When we can find just about anything on the internet with just a few keystrokes, it’s hard to argue that we either can or should let mysteries just sit around. As a longtime journalist, I’m steeped in the idea that revealing and reporting the truth is almost always the right way to go, and that readers can figure out how to handle the news.

But the latest revelation — the outing of the likely identity of the enigmatic Italian novelist Elena Ferrante — has a lot of people, me included, a little queasy.

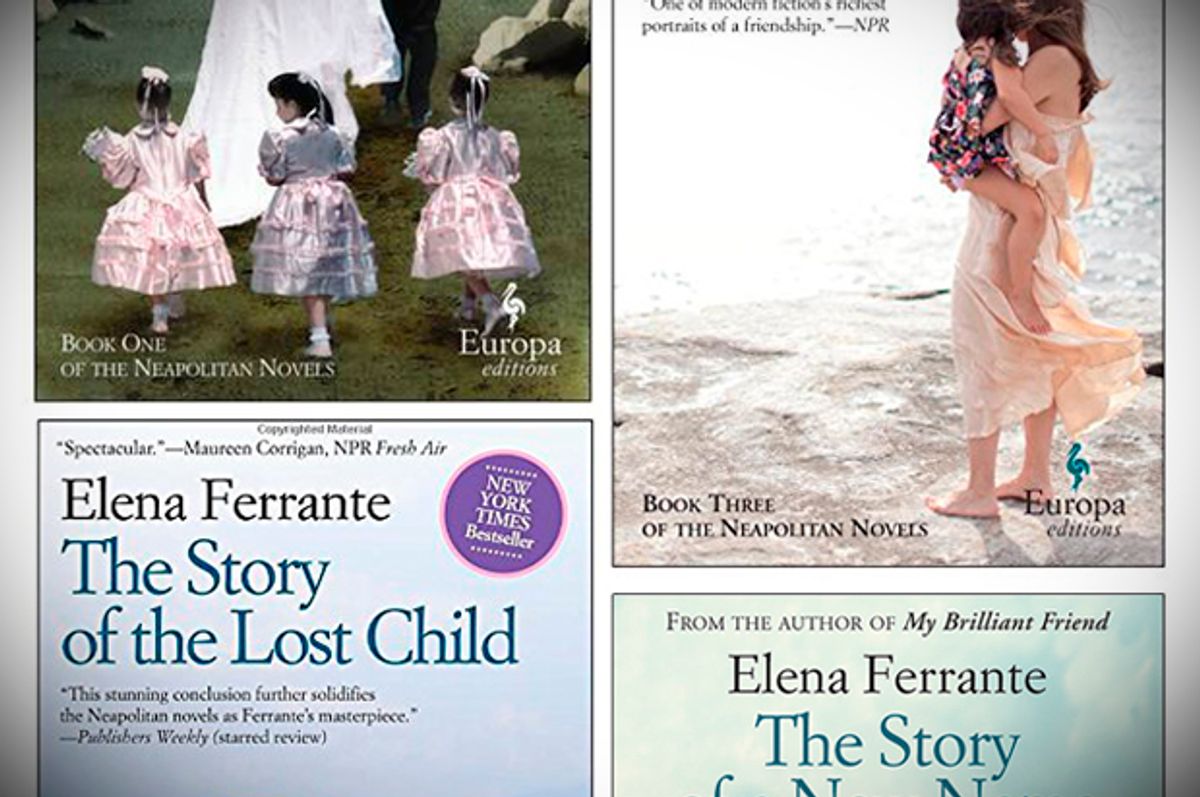

Ferrante, of course, is the nom de plume of a writer whose four novels about postwar Naples that have become among the biggest sensation for a translated novelist in recent memory. Despite much speculation, Ferrante has not revealed her identity but on Sunday — spoiler alert! — the Italian business journalist Claudio Gatti has used financial records to reveal that the author is very likely to be a Anita Raja, a Rome-based translator who works for Ferrante’s European publisher. The New York Review of Books published his story early Sunday morning.

“The biggest mystery outside Italy about Italy is who is Elena Ferrante,” Gatti told the New York Times. “I’m supposed to provide answers, that’s what I do for a living.”

“The process has taken him months,” The New Yorker’s Alexandra Schwartz wrote. “If only someone had gotten him interested in Trump’s tax returns during the primaries, just think where we might be today.”

This joke about Trump, tossed-off though it may be, strikes me as an important line. To report aggressively on the finances, or anything else, of a politician or public figure or anyone controlling huge sums of money, seems like the right thing to do in almost all cases.

But a novelist, who writes about imaginary things? Many of us have been curious about who Ferrante “really was,” but what aspect of the public interest does it really serve to know these things about her and her financial details?

It was partly because of the way publicity was getting tangled up with the author’s role that J.D. Salinger went into seclusion after the success of “The Catcher in the Rye” and Thomas Pynchon disappeared after a photographer came to take his picture. (In the ‘70s, Pynchon sent a comedian to accept his National Book Award for him.)

Some — including Gatti — have claimed that seclusion can be a coy kind of publicity stunt. It certainly enhances an author’s mystique in some ways.

But Ferrante — whoever she is — may’ve just wanted to be able to create a fictional world (one grounded, in her case, in real history) without having her own life intruding on it. Ferrante has said that it was essential to her work as a writer. Given the way women's identities have typically been controlled by men, there is an important feminist context to this as well.

I’ve only read a little of Ferrante’s first Neopolitan novel, “My Brilliant Friend,” but this still makes me uneasy. In the age of the Internet — and widespread government surveillance, and corporate data collection — it was probably inevitable that the author’s identity would come out at some point. But it also makes Ferrante’s ability to hide in plain sight a wonderful kind of pre-modern survival.

Call it childish, but the idea of disappearing into a world an author has sketched, without the intrusion of anything else, is a crucial foundational experience for a lot of book writers.

These days, there all all kinds of anonymous writers and artists, from the children’s novelist Hieronymous Bosch to the musicians The Residents to the British artist Banksy. Why not allow culture to retain some of its mystery?

Shares