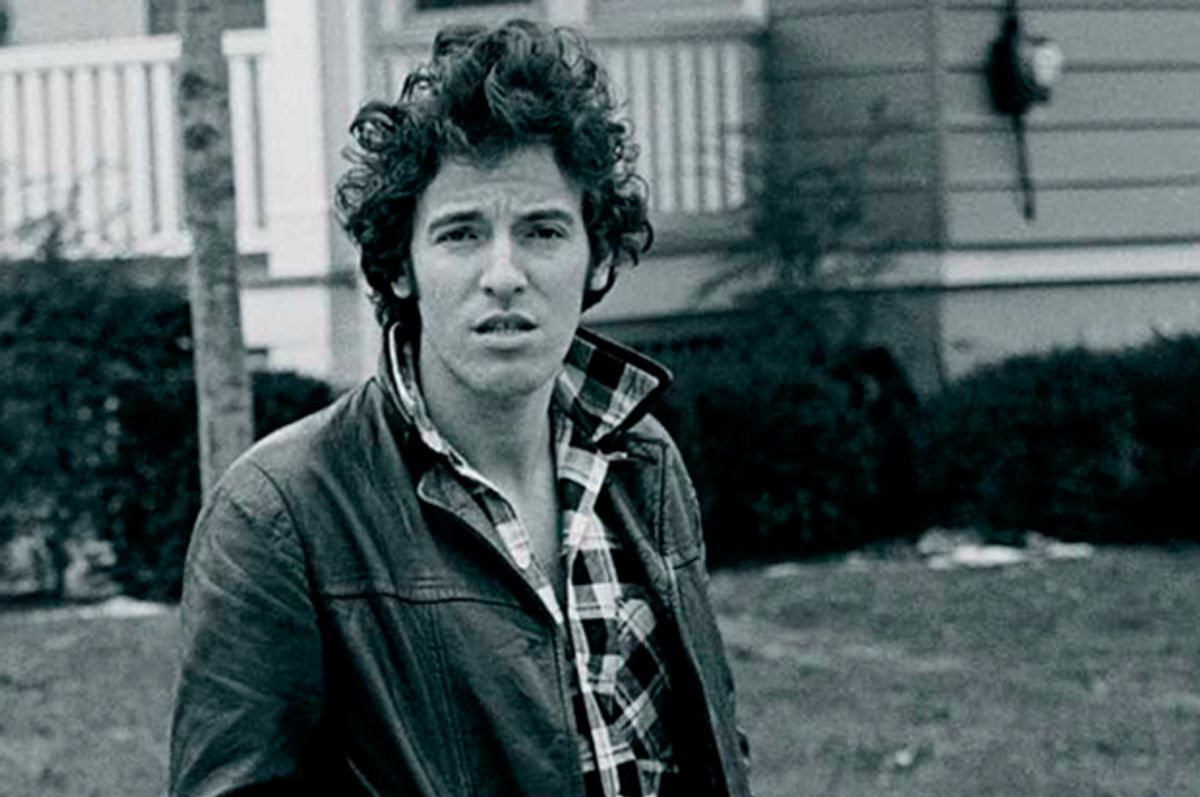

Bruce Springsteen’s legendary concerts aren’t for the faint of heart, the cynical, or the disbelievers. If the man asks you to put your arms in the air, well, you better put your arms in the air. If he asks you to give him a train, well, you give that man a train. Similarly, Springsteen’s recently released autobiography, “Born To Run,” will ask a lot of the reader, and to get the most out of it, you have to be willing to throw your emotional lot in with him for the full duration of the book’s 500+ pages. It is undeniably thrilling, breathtaking, heartbreaking, blunt and aspirational. There are passages that echo the likes of Steinbeck and even Faulkner in the beauty of his prose, sections where you’ll need to put the book down for a few minutes and soak it all in and yet others that read like your dad sending you an email, typing in ALL CAPS.

Every summer, a group of Springsteen tourists from Europe arrive in New Jersey to get bussed around Springsteen’s former stomping grounds: from the Asbury Park boardwalk, to the corner of 10th Avenue and E Street in Belmar, to Main Street in Freehold. It would be easy to mock them, except that (almost) everything is still there, and it is absolutely a profound experience. All of Springsteen’s childhood homes in Freehold are within walking distance from each other, and all are within earshot of the bells at the St. Rose of Lima church. And that’s where “Born To Run” begins: in Freehold, on Randolph Street, on Institute Street, and on South Street.

If you spend any time researching the early days of Bruce Springsteen’s career, it quickly becomes apparent how much of the here and now of Springsteen echoes directly back to his time in Freehold. “Born To Run” absolutely solidifies that belief because Springsteen brings himself and the reader back there again and again and again. His musical influences, his ability to play in front of any audience at any venue, his skill as a bandleader, the combo of rock and soul that he fused together and made uniquely his, his dogged determination to make it because he didn’t fit in and had nothing else that gave him hope. Others have tried to write about his childhood before, and although some (like Peter Ames Carlin, who authored “Bruce” in 2012) had Springsteen’s tacit permission to dig into his past and for people to open up, it was never going to have the power and immediacy that the stories are going to have from the person who told it.

It is astounding how unvarnished and open he is about his relationship with his parents, and specifically, his troubled relationship with his father; sure, he’s probably holding something back, but it’s hard to imagine what else could be left, as he intertwines it with tales of his own depression and emotional crises, and his battles against the family illness he inherited. It is an accounting, it is an atonement, it is a reckoning. It is uncomfortable but it is also extremely necessary. It is necessary because it is the thing that explains why Bruce Springsteen, as we know him, exists. It is also exceedingly brave, no matter how famous he might be.

Unsurprisingly, Bruce Springsteen happens to be a great storyteller. No details are accidental, and if he makes a point, he always connects it later on. He relates a story about the class divide between the working class kids who lived inland and the wealthier kids who lived on the beach, and how he got spit on by the latter when he came to the beach to play with one of his early bands. To get to the beach you had to drive through the tony enclave of Rumson, where Springsteen ended up living once he’d made it. “I could still feel the shadow of that spit that hit me long ago when I moved to Rumson in 1983, 16 years later. At 33 years old, I still had to take a big gulp of air before walking through the door of my new home,” he says.

But the sections of the book that are the most compelling are where he opens the door onto his creative, songwriting and recording process. While these are subjects Springsteen has discussed (or written about before) the telling here feels more direct. The 20 or so pages around the writing of the “Born To Run” album are some of the strongest and most compelling material in the book; that’s likely no accident, because that was the moment when everything changed: “’Born To Run’ was the dividing line.” He recalls his motivation and thought process with stunning clarity, and you feel like you are back there with him in that moment. It is the closest you will ever come to witnessing genius; if the book stopped there, it would have been a tremendous gift for that alone.

If you are a huge fan of this man and his work, “Born To Run” contains all the stories you have ever heard or known, collected in one place, and after a while it begins to feel almost Biblical. Here are the legends, here are the secrets, here are the eulogies, here are the jokes, here are the tragedies. And it is good to hear them told in Springsteen’s own words, in his voice, through his lens. (There's even a companion album available, "Chapter & Verse.")

Playing at the Upstage club for the first time: “I saw two guys pull chairs onto the middle of the dance floor and sit themselves down in them, arms folded across their chest, as if to say, ‘Bring it on,’ and I brought it. (The two guys would turn out to be future E Street bassist Garry Tallent and once and future bluesman Southside Johnny Lyon.)

On meeting Clarence for the first time: “It was a dark and stormy night.”

Springsteen addresses making the decision that he wanted to be on the cover of both Time and Newsweek in 1975: “THIS WAS NO TIME TO BUCKLE! I was reticent and would remain so, but I needed to find out what I had.”

About getting kicked out of Disneyland: “SCREW YOU, FASCIST MOUSE!”

About the '80s: “The Born In The USA tour was notable for the sartorial horror sweeping E Street nation. The band has never looked and dressed so bad.”

There are countless other similar moments throughout the book; fans looking for their favorite tales will not be disappointed.

Fans looking for dirt may, however, may be dissatisfied. On the subject of the lawsuit between Springsteen and his first manager, Mike Appel, he effectively distills the anger and hurt he’s previously expressed into this one critical line: “Mike’s mistake was that he fundamentally misunderstood me.” His failed marriage with Julianne Phillips: “I dealt with Julie’s and my separation abysmally . . . . I deeply cared for Julianne and her family and my poor handling of this is something I regret to this day.” In terms of actual dirt, well, that’s there too: There were a lot of women. (A lot.) He may boast, but Springsteen is at least discreet, and recounts what he does recount affectionately and good-naturedly.

Every member of the E Street Band gets his or her moment in the spotlight within “Born To Run” (as well as long-time manager Jon Landau). Springsteen also breaks down, several times, what it is about the band that makes them different, that allows them to survive and endure throughout the decades. “We are more than an idea, an aesthetic. We are a philosophy, a collective, with a professional code of honor,” he says about the E Street Band. “We don’t hide our cards. We don’t play it cool. We lay ourselves out in full view . . . We aspire to be understood and accessible, a little of your local bar band blown up to big time scale.”

On the subject of E Street, there is much in this book about the late Clarence Clemons; he was Springsteen’s friend and onstage foil, and he was the Big Man, after all. But amidst the mythology Springsteen also talks about what it was like for Clemons to be the only African-American in the E Street Band, and what that meant. “...we lived in the real world, where we’d experienced that nothing, not all the love in God’s heaven, obliterates race. It was a given part of our relationship.” Springsteen recalls an incident where someone who Clarence knew threw a racial epithet at him. “‘I know those guys,’ he said. ‘I play football with them every Sunday. Why would they say that?’ I should’ve answered, ‘Because they’re subhuman assholes’ but I was caught blank, embarrassed by the moment myself, and all I offered up to my friend was a shrug and a mumbled, ‘I dunno.’”

If you aren’t necessarily a die-hard Springsteen fan, but are a fan of rock and roll and its history, you will also see yourself in these pages. That’s because Springsteen’s own fandom runs amazingly deep; he gets what it means to be a fan because he was (and in some cases, still is), the kind of fan who makes geographically-specific mix tapes for a cross-country road trip. “We played to crowd after crowd who let us know they felt about music the way we felt about it, with the same all-consuming, anticipatory rush you knew at 16 unwrapping your favorite group’s latest LP…,” is how Springsteen describes the response of the audiences in Europe the first time he went over with the E Street Band for a proper tour in 1980.

And in the chapter about the 1999 Reunion tour, Springsteen describes how he felt rehearsals hadn’t been going well and was considering calling the whole thing off, until he made the decision to open the doors to the fans who had been skulking underneath Convention Hall during rehearsals. “I’d looked into those faces and found what I was missing. As we’d slogged away for weeks on the Convention Hall stage in isolation, trying to pump life into our much-vaunted songbook, there’d been only one thing missing: you.” There will likely be more than a few tears staining page 433 of “Born To Run.”

Springsteen writes so intently and passionately about music in a way that we don't usually get to witness: His words here about the likes of Elvis, Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Sam & Dave, Frank Sinatra and later, even as late as age 63, the Rolling Stones, are full of love and affection. Springsteen’s retelling of rehearsing with the Stones prior to appearing with them in Newark, New Jersey in 2012, is as breathless as any teenager’s: “These are the guys who INVENTED my job! They have been stamped on my heart since the chunking chords of ‘Not Fade Away’ came ripping off the little 45 I bought at Britt’s Department Store…” This is not something that ever comes out the same way in interviews. It is a beautiful thing to have here.

The ending of the book is another moment that will put a lump in your throat if you love Springsteen’s music or at least appreciate his place in rock and roll. But just a few pages earlier, Bruce goes off on a rant that is just as important and just as heartfelt. He describes the moment when an unprepared Jake Clemons showed up to work with Springsteen to possibly join the E Street Band in the wake of his uncle’s death. “People always asked me how the band played like it did night after night, almost murderously consistent, NEVER stagnant and always full balls to the wall. There are two answers. One is they loved and respected their jobs, their leader and the audience. The other is… because I MADE them. Do not underestimate the second answer.”

One can imagine many motivations for this work, and it’s hardly a spoiler to note that many times in the book, Springsteen matter-of-factly notes that he and the E Street Band are probably the last of their kind. By the end, you feel as though Springsteen has let you stand witness to the entire arc of his career, whether you were there back in the day or just climbed on board the train a couple of albums ago. “Born To Run” is a great entry into the pantheon of rock and roll autobiographies. The book preserves Springsteen’s legacy, and manages to enhance it further. But it definitely lets everyone know that there’s only one Bruce Springsteen, and when he leaves this planet (hopefully many years from now), we’ll never see the likes of him again.

Shares