Colin Dickey’s new book “Ghostland” tells what seems like the whole story of the nation through a recounting of haunted houses. Roaming from the Mustang Ranch near Reno, Nevada — a legal brothel in an area dense with tales of prostitutes’ ghosts — to Civil War sites in Shiloh, Tennessee, near the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, the book finds that ghost stories typically reflect the region in which they’re told. Its subtitle is well justified: “An American History in Haunted Places.”

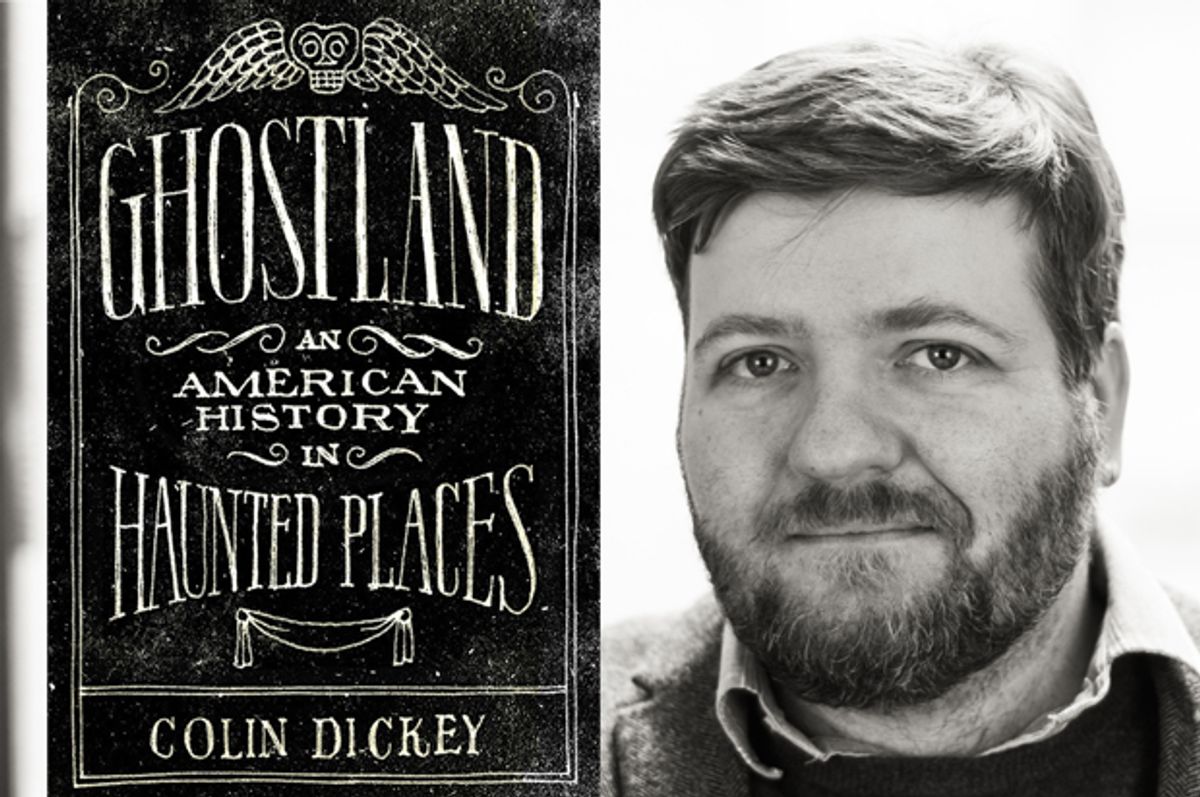

Dickey earned a doctorate in comparative literature at the University of Southern California and now lives in Brooklyn; he teaches creative writing at National University. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Your subtitle includes the phrase “An American History.” Is there something about this country — which is younger than most other Western societies — that gives it a special fascination with ghost stories and haunted houses? Or does it resonate here in a particular way?

In one sense, no; it’s pretty universal. You find ghost stories and haunted houses the world over. But what is different about America’s history is that it is young, so the ghost stories we’ve accumulated tend to have a different quality and variety than what you find in Europe and Asia. And the specific nature of our own history — especially some of the more fraught and unresolved aspects of it — tends to get expressed in ghost stories quite often. And that’s the thing I wanted to focus on.

Let’s pick one specific place and talk about how you handle it in the book. The natural place to start with seems to be the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose. Partly because you grew up not far from it and because, I think, Shirley Jackson, author of “The Haunting of Hill House,” grew up nearby as well. Tell us a little about the place and how you try to bring it to life in the book.

As you say, I grew up nearby; it’s often listed as perhaps the most famous haunted house in the world.

The story, briefly, is that Sarah Winchester, who built it, was the daughter-in-law of Oliver Winchester, who bought the Winchester Rifle Company. And she became, according to legend, convinced that her family was being haunted and pursued by the ghosts of everyone that had been killed by Winchester rifles and had built this sprawling, 160-room Victorian house as a means to keep these ghosts at bay.

I got interested in that story because there are so many aspects that drill into the central mythology of America. Whether it’s the fascination with firearms, the westward expansion of white Americans and the fallout of the genocide perpetrated on Native Americans, the idea that Sarah Winchester would be haunted by the victims of the gun that “won the West" . . . as well as our attitudes towards a woman living alone, who after her husband and daughter died chose not to remarry, chose to continue to live in this sprawling Victorian mansion. Sort of like Miss Havisham out of “Great Expectations.”

Once I started the research the story, I saw that much of the legend is not entirely true. It showed me how a fictitious story takes root and becomes so ingrained in American culture.

Your book ranges across the whole country. I wonder if you saw any tendencies between different regions of the country and their haunted properties.

It was fascinating for me, as someone who’s spent most of his life on the coasts, to explore different ways haunting manifests itself. In the South, for instance, there are a lot of cities that trade on their haunted reputations: Richmond, Virginia; Savannah, Georgia; New Orleans, Louisiana.

They advertise themselves to tourists. But they’re also very cautious about curating how those stories are told. So one of the first things that struck me was how the ghost stories that get told on tours and in guidebooks are [about] white ghosts. There were very few stories about Richmond’s involvement in slavery and how that might have expressed itself in the folklore.

So different parts of the country seem to use ghost stories and legends to reflect certain things back to themselves and others.

So in Richmond, [there is] a lot less consciousness about slavery — even though this was the capital of the Confederacy.

Right, whereas in New Orleans, there’s more of a history of taking aspects of black culture and marketing it to tourists — whether it’s jazz or voodoo. So in New Orleans you’re more likely to hear stories about black ghosts; New Orleans has built this reputation of packaging black culture, mostly for black tourists.

This is a very analytical and thoughtful book but also a work of obsession. How did you get drawn so deeply into the subject of haunted places.

Partly, as I mentioned, [it] stems from growing up near the Winchester House. But it also came from when my wife and I bought our first house, going through so many homes, many of which had been foreclosed — this was 2008, near the beginning of the housing crisis. And I felt for the first time the weight of the lives that had been lived in these places, even if I had been in the house for only an hour — all of the different ways a previous occupant could leave their mark on a home.

And that got me thinking about how we use the language of ghosts and hauntings to talk about a whole range of aspects of personal and cultural histories. And I dove into that.

Shares