They're an unlikely pair, Tom Brokaw and Ben Stiller. Yet in the past week, both men have emerged as a dynamic duo in the realm of cancer, bringing real talk to an often exasperatingly badly communicated subject.

We're used to a particular script when it comes to the public conversation around cancer. We're used to hearing wishful talk about "the" cure for "this" disease, even though anyone with a minimum of personal experience knows that cancer is a variety of often quite distinct conditions. There are several forms of breast cancer alone. You and I may both have had cancer, but my late-stage melanoma was not your Hodgkin's lymphoma. The treatments for cancer are varied and there will never be a single agent. And with more and more of us aiming for simply living with a stabilized disease, the notion of "cure" simply isn't the only goal in Cancer Town anyway.

Yet magazine covers and morning news shows still constantly peddle the chipper narrative of some celebrity who "beat" cancer — often with an inspiring combination of God, a positive outlook and, oh yeah, the top doctors and best treatments in the world. And if things take a turn in a different direction, the story then swiftly changes to the tragedy of the person who "lost a battle." Because sure, getting sick is something you can totally win or lose at.

Just a few months ago, I watched a former television actress being interviewed about how she and her husband "beat" cancer by changing their diets and not accepting defeat and I swear I thought I was going to lose my battle with keeping my breakfast down.

So what a pleasant change of pace, within this always painful subject matter, to witness two high-profile men writing accurately about their own cancer experiences.

First, in a Sunday New York Times essay, veteran journalist Tom Brokaw wrote eloquently about how he's been living with his multiple myeloma over the past three years. The 76-year-old news veteran relayed the good news that the "cancer is in remission, and I take the word of my medical team that I am doing well and should beat the standard life expectancy." But he added, "Even in remission, cancer alters a patient’s perception of what’s normal."

This is no victory lap. This is a story of 24 pills a day and bone damage and pain and fatigue. It's a story of the surreal experience of watching other people go through cancer at the same time and not survive it, of coming face to face with mortality, of recalibrating priorities, of gratitude for scientific achievement and of understanding that like all of us, "I’ve had a lot more experience living than dying."

Brokaw is not sentimental. His words are instead reminiscent of those of Roger Ebert, who lived with the experience of cancer for 13 years before his death in 2013, and who wrote in 2011 that "I have plans" but "I have no desire to live forever." His is a thoughtful meditation on the reality of life with cancer, the emotional and physical cost of the privilege of being able to be called a "survivor."

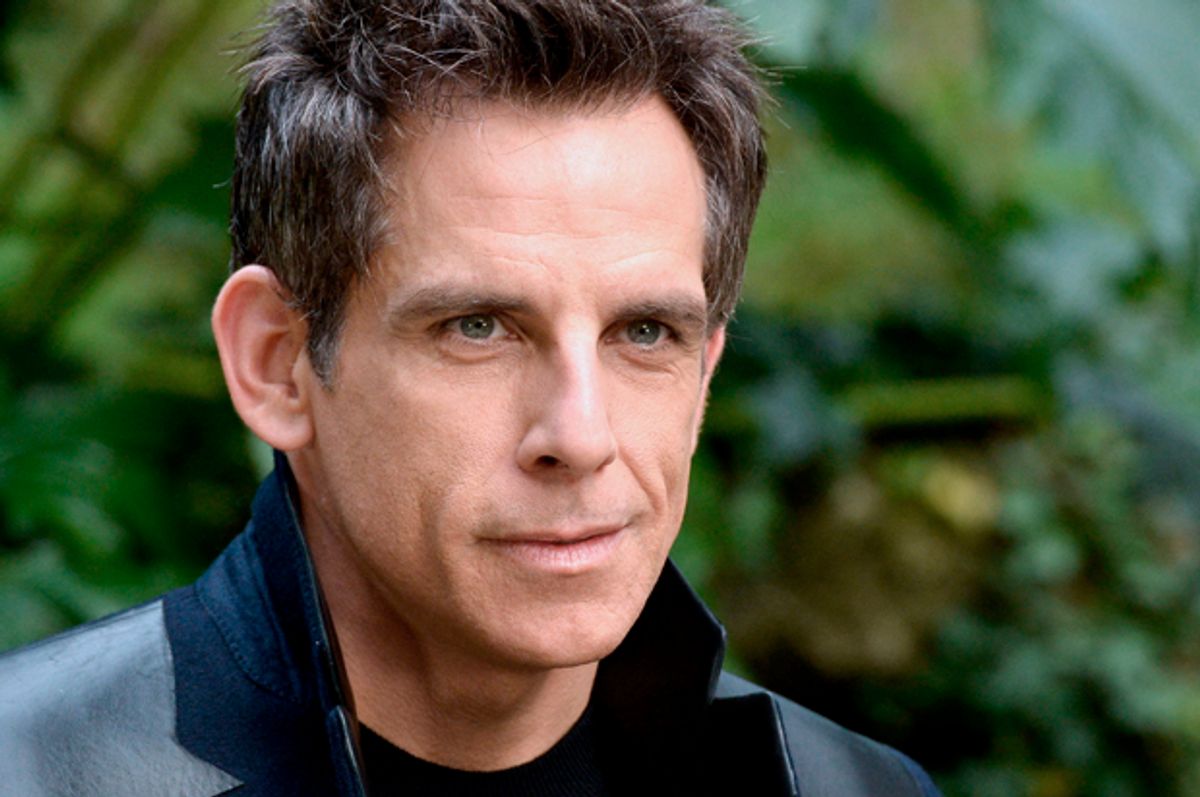

And then there's Ben Stiller, who set the tone for his Tuesday Medium post for the Cancer Moonshot with a famous image of the excruciating zipper incident from "There's Something About Mary." He then opened with a killer first line: "So, yeah, it's cancer."

The actor revealed that two years ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, underwent surgery, and three "crazy roller coaster ride" months later was declared cancer free. He wrote to raise awareness, with great nuance and empathy, about the prostate-specific antigen test that he believes saved his life — a test that he started getting four years before the American Cancer Society recommended age of 50. He had no symptoms. He was not a member of high-risk population.

But Stiller had a medical team that recommended testing, noticed his changing results and, as he put it, was willing to give him "a slightly invasive physical check" and a biopsy. Had he waited longer to start watching for his cancer, his results would no doubt have been very different.

Stiller wrote of his experience with the understanding that he is one guy, who had one type of treatment — in large part because he was able to have a collaborative, constructive relationship with his doctors. He knows — unlike the "Just juice and think happy thoughts!" brigade — that what worked for him isn't going to be a fit for everybody. He explained why the current recommendations exist and the up- and downsides of following them. He was not offering medical advice.

He was instead doing something else powerful, saying, "Men over the age of 40 should have the opportunity to discuss the test with their doctor and learn about it, so they can have the chance to be screened. After that an informed patient can make responsible choices as to how to proceed." Knowledge. Curiosity. That's good stuff.

In their essays, neither Brokaw nor Stiller spoke in "battle" metaphors. They did not declare themselves victors, nor did they offer pat, easily digestible tips on how be a "warrior" in an often unbearably crappy situation. They instead spoke with humility and heart and honesty. And when the cancer conversation is still so often mired in ignorance and fear, that's some pretty great medicine.

Shares