Multinational corporations have long lusted after India's market of 1.3 billion people, but the world's biggest democracy has proven to be a tough nut to crack. In October 2012, India’s first Starbucks outlet opened after five years of fits and starts that humbled CEO Howard Schultz so much he tacitly acknowledged his company’s expansion plans in India wouldn’t be as ambitious as previously stated.

While the prospects for foreign companies have improved somewhat since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office, India remains one of the most difficult places in the world for companies to operate. The World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business measure places India 130th of 189 countries in its 2016 ranking, one notch below the West Bank and Gaza and well below Mainland China, which placed 84th. (The U.S. is seventh and Singapore tops the list, if you were wondering.)

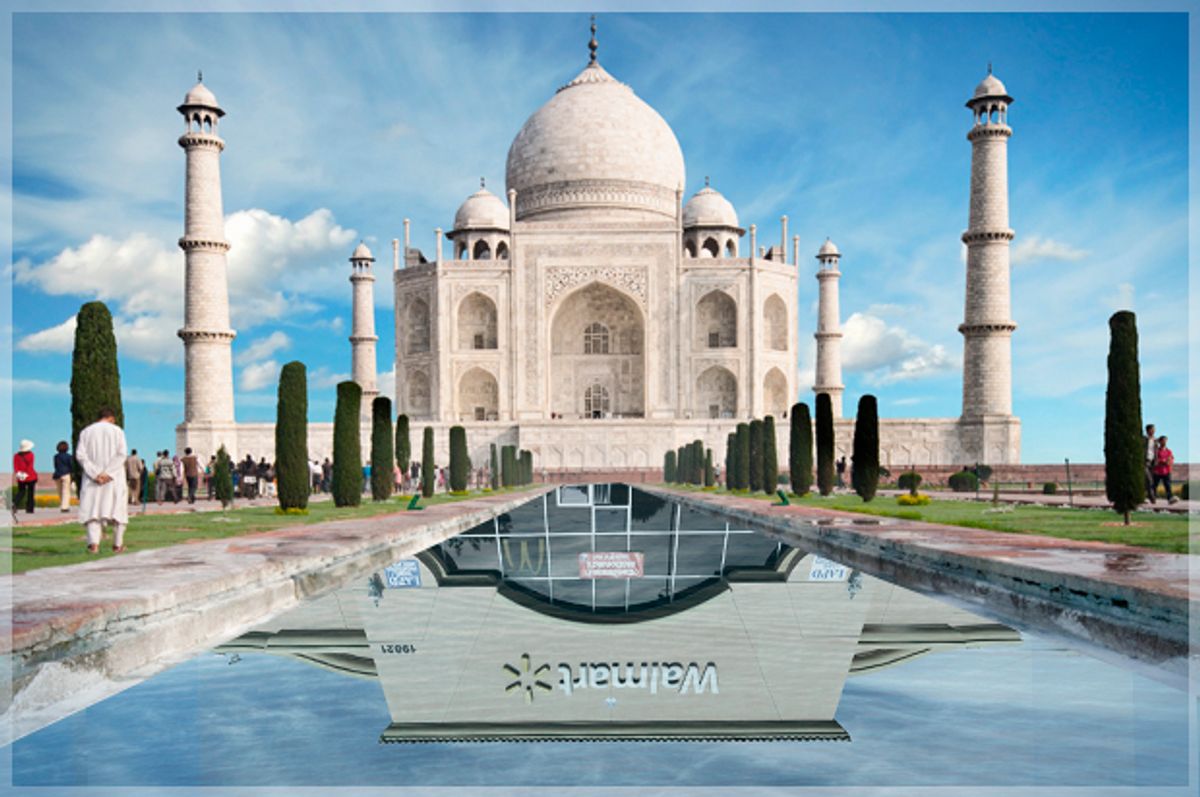

Yet India is too big for multinational retailers to ignore, and Wal-Mart Stores has been trying for years to figure out how to navigate the country’s rules to grab a bigger share of the country’s $600 billion and growing Indian retail market. The U.S. retail giant’s experience in trying to get its share into the Indian market in some ways reflects challenges it’s faced elsewhere — it's faced expensive lawsuits in Brazil where workers have stronger workforce protections and given up on Germany completely because of the country’s rules barring larger companies from using their size to price out smaller competitors — one of Wal-Mart’s keystone strategies. Unlike with Germany, however, Wal-Mart is not willing to give up on a massive yet underdeveloped retail market with a fast-growing middle class.

In 2007, the Bentonville, Arkansas-based company first entered Indian market via a joint venture with Bharti Enterprises, a Delhi-based global conglomerate. Together the companies opened 20 cash-and-carry wholesale stores under the name Best Price Modern Wholesale. But the troubled partnership was plagued by bribery allegations in India that have since become part of a broader ongoing U.S. federal probe in which Wal-Mart is accused of illegally paying local officials in India, as well as Mexico, Brazil, and China, to expedite its business operations. Wal-Mart cried "uncle" three years ago and agreed to pay Bharti $334 million to buy out its investments and settle debts.

Adding to Wal-Mart’s troubles in India has been an ongoing national debate about whether or not to allow large foreign multinational retailers to operate in the country. Today Wal-Mart mantains the smallest of footholds on the Subcontinent, operating just 21 wholesale outlets in the country, about a fourth of the number of stores it owns and operates in tiny Honduras.

But recently, news emerged that Wal-Mart is poised to a major new play for the Indian retail market. According to insiders who spoke to Bloomberg, Wal-Mart is in advanced talks to invest $1 billion in Bangalore-based Flipkart Online Services, an e-commerce operation selling everything from refrigerators to its own brand of tablet covers and keyboards.

The agreement would give Wal-Mart a minority stake in the nine-year-old company founded by former Amazon.com software engineers Sachin and Binny Bansal. The cofounders, who are not related, realized that while Amazon.com was the runaway leader in online retail, the burgeoning Indian market was still largely underserved. Now Flipcart is one of the most popular sites in India and the Bansals are billionaires. The deal with Wal-Mart would give Flipcart the capital to challenge giants Amazon.com and China’s Alibaba as they grow their online retail operations in India.

Meanwhile for Wal-Mart, the deal not only gives it a share of Flipcart’s profits but could give the retailer a solid foothold on the Subcontinent, and a chance to grow its online strategies in a market that isn't dominated by Amazon.com — at least not in the same way it dominates in the U.S.

This push for international expansion is vital for Wal-Mart. On Thursday, the company warned investors that its fiscal 2017 earnings would be flat and it would slow U.S. new-store expansion through 2018, news that led to a drop of more than 4 percent in its stock price. The company is playing catch up against Amazon.com by aggressively expanding its warehousing and shipping operations. Its $3.3 billion purchase of Jet.com and a recently announced pilot program to offer low-cost, Amazon Prime-like shipping for $49 a year gives Wal-Mart two new tools for luring American consumers to its web-based business. But it could be years before Wal-Mart can challenge Amazon.com in its core U.S. market. So Wal-Mart's strategy is to go where Amazon is as weak as it is, a massive market known as India.

Shares