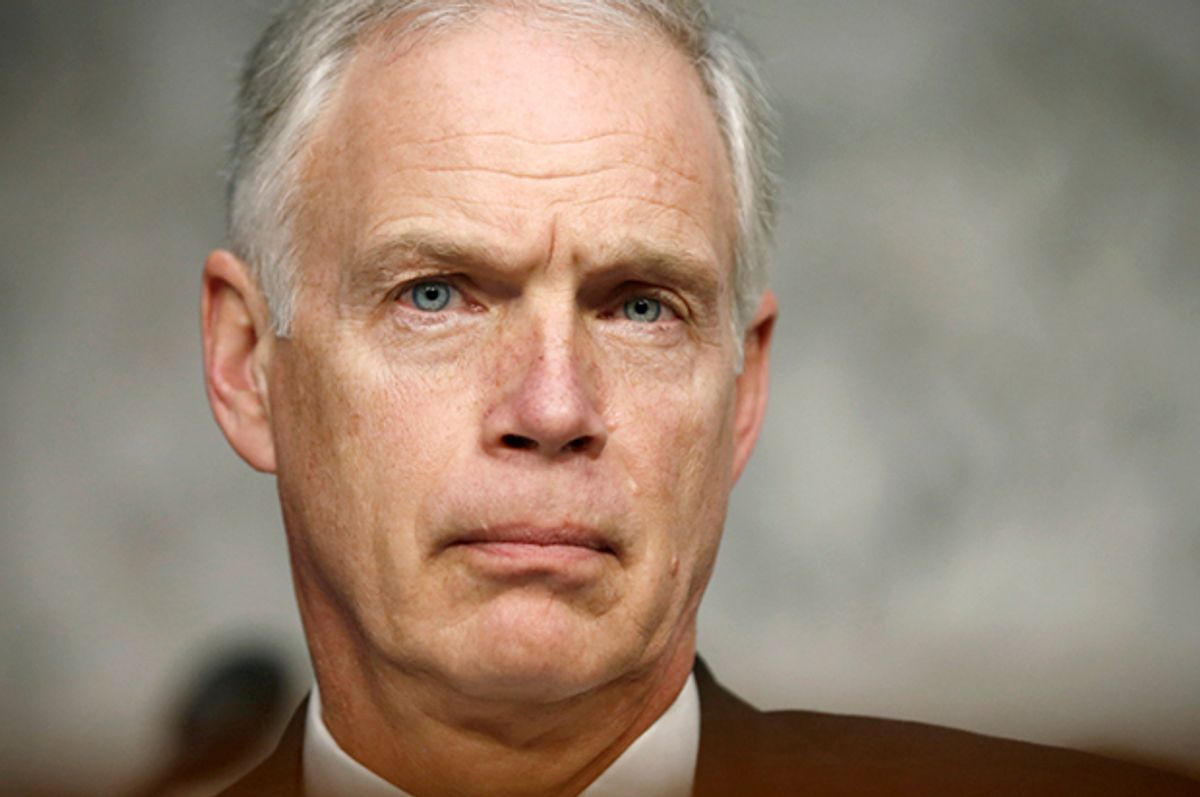

Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin is a right-wing Republican who, like many in his party, believes that the federally-funded social safety net is a disastrous failure and that private charity works much better at helping lift people out of poverty. But as Salon has discovered by looking through Johnson's family foundation's tax documents and his own financial disclosure statements, Johnson's own charitable foundation does not exactly represent the poverty-destroying generosity he claims will work so much better than government spending.

In 2013, for instance, the Johnson family's Grammie Jean Foundation gave $20,000 to the Oshkosh Opera House and only $1,500 to anti-poverty programs.

It's a strange choice from a man who has a long record of arguing that private charity works better to relieve poverty than taxpayer-funded programs like Medicaid and SNAP.

"After spending $19 trillion on a war on poverty, the total -- when adjusted for inflation -- number of Americans in poverty has increased from 29 to 47 million," Johnson said in a 2016 address released prior to the State of the Union. "Sadly, the war on poverty has primarily grown government, not prosperity."

To highlight his belief that private charity works better than government spending, Johnson has been touting the Joseph Project, a faith-based charity helping connect people seeking jobs to factory work.

"It is a joy, being able to participate in that, seeing people’s lives be turned around," Johnson told the Wall Street Journal in August. "That’s true conservative values and they work. You outsource compassion to the federal government, that doesn’t work so good. You show your compassion here in your community, one person at a time."

Johnson even blamed the violence and unrest that erupted in Milwaukee in August on federal anti-poverty programs and argued instead for "faith-based, community-based programs, helping individuals one person at a time."

Johnson is currently running a tough race for re-election against Russ Feingold, who held Johnson's Senate seat before Johnson ousted him in the 2010 Tea Party wave. Johnson's emphasis on charity over government programs has become an important part of his campaign to convince Wisconsin voters, especially in the wake of the Milwaukee unrest, that he is serious about alleviating some of the economic and social problems of the state.

Looking at Johnson's activities with the Grammie Jean Foundation, however, it doesn't appear that his belief in the power of charity really translates into action.

Family foundations are big in the news these days, as both presidential candidates have been accused of using foundations for corrupt ends. To be clear, only one set of accusations has much merit. The Clinton Foundation — which, unlike most family foundations, is a public, not private, foundation — is a highly-rated charity that spends 87 percent of its expenses on programs and services that give aid. Lengthy, expensive investigations into Hillary Clinton's time as secretary of state have turned up no evidence that she did special favors for Clinton Foundation donors, even though many in the press dearly wish it were otherwise.

The Trump Foundation, on the other hand, appears to have been used frequently as a slush fund for Donald Trump, who solicited donations for his private foundation and then pretended it was his own money in charitable giving, bought himself presents, used the funds to settle lawsuits and, in one case, donated money to the Florida attorney general, who then shut down a state investigation of Trump University.

Most family foundations sit somewhere between these two examples: They're not big, public charities that do a lot of good in the world like the Clinton Foundation, nor are they as clearly corrupt as the Trump Foundation. But it's worth taking a look at these middle-ground family foundations, because of what they show us about how the wealthy people who run them approach the concept of charity.

The Grammie Jean Foundation is a private family foundation that was set up by the Johnsons in 2009, and is headed by the senator himself. At first, it started off fairly small for such a wealthy family, but as this chart from its 2014 tax filings shows, that rapidly changed right around the time Johnson took office in 2011.

The amount of money in the foundation's accounts surged dramatically because, according to 2010 tax documents, Johnson and his wife donated a huge amount of money to the foundation, much of it in the form of Alcoa and General Electric stocks.

That stock gift happened right before Johnson took his seat in the Senate. He used to own an array of stocks, but as his financial disclosure forms show, he's gotten rid of most of them. Johnson even went to the press to brag about how much stock he unloaded in order to avoid the perception of a conflict of interest. Many of the stocks given to the Grammie Jean Foundation are from the same companies, and are presumably the same stocks that Johnson said he had unloaded. But the foundation, which was personally controlled by Johnson, didn't liquidate those stocks immediately. They remained in the its portfolio for several years before they were sold, a strategy that left the foundation with an endowment of $1.5 million.

Despite the rapid growth in the size of the foundation, its charitable donations did not increase at the same rate. Johnson's foundation distributes roughly 5 to 10 percent of its value every year, barely enough to meet the minimum standard required to retain its tax-exempt status. In 2014, the foundation gave away no money at all, relying on the larger gifts from years past to keep it in compliance with the law.

"Not only is the Grammie Jean Foundation in complete compliance with the law, it has given hundreds of thousands of dollars to worthy causes, well above all giving requirements, all while being funded quietly by the Johnson family without any personal gain or desire for recognition," Brian Resigner, the communications director for Johnson's re-election campaign, told Salon by email.

As the Washington Post's David Fahrenthold recently explained to NPR's Terry Gross, "a lot of wealthy people have a foundation" and "put their own money into it, so they get the charitable deduction right away." They then make charitable donations directly from the foundation's account.

As Fahrenthold elaborated, numerous "social rituals" among the wealthiest Americans are built around philanthropy. They buy tables at fancy fundraisers or donate money to get their names into the programs at operas and symphonies. This helps build social capital among their fellow rich folks. Private foundations work, Fahrenthold said, as "a bank account filled with a rich person's money, which they then give away."

Giving away your stocks to charity rather than just selling them and keeping the money seems like a nice gesture on paper. But Johnson didn't exactly give the stocks to charity. He gave them to his own family foundation, and that's an important distinction.

A foundation like the Grammie Jean Foundation works basically as a revolving door of social credit. Johnson has parked about $1.5 million in this tax-exempt foundation, where it can accumulate interest. He can then spend that interest money on prestigious charities without reducing the foundation's capital accounts, and while enjoying the tax benefits of its nonprofit status.

The social nature of these kinds of foundations is evident in the kinds of charities to which the Grammie Jean Foundation donated. Here, for instance, is a list from the foundation's 2012 tax return:

Animal welfare programs, Christian ministries, emergency relief programs, children's hospitals and veterans' organizations are well represented. These organizations are no doubt doing honorable work, but only a few of them have a mission to stabilize people living in poverty so they can move towards self-reliance.

Talking up the power of charity is all well and good, but a look at the charitable giving of people like Johnson suggests it is no replacement for government welfare programs. In 2012, the Grammie Jean Foundation gave almost as much money to dogs as it did to people struggling to pull themselves out of poverty.

And, as noted, the foundation gave exponentially more money in 2013 to an opera house in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, than it did to anti-poverty programs.

That's the nature of charitable giving: It's directed not by actual need so much as by the interests and the concerns of the people who write the checks. Maybe they like dogs or opera houses. Maybe dogs and opera houses have more social value in their circles than less glamorous anti-poverty programs.

None of this is to say that the Johnson family foundation is doing anything illegal -- Salon's investigation turned up no evidence of conspicuous wrongdoing -- or that it is unique. A lot of families park money in foundations so they can give away the interest and look generous, without actually reaching too deeply into their own pockets. Johnson's case is largely notable because of the political benefit it offered him, by allowing him to hold his personal wealth in the foundation for years, instead of putting it in private accounts that would have to be included in his Senate disclosure forms.

More importantly, this all shows that Johnson's claim that charity can do what the federal government cannot is flat-out wrong. Rich people doling out a few four-figure checks to whatever causes strike their fancy is not evil or wrong, but it's also not going to solve any social problems. It will not feed the hungry, house the homeless, provide education to young people in underserved communities, find jobs for the unemployed or deliver healthcare to the uninsured. It simply doesn't work that way.

Shares