Last May, in Ohio, 14-year-old Bresha Meadows ran away from home. She told her relatives that she was scared for her life, "because her father was beating her mother and threatening to kill the whole family.” Her mother, she reported, had suffered many injuries at the hands of her father, including broken ribs, punctured blood vessels and black eyes. In July, Bresha allegedly shot her father, killing him. Bresha’s aunt, Sheri Latessa, told Democracy Now that Bresha was acting to protect her mother, telling her “Now, mom, you’re free.”

There’s a name for this kind of violence: it’s called “battered child syndrome” and it usually occurs in response to years of extreme physical or psychological abuse. In fact, studies show that 90 percent of all such violence is committed by children who have suffered abuse at the hands of the parent over a long period of time.

Bresha Meadows’ alleged actions fit the description of battered child syndrome down to the last detail. The parent is killed in a non-confrontational situation, often while sleeping, without a violent struggle. Prosecutors and outsiders, who don’t know about the abuse, interpret these actions as cold, calculating and amoral. But many of these children believe that killing the abusive parent is the only way to end the abuse and free themselves -- and in Bresha’s case, her mother -- from a life of constant fear.

Bresha is currently incarcerated for her actions, held at the Trumbull County Juvenile Detention Center in Ohio. A petition for her release has garnered more than 18,000 signatures. On Oct. 5, Bresha was put on suicide watch by detention center officials. Prosecutors are considering trying her as an adult, and she could face life in prison.

Now a second scenario. In August, in Washington County, Pennsylvania, Kevin Ewing cut off his ankle bracelet and took his wife hostage at gunpoint. Earlier in the summer, Ewing kidnapped, held and tortured his wife for 12 days, branding her with a metal rod, pistol-whipping her, and keeping her bound and tied in a closet. He repeatedly threatened to kill her, and then himself. The second time around, he did it.. Ewing shot his wife three times, and then shot himself -- just as he had warned.

Records show years of abuse, with many instances documented by the police. Tierne Ewing, Kevin's wife, secured a protection-from-abuse order in 2001, which Kevin repeatedly violated. Two criminal cases were filed against him, one of which put him in jail for seven months. Community members, including those in their church community, knew of the abuse and had tried to intervene. One of them told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that the abuse and violence “had been going on her entire adult life.” Just three days before he killed his wife, Ewing was released on a $100,000 bond after spending three days in the Washington County Jail.

What are the laws and policies that make it possible for 47-year-old Kevin Ewing to be released long enough to make good on his threat against his wife, while 15-year-old Bresha Meadows is incarcerated and faces trial as an adult?

Joanne Smith, executive director of Girls for Gender Equity, a New York-based advocacy organization, argues for trauma-informed support for survivors of domestic violence like Bresha Meadows.

In an interview, Smith told Salon that the criminal justice system failed this young woman at multiple points. “The Bresha Meadows case teaches us that the very system set up to support survivors has failed them and is now punishing them for taking actions into their own hands," she said. "The system is reactionary instead of preventive. When Bresha’s grades dropped in school, that was a sure sign that something was wrong. She then ran away from home and reported the abuse but was asked about the abuse in front of the abuser, her father.”

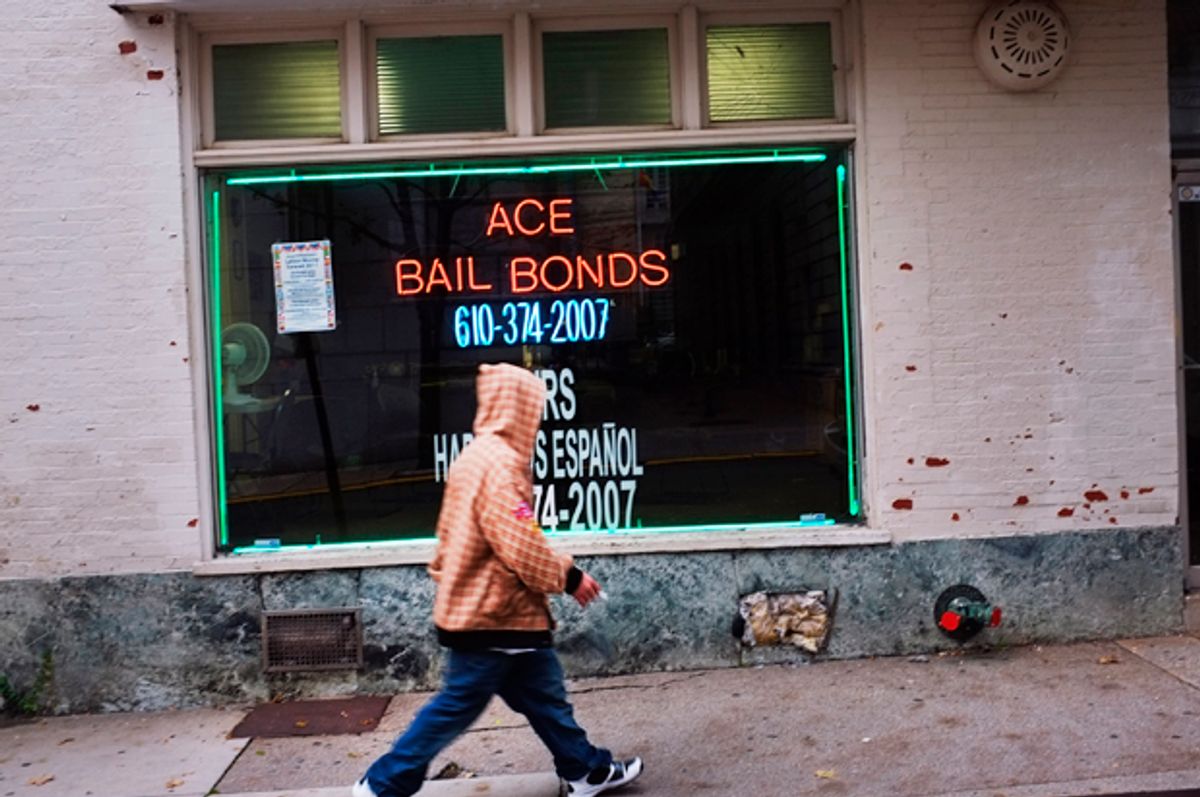

One key element of our criminal justice system is the way in which bail is determined and set. Bail practices are notoriously skewed toward punishing low-income people, who are disproportionately people of color. Cherise Fanno Burdeen, CEO of the Pretrial Justice Institute, notes some of the inherent challenges in a system that doesn’t take into account the risk faced by survivors of domestic violence.

In most places, Burdeen says, the bail-bond system overlooks previous instances of domestic violence. She and her organization advocate for a risk-assessment system in which a person’s risk to others is taken into consideration when setting bail. Victims are not necessarily notified, she says, when an accused abuser is being released from custody. Furthermore, she argues, “The setting of a money bond sometimes poses a false sense of security.”

Advocates like Burdeen are making the case that each arrested person who seeks to post bond should be assessed on the risks they pose to others, and that these risks should be measured by an actuarial risk assessment tool. This process would allow courts to decide whether or not to detain someone before trial. After two years of testing such a risk assessment formula, last year the Laura and John Arnold Foundation introduced its public safety assessment in 30 jurisdictions, including states like Arizona and New Jersey and cities like Chicago and Pittsburgh. This approach is supported by other nonprofit institutions, including the Open Society Foundation, which has has a pre-booking diversion program that promotes alternatives to jail for drug use, and the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, which has focused on changing the way jails are used in 20 key jurisdictions. These changes include strategies to reduce the number of arrested people who are sent to jail and increased use of evidence-based tools such as risk-assessment processes.

One significant question remains unanswered: Will such risk-assessment programs mitigate some of the racial bias, and other kinds of implicit bias, that disproportionately target poor people of color and result in increased incarceration and unfair bail and sentencing policies? Former Attorney General Eric Holder told the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers in 2014 that while information gathered in some risk assessment tools, like education levels, socioeconomic backgrounds and neighborhood, can be useful in some areas of law enforcement, he cautioned against using such data to determine prison sentences. Such assessments, Holder said, “may exacerbate unwarranted and unjust disparities that are already far too common in our criminal justice system and in our society.” Whether this is true for bail-setting policies is a slightly different, but related question.

There is currently a robust debate about the impacts of these programs, and data is coming in from cities, states and municipalities around the country. The fact remains, however, that the criminal justice system as it stands has incarcerated Bresha Meadows and let Kevin Ewing walk out of jail.

Bresha’s case also draws attention to the damage that pretrial detention can cause. As noted in the Department of Justice’s Ferguson Report, some court systems fail to give credit for time served before trial. For a teenager like Bresha, the impact of that could be devastating.

Trina Greene Brown, founder of Parenting for Liberation, expressed concern in an interview that Bresha was "being re-traumatized while incarcerated." If her case stays in juvenile court, Bresha could be remanded to detention until age 21 if she is convicted of murder. "If her case is moved to adult court," Brown said, "she could face life behind bars."

Bresha Meadows' case goes a long way toward illuminating the disparities in the criminal justice system, showing us who is considered innocent until proven guilty and who is criminalized without due process. Brown observes that the system failed Bresha twice. “Bresha’s case reminds us that the criminal justice system is unjust when it comes to black girls. This system was never established to save and protect black girls. It has failed Bresha and many other survivors of color ... who were not provided proper protection, forced to defend themselves, then punished.”

Shares