After successfully pulling off a crucial technical maneuver, the ExoMars spacecraft is now two days away from making history.

The primary objective of the European Space Agency's ExoMars mission is to determine if enough methane and other gases exist on the Martian surface to prove that life exists — or used to — on the Red Planet.

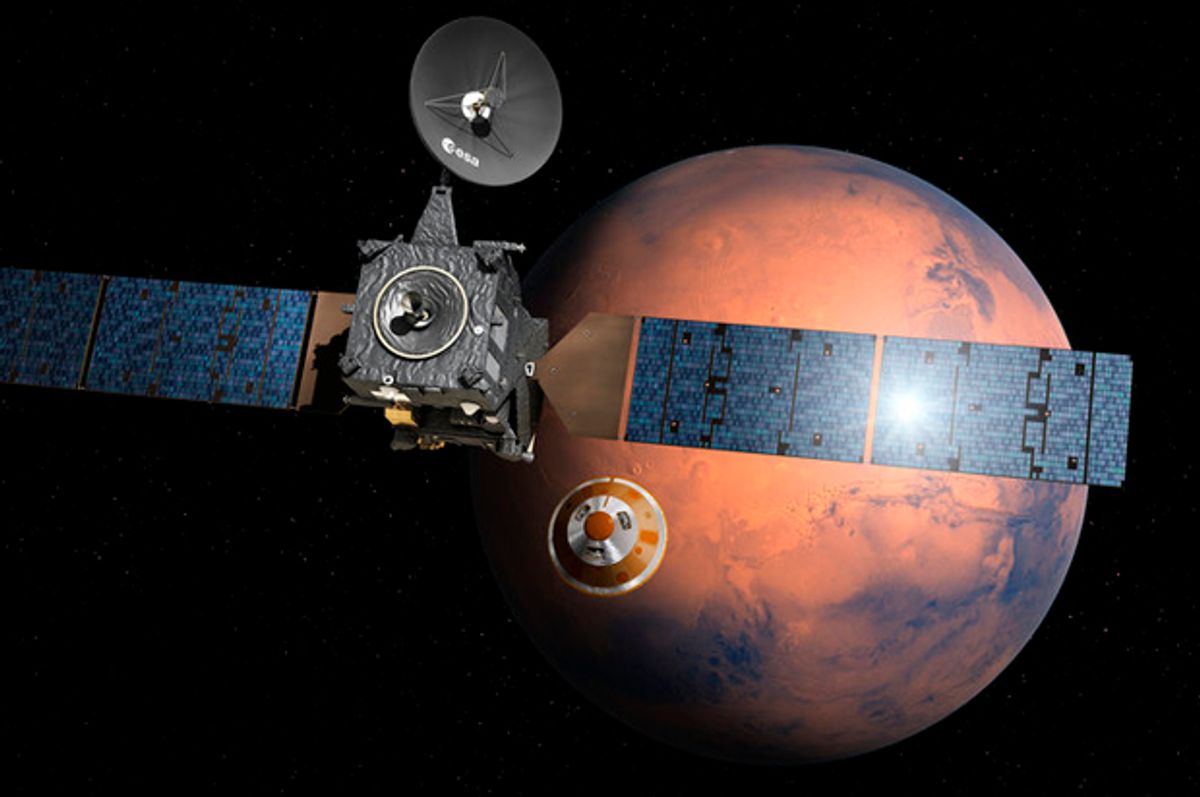

To complete the first phase of the process for doing this, ExoMars needs to release an orbiter known as the Trace Gas Orbiter into the Martian atmosphere and safely deposit a lander called Schiaparelli on the planet’s surface. On Sunday morning, Europe’s and Russia’s two probes successfully separated from each other, a move that was necessary to send each one to their intended destination. If all goes according to plan, both probes will arrive where they need to be on Wednesday.

“We know that there’s methane in the atmosphere, but we’re not sure how it got there,” explained Nicolas Thomas, a member of the team responsible for the orbiter, in an interview with New Scientist. “Methane has a relatively short life in the atmosphere, so the fact that it’s there suggests an active source.”

This is why, when hints of methane were first detected on the planet in 2003, scientists speculated that this could be a sign of extraterrestrial life.

In addition to searching for methane, the Trace Gas Orbiter will also improve maps of the planet and relay signals between Earth and other rovers on Mars' surface. Schiaparelli, on the other hand, will provide data on temperature, humidity, winds and pressure where it lands.

You can track ExoMars’ progress at the European Space Agency's site. It'll be a gas.

Shares