This piece originally appeared on The Conversation. Read the original article.

In what looks very like a tit-for-tat downgrading of bilateral relations, Russia and America have traded diplomatic insults in recent weeks over nuclear weapons, geopolitics and economics, prompting speculation about “a new Cold War”.

Moscow acted first, announcing on October 3 that it had suspended its agreement with Washington on the disposal of surplus weapons-grade plutonium. Russian president, Vladimir Putin, accused the United States of “creating a threat to strategic stability as a result of unfriendly actions towards Russia”. He cited the recent build up of American forces in Eastern Europe, especially the Baltic states.

For its part, the US suspended talks with Russia over the war in Syria, on top of its existing sanctions against Moscow over Russia’s 2014 military actions in Ukraine.

How to escape from this standoff? Are there any lessons to be learned from the era of détente and the end of the Cold War in the 1970s and 1980s? In particular, about the role of international statecraft and personal dialogue between leaders?

Icelandic freeze

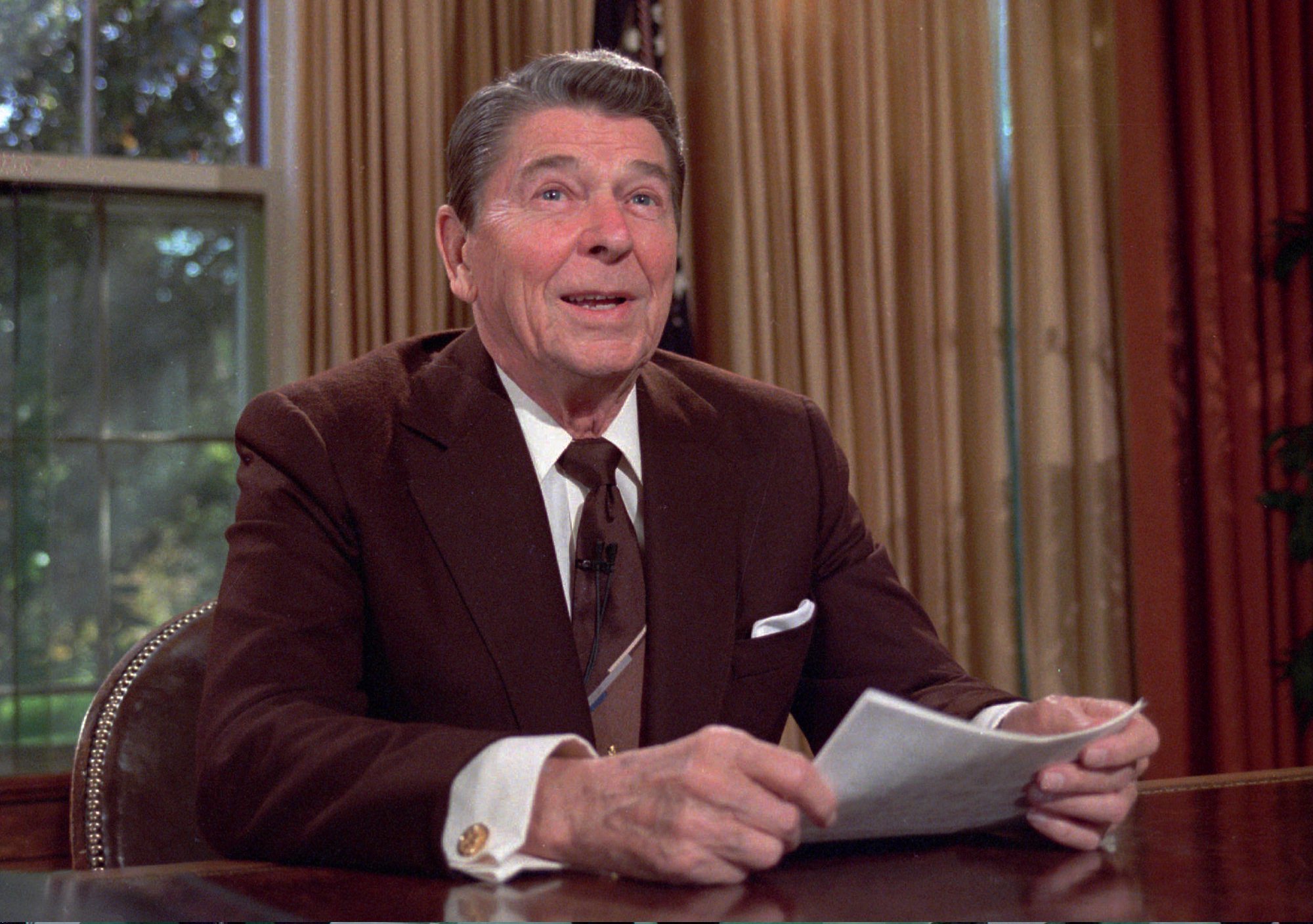

October 2016 marks the 30th anniversary of the summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in Reykjavik, Iceland which had aimed for an agreement on bilateral nuclear arms reductions. At the time the meeting was depicted in the media as a total failure, particularly over Star Wars, the US plan for a sophisticated anti-ballistic missile defence system. “No Deal. Star Wars Sinks the Summit,” Time magazine trumpeted on its cover with a photo of two drained and dejected men, unable to look each other in the eye.

TIME Magazine

The last session ended in total deadlock between the two leaders – maybe a fateful missed opportunity. “I don’t know when we’ll ever have another chance like this,” Reagan lamented. “I don’t either”, replied Gorbachev. They wondered when – or even if – they would meet again.

This familiar, negative narrative was – and is – shortsighted. In reality, both leaders soon came to a more positive view of the summit. Far from being a “failure”, Gorbachev judged Reykjavik to be “a step in a complicated dialogue, in a search for solutions”. Reagan told the American people: “We are closer than ever before to agreements that could lead to a safer world without nuclear weapons.”

Reagan and Gorbachev had both learned how open discussion between those at the top could cut through much of the red tape and political misunderstanding that ties up international relations. At Reykjavik, even though Stars Wars proved a (temporary) stumbling block, both sides agreed that they could and should radically reduce their nuclear arsenals without detriment to national security. And this actually happened, for the first time ever, just a year later when they signed away all their intermediate-range nuclear forces – Soviet SS-20s and US Cruise and Pershing II missiles – in Washington in December 1987.

The treaty testifies to the value of summit meetings that can be part of a process of dialogue that deepens trust on both sides and promotes effective cooperation. Reagan and Gorbachev clicked as human beings at Geneva in 1985, they spoke the unspeakable at Reykjavik in 1986 with talk of a nuclear-free world – and they did the unprecedented in Washington in 1987 by eliminating a whole category of nuclear weapons. All this helped to defuse the Cold War.

It’s good to talk

Today, however, the world seems in turmoil and trust is once again in short supply. We seem to be back to political posturing, megaphone diplomacy and military brinkmanship. Is there is any place for summitry in a situation of near-total alienation? This question was, of course, at the heart of the easing of hostilities in the 1970s, when East and West tried to thaw relations and find ways of living together peacefully.

Helmut Schmidt, West Germany’s “global chancellor” of the 1970s, was a great practitioner of what he called “Dialogpolitik”. He argued that leaders must always try to put themselves in the other person’s shoes in order to understand their perspective on the world, especially at times of tension. He favoured informal summit meetings as a way to exchange views privately and candidly, rather than feeding the insatiable media craving to spill secrets and proclaim achievements.

EPA/Stephane Mahe

In the early 1980s, when superpower relations were stuck in a deep freeze, Schmidt conducted shuttle diplomacy as the self-styled “double-interpreter” between Washington and Moscow. Even when no real deals were in the offing, he believed it particularly vital to keep talking.

The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, recently revived Schmidt’s approach, emphasising the need to maintain lines of communication with the Kremlin at a time of renewed East-West tension. Equally, however, she has insisted on the importance of a strong defence capability. Merkel is surely right. There is always a delicate balance to be struck between the diplomacy of dialogue and the politics of deterrence – making up your mind when to reach out and when to stand firm. Three decades on from Reykjavik, that remains the perennial challenge for those who have the vision, skill and nerve to venture to the summit.

![]()

David Reynolds, Professor of International History, Fellow of Christ’s College, University of Cambridge and Kristina Spohr, Associate Professor of History, London School of Economics and Political Science