I was 10 years old when I sat through my first abstinence series at church. My parents had discussed its age-appropriateness, but had decided that my relative youth was a good thing. It meant my first introduction to sex would come within the safe, godly confines of our church. So I sat in the church sanctuary dutifully every week as various pastors took turns stressing the dangers of things like necking. I didn’t have any idea what necking was, but I made a mental note to avoid it.

Those first lessons in abstinence were downright confusing. I wondered why the French apparently kissed differently than Americans, and why their methods would be so much more provocative and potentially sin-inducing. To a 10-year-old, or at least to a 10-year-old who hadn’t even been allowed to watch kissing scenes in movies, kissing just seemed like slamming your face against someone else’s mouth; I couldn’t imagine there was a whole lot of technique involved.

Once I hit middle school, as others preteens were taking sex ed, beginning to learn about their developing bodies and eventually how to stick a condom on a banana, my mother assigned me to read books with titles like “The Bride Wore White,” “Passion and Purity” and “I Kissed Dating Goodbye.” My home school sex ed curriculum sounded like one of the D.A.R.E. commercials I’d seen while watching Saturday morning cartoons: Just say no.

Even masturbation could lead to your virginity (AKA your worth as a person) being devalued. So when I was much older than I care to admit, I asked my mother: “How do women even have orgasms? How is that possible? What’s happening?” and “Why do people move around so much when they have sex? Can people have sex without all that moving?” Her reply: “You’ll find out when you’re married.” Even learning about my own anatomy was off limits, apparently, until I’d signed my name on a marriage license.

Meanwhile in church, my youth pastor, after pulling a slimy pink glob of bubble gum out of his mouth, asked: “Does anyone want this piece of gum?” The teens all gagged. “That’s what it’s like to marry someone who has already had sex,” he warned.

Other classy youth group metaphors involved comparing teens who’d already cashed in their V-cards to soiled snow, a licked candy bar, a white sheet dropped in mud, duct tape that could no longer stick, and a glass of water a bunch of boys had spit in that no one in their right mind would drink. Eventually, I would learn to recognize this kind of talk as slut-shaming, but at that point I just called it “God’s design for sex.”

Sex outside of marriage was dirty, depraved and sinful. Words like “perversion” were applied to sex out of wedlock. But what was worst of all was the attitude that if you went to bed before you were legally wed you’d become dirty, unwanted, a disgrace. As my youth pastor and the purity books my mother gave me liked to say, “There’s nothing more valuable than a girl’s virginity.” Sex was a dangerous force; it had the life-ruining power to snatch your very worth as a person right out from under your nose.

The message was clear: No Nice Christian Boy would want to marry a girl who had already done the nasty.

Throughout high school I wore a purity ring my mother had bought for me at the local Christian bookstore. I did this partly out of a desire to fit in (everyone else at youth group was doing it) and partly with the hopes that it might scare away any ill-intended men. Losing my virginity was one of my biggest fears, so I wanted to keep anyone who might pose a threat to it at bay.

However, once I graduated from high school all the silver band reading “True love waits” really did was bring up my lack of a sex life in awkward settings with strangers. “Are you married?” a guy would ask. Or, “What does your ring say?” I felt like with that neon I’ve-Never-Had-Sex sign strapped to my hand I was announcing that I was really just a child.

“I’ve decided not to wear my purity ring anymore,” I told my mother one day when I was 18. I’d gone swing dancing and in the course of one night had had two guys ask what my ring said, and I’d had enough. I didn’t want to talk about my lack of a sex life anymore. I didn’t want it on display. I took my ring off and shoved it in a box in my closet.

Mom tried to talk me out of it. “Maybe you could get a different ring if you don’t like that one anymore,” she’d suggested. She was worried. Maybe she feared this marked the beginning of a change. But taking off my purity ring wasn’t the beginning of my sexual revolution.

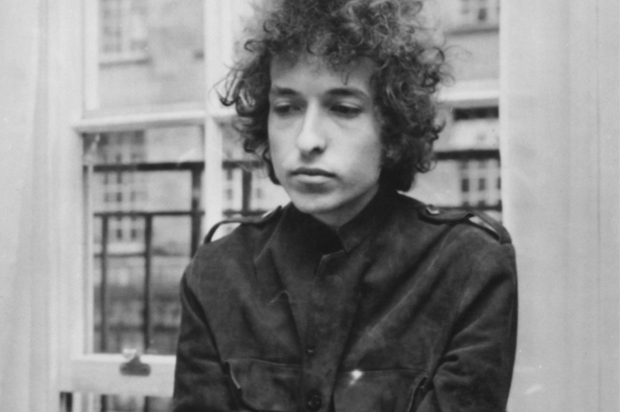

That started with Bob Dylan.

The same year I took off my purity ring I discovered Jack Johnson. But the fact that I’d mostly traded in my Christian praise-pop for “secular music” was no sign that I was now the wild tart I’d been warned against becoming. I mean, I still deleted all of the more blatantly sex-themed songs by Johnson so that they wouldn’t even accidentally show up if I was listening to my music on shuffle.

Jack Johnson was a gateway. I began to investigate more singer-songwriters, working backwards through music history until finally, luckily, I found my way to Bob Dylan. “Lay, Lady Lay” was one of his first Dylan songs I heard, and the sensuality of the song was far from subtle: “Lay, lady lay / lay across my big brass bed.” But I didn’t delete this one. Instead, I hit repeat.

In church and at home, sex outside of marriage had always been chalked up to rampant hormones, a lack of self-control, and lust. “Don’t be friends with non-Christian boys,” my youth pastor had once informed the girls at church. “All they want out of you is sex.” Unless a guy offered a ring and his last name, his desire for you was deplorable. But even if marriage was part of the package, sex wasn’t seen as all that important. “People put too much emphasis on attraction. Just don’t marry anyone who makes you go ‘ew,'” had been my mother’s advice.

One line in particular from “Lay, Lady Lay” I wanted to hear again and again, until it began to echo in my brain: “I long to see you in the morning light / I long to reach for you in the night.” It took my breath away. I’d always imagined a guy expressing his desire to sleep with me sounding more like: “Hey, baby, I want in your pants,” like random strangers rolling down their car windows to call me a bitch or a whore and yell that they wanted to fuck me as I walked down the sidewalk.

But Dylan inviting a woman to come lie down next to him so that he could see her in the morning light wasn’t harassment and it wasn’t crass; it was art.

To my surprise, I realized that if a significant other ever said something similar, I’d be flattered.

I privately continued to listen to Dylan in college, keeping my ear buds in to prevent my mother from hearing. I created a special playlist called “sexy songs.” It was the first time in my life I’d written the word “sexy” and meant it positively.

Every time I listened to “I’ll be Your Baby Tonight” I’d close my eyes, imagining the scene and taking in every word.

Close your eyes, close the door

You don’t have to worry anymore

I’ll be your baby tonight

Shut your eyes, shut the shade

You don’t have to be afraid

I’ll be your baby tonight

One by one Dylan’s songs taught me about sex. While he might not have given me IKEA-style instructions, complete with stick figure illustrations regarding the mechanics of sex or how to properly use a condom or when to apply lube, Dylan taught me the thing I needed to know more than anything else about sex. He showed me sex was something I’d never known it could be before: beautiful.

In “Tangled Up in Blue,” Dylan sings about how a woman opened up a book of poems “And handed it to me / Written by an Italian poet / From the thirteenth century / And every one of them words rang true / And glowed like burnin’ coal / Pourin’ off of every page / Like it was written in my soul.” Every time I replayed my scandalous, secret playlist I felt like every word Dylan sang was being written in my soul, healing the broken parts of me and slowly eroding the negative, shaming things that I’d internalized about my sexuality.

I was 23 when I finally got the chance to see Dylan perform live at Seattle’s Bumbershoot music festival. It was originally going to be a date, but my mother had invited herself along because as she’d put it, “Seeing Dylan is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity!” And I hadn’t had the heart to deprive her of such an opportunity by pushing back.

At one point during the show I leaned against my boyfriend Ian and he slid his arm around my waist, pulling me in closer as we watched what looked like a miniature Bob Dylan performing up on stage. In response, my mother stood up dramatically to go watch the show from somewhere else. She was clearly angry — the dagger eyes were a dead giveaway — and the next day she locked herself in her bedroom for hours to sob about how her daughter had gone astray. “I don’t even want to think about what you’re doing when I’m not around!”

Seeing Dylan live was one of the most romantic moments of my life. After my mother stormed off, Ian wrapped his other arm around me and we swayed together among a sea of humanity and the glare of stage lights. The guy I’d fallen in love with was holding me close as I sang along with every word of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

Eventually Ian would tell me in his own way that he longed to see me in the morning light, to reach for me in the night. And eventually he would. Dylan may have won the Nobel Prize for Literature “for having created new poetic expressions,” but I would give it to him for showing me the beauty in one of the oldest poetic expressions of all.