When, in 1994, the Sistine Chapel reopened to visitors after a decade of restoration, the world drew a collective gasp. Michelangelo's painting, the most famous fresco in the world, looked nothing like it had for the past few centuries. The figures appeared clad in Day-Glo spandex, skin blazed an uproarious pink, and the background shone as if back-lit. Was this some awful mistake, an explosion of colors perhaps engineered by the sponsor, Kodak? Of course not. This was how the work that would launch the Mannerist movement and its passionate followers of Michelangelo's revolutionary painting style originally looked before centuries of dirt, smog, and candle and lantern smoke clogged the ceiling with a skin of dark shadow. This restoration required a reexamination on the part of everyone who had ever written about the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo.

After four years of restoration by the Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels), an equally important work of art was revealed on Oct. 12, and with similarly reverberant consequences. The painting looks gorgeous, with centuries of dirt and varnish peeled away to unclog the electric radiance of the work as it was originally seen, some six centuries ago. But this restoration not only reveals new facts about what has been called “the most influential painting ever made,” but also solves several lasting mysteries about its physical history, for it has also been called “the most coveted masterpiece in history,” and it is certainly the most frequently stolen.

On Oct. 12, I broke the story of the discoveries of the recent restoration of the painting. But there are many more details to tell, some of which have not yet made print.

***

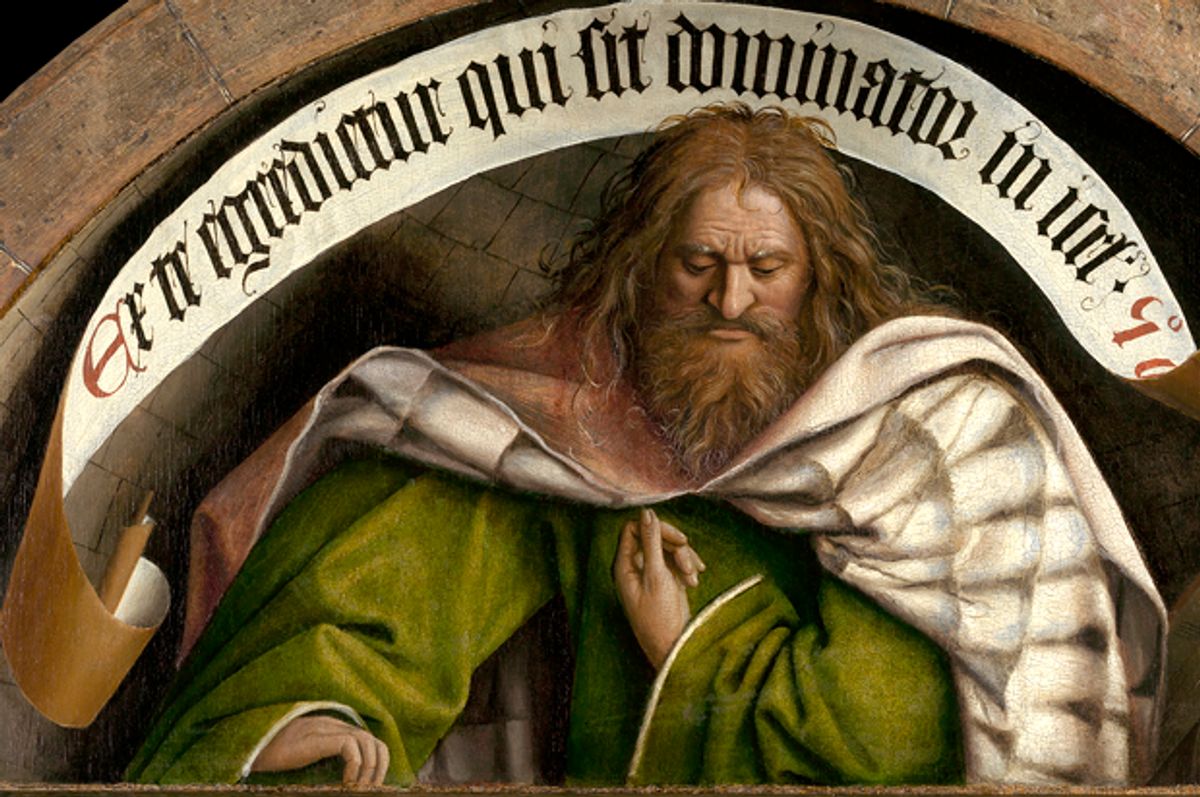

"The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb," often referred to as the Ghent Altarpiece, is an elaborate polyptych consisting of 12 panels painted in oils, which is displayed in the cathedral of St. Bavo in Ghent, Belgium. It was probably begun by Hubert van Eyck around 1426, but he died that year, so early in the painting process that it is unlikely than any of his work is visible. But it was certainly completed by his younger brother, Jan van Eyck, likely in 1432. It is among the most famous artworks in the world, a point of pilgrimage for educated tourists and artists from its completion to today. It is a hugely complex work of Catholic iconography, featuring an Annunciation scene on the exterior wing panels (viewed when the altarpiece is closed, as it would be on all but holidays), as well as portraits of the donors, grisaille (grey-scale) representations of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, and Old Testament prophets and sibyls. These exterior panels on the wings of the altarpiece are what has been restored so far, and what has revealed such rich discoveries.

The complex iconography is something of a pantheon of Catholicism. Adam and Eve represent the start, and Adam’s Original Sin is what required the creation of Christ in the Annunciation, and his ultimate sacrifice is what reversed Original Sin. But the visual puzzle of the painting is just one of its mysteries. For the physical painting itself, and its component panels, have had adventures of their own. The painting, all or in part, was stolen six times, and was the object of some 13 crimes and mysteries, several of which are as yet unsolved. But the discoveries made by conservators have peeled away not just varnish, but the veils on several of those mysteries, as well.

***

After the 2010 study of the painting, it was determined that the altarpiece needed conservation treatment and the removal of several layers of synthetic Keton varnishes, as well as thinning down the older varnishes added by past conservators, while adjusting the colors of older retouches. Bart Devolder, the young, dynamic on-site coordinator of the conservation work, explains, “Once we began the project, and the extent of over-painting became clear, the breadth of the work increased, as a committee of international experts decided that the conservators should peel away later additions and resuscitate, therefore, as much of the original work of van Eyck as possible.”

A 1.3 million EUR grant (80 percent of which came from the Flemish government, with 20 percent from the private sponsor Baillet Latour Fund) and four years later, only one-third of the altarpiece has been restored (the exterior wing panels of the polyptych), but the discoveries found are astonishing, and tell the story of a fraternal love and admiration that is as beautiful as any in history.

Surprise discoveries included silver leaf painted onto the frames themselves, which produce a three-dimensional effect and make the overall painting look very different. The inscription that Jan was “second in art,” and Hubert was the really great one, was proven to have been part of the original painting — almost certainly by Jan’s hand, a humble homage to his late brother. It also found that many different “hands” were involved in the painting.

Computer analysis of the paint, carried out by a team from University of Ghent, clearly demonstrates different hands involved -- just as linguistic analysis programs can spot authorial styles, and so claim that at least five different people “wrote” the Pentateuch of the Old Testament, computers can also differentiate painterly techniques, even subtle ones (one man’s cross-hatching differs enough from another’s from the same studio, just like handwriting differs, even though we’ve all learned cursive). That different “hands” were involved is not a surprise, as van Eyck, like most artists of his time, ran a studio and works “by” him were, in fact, collaborative products of his studio. The outcome of the analysis is just proof of this, but examples of works certain to have been by Hubert are not known, so it is impossible to yet tell whether his paint strokes are visible today, among the several painters whose technique may be found in the altarpiece. If another work could firmly be linked to Hubert’s hand, then it could be compared via this same software to the Ghent Altarpiece to see if it appears. But some mysteries remain for future art detectives to solve.

“Damage was apparent in x-rays of the two painted donor figures” explains Devolder, “and we assumed that, in cleaning away overpainting and varnish layers, they would expose the damaged layer.” It was first thought that the damage had taken place during the initial painting phase — perhaps in Hubert's studio, and Jan then “fixed it” by painting over it, thereby also repairing his brother’s legacy. But it later proved to be a 16th or early 17th century overpaint.

The conventional dating of the painting was likewise confirmed through dendrochronology (the panels in it came from the same tree), likely disproving a recent theory that the work may have been finished many years later than the 1432 date on which most scholars believe. “During the recent conservation campaign, two additional panels, one from the painting of Eve and the one plank from the panel of the hermits, were dendrochronologically tested by KIK-IRPA and shown to have come from the same tree trunk,” Devolder notes. “In an earlier study, a different pair of panels likewise matched.”

It is unlikely that different panels would come from the same tree and remain in van Eyck's studio for a decade before being used in different sections of the same painting, so it is safe to let the current estimation hold, that it was completed in 1432 and installed as a backdrop for the baptism of the son of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy (van Eyck's patron — the painter also acted as godfather to his son). It also suggests that Jan immediately took up the project of his late brother, aware of its importance to his brother’s legacy and to his burgeoning career, rather than setting it aside and only “getting to it” later on.

The biggest discovery is that up to 70 percent of the work was found to contain over-painting, or later painters adding their own touch to the original, whether for restoration or editorial reasons. If, for centuries, scholars have based their interpretation on a careful analysis of every detail, and it now turns out that some of those details were never part of the original conception of the work, then the reading of the work must be reexamined.

The current round of funding (which was already increased once) allowed for a complete exploration and restoration only of the exterior of the wing panels. Yet the one-third that has been fully restored has revealed such a wealth of information, requiring every chapter and article on the painting to be rewritten, that it raises the question of what might be revealed if, in the future, the rest of the work can be similarly explored. While art historians are already primed to rework their van Eyck publications, there may be more discoveries to come.

Shares