The electric guitar — from the Resonator of the 1920s and Charlie Christian's jazz playing in the 1930s, through Les Paul and the heyday of Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page — unfolds in the pages of "Play It Loud." The book, subtitled "An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar," tells its story through both technical developments and the inventors and musicians who made it all happen.

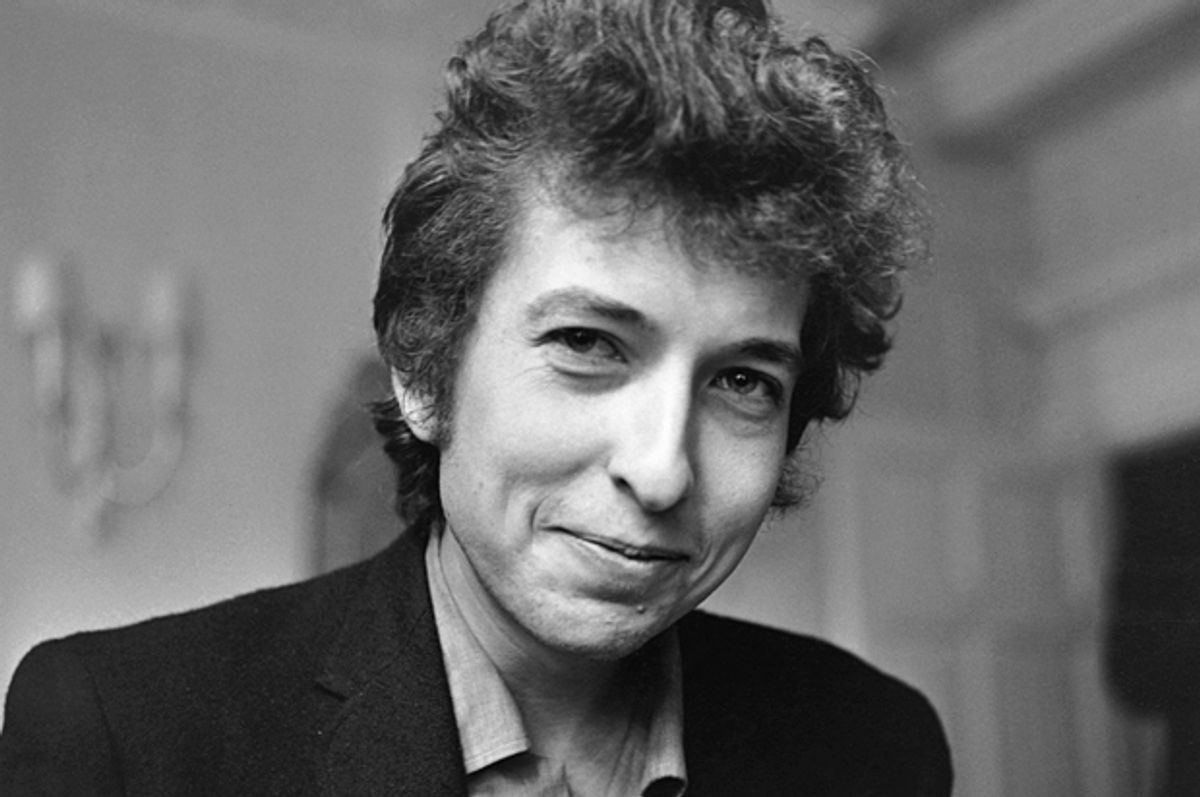

We spoke to one of the authors — longtime Phoenix-based music writer Alan Di Perna — about Bob Dylan's relationship to the instrument. The other author is Brad Tolinski, former editor in chief of Guitar World magazine. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

If we were making a short list of [great] electric guitar players or innovators, Bob Dylan’s name would probably not come up. But he ended up, at the Newport Folk Festival, becoming one of the greatest and most controversial exemplars the instrument has ever had. Can you tell us a bit about his plugging in?

It was Dylan’s third appearance: At the previous two he’d appeared as a bright young folksinger on the scene, a writer of folk songs of social conscience. . . . But by the third appearance, he turned all of that on its ear, appearing with a Fender Stratocaster instead of his folk guitar, and with a fully electrified band, the members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

With Mike Bloomfield as the lead guitarist, I think.

Yeah, and as you say, correctly, Dylan would never make the list of great guitar heroes. But Bloomfield does. He sort of set the archetype for that.

The reason it was so shocking at the time was that the folkies were really committed to the idea of homespun instruments, the voice of the people. It was almost a moral commitment: “We’re only gonna play dulcimers and fiddles.” Rock music represented to them pop crap basically.

And it represented commerce, I guess, instead of that moral commitment to social justice, a counterculture and authentic kind of nonconsumer musical experience.

Exactly. I think it was the folk singer Oscar Brand who said the electric guitar was “a tool of capitalism.” So that’s how they felt. And Dylan was their darling — head and shoulders above even Phil Ochs or Joan Baez . . . . So for him to sell out and go electric was a big deal.

It was like he was saying, “Yes, I am the Pied Piper, I’m pop music, and I’m telling you that this electric guitar is the wave of the future.”

He wasn’t just plugging in; he was doing it in a defiant way.

He was defiant. He knew what he was doing. In fact, as discussed in the book, the Butterfield Blues Band had performed earlier in the festival, with an electric blues set. And the folklorist Alan Lomax was condescending to them, sending the signal, “This is not welcome here.” And Dylan was also championing Butterfield and his guys.

There was an immediate bitter reaction from the folkies and the old left to Dylan’s electrification — rumors of Pete Seeger, I think, taking an ax to the guitar cable or something.

There’s a legend about Seeger. . . . It’s a folkloric festival, so there had been some demonstration of woodchopping or something. And supposedly, according to some of the histories, Seeger said, “If I had an ax, I would have chopped the cable.”

Even before the Nobel, Dylan has been one of the most written-about musicians ever, constantly being assessed in newspaper reviews, books like “Positively Fourth Street” and magazine stories. When we look back at his legacy — the records, the live performances — how much of it has to do with the electric Dylan and how much of it is the acoustic Dylan or the Sinatra-esque Dylan or whatever?

Certainly the records in the canon that are the most revered are the electric records — part of “Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde on Blonde.” It’s so difficult to pick one, but if you had to, “Blonde on Blonde” always makes the charts.

Yeah, an incredible record, nothing like it.

You had Robbie Robertson on guitar on that one.

At the time you almost missed Bloomfield. He had been such a part of “Highway 61.” “Blonde on Blonde” was almost a step toward “Nashville Skyline.”

Right, well, a lot of it was recorded there [in Nashville].

But to answer your question, a lot of [his greatest work] was about evenly divided between electric and acoustic. A lot of the iconic stuff might be Dylan on an acoustic guitar with someone else on electric. But the electric guitar became part and parcel of his palette, his composing process.

Another reason it was significant in ’65 is that adopting the electric guitar came along with a lyric shift. He was moving away from the political stuff, writing this imagistic, adrenaline-fueled, whole new brand of lyric that almost demanded the electrified sound of the electric guitar.

You make a point between the lines of your book that while Dylan was hardly a guitar virtuoso, he was associated with a lot of distinctive electric guitar players, like Bloomfield and Robbie Robertson. Would Roger McGuinn have been a musician in a world without Dylan? McGuinn was an important innovator on the 12-string. Would we have had R.E.M. if the Byrds have not existed? So Dylan and the guitar end up as a pretty important relationship, even if we think of him as a singer and songwriter first.

Yes, and definitely as a guitarist. I’ve spoken to some guitarists who’ve played with him, and they all say he has a very idiosyncratic sense of rhythm, which probably comes from all his years of performing as a solo folkie. Some of the players say that’s a challenge. He’s also famous for starting a song in a different key. So you really have to be on your toes to play with him.

Dylan said Bloomfield was his favorite, of them all.

A few months after the Newport festival, he went on a famous tour of Britain. The concert recorded in Manchester in 1966 was for years one of the greatest-ever bootlegs. Now it’s one of the best official concerts ever recorded. And Dylan’s label is now releasing, what, 36 discs of that first burst of Dylan’s electricity on the road through Britain?

What’s the significance of what we could call the “Judas” tour?

It’s funny: Protesting Dylan’s use of the electric almost became a kind of ritual. It was almost an expected part of the evening.

You were showing your fidelity to traditional folk virtues.

And it quickly became a cliché: On the documentaries about that tour, they’d interview a British fan, expressing displeasure at his use of the electric. It becomes obvious; this fan doesn't get it, can’t move with the times.

There’s also something I write about in the book: There’s this great merging of the youthful rock ’n’ roll audience that had been energized by the British Invasion, by the Beatles and the Animals and the Kinks, joining force with the collegiate, kind of folkie crowd, more serious, more intellectual. They brought a new way of listening to the music: You’re not going to do the Froog at a beach party listening to this. You’ll sit on the sofa, maybe smoke a joint, listen to the words, to what the guitar player’s doing.

So you had all these folk players — Jerry Garcia, Roger McGuinn, Steve Stills, Jorma Kaukonen from the Jefferson Airplane — saying, No. 1: This rock thing is a way to make money. And No. 2: I won’t be disgracing myself.

Right, it offers a serious direction it hadn’t seemed to have before.

And how do you musically assess that British tour, where he is with The Hawks, who would later become The Band, through Britain? Does it seem musically important and impressive? Are you looking forward to hearing more from that tour?

Definitely. You can almost regard it as a baptism by fire. Going out and playing a tour live is traditionally a great way for musicians to get tight together, to bond. But here they are facing boos. They have to win the audience over. They have to play through.

Dylan’s famous “Play it fucking loud!” They had to crank it up to drown out the boos.

I think it’s important — it solidified them as a unit, and it led to "The Basement Tapes."

To ironically, to the kind of rural, rustic Americana Dylan had abandoned at Newport a few years before. It’s amazing how fast things happened for Dylan in those years. My God.

Yeah, it was like going from battle conditions to this kind of pastoral setting.

Shares