When most people think of the Victorian era, they think about the romantic details you see in the movies: the lavish dresses, the ornate furniture, the elaborate and exacting table manners people were expected to adopt. Author Therese Oneill wants readers to look at the other side of Victorian life.

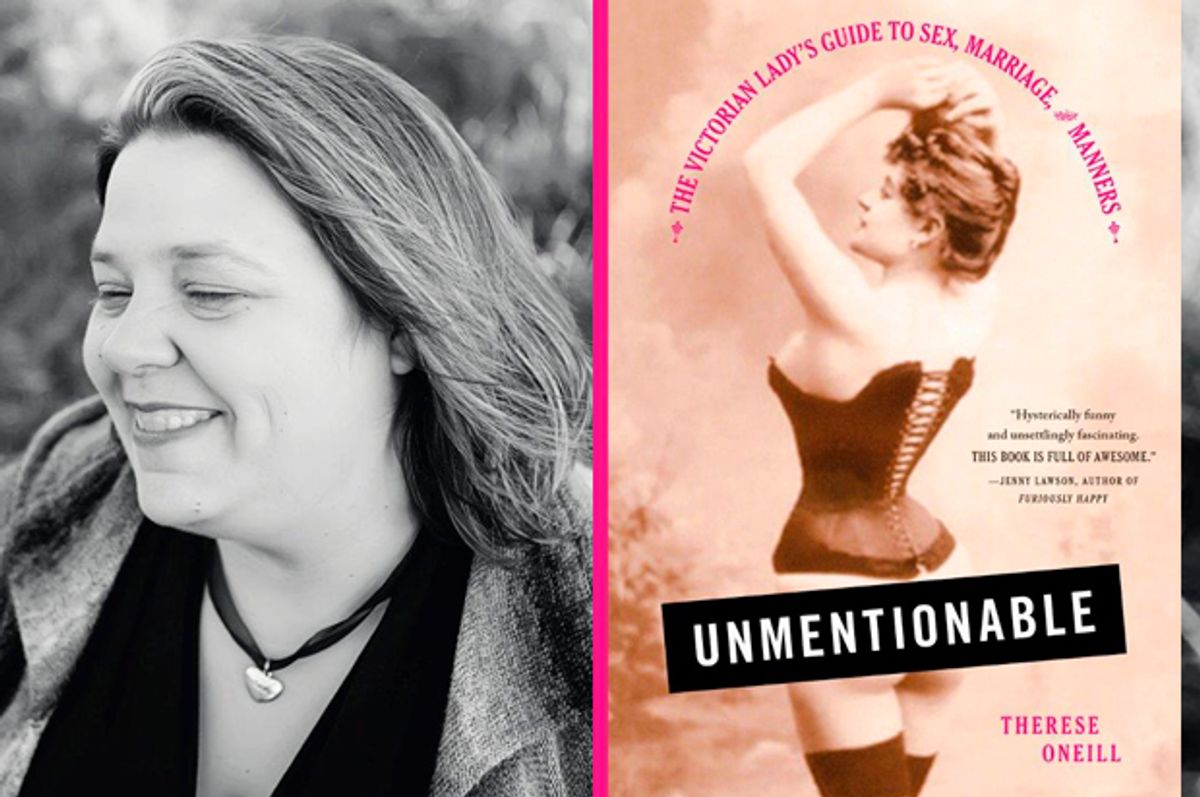

In her new book, "Unmentionable: The Victorian Lady's Guide to Sex, Marriage, and Manners," Oneill digs deep into the aspects of Victorian women's lives that these women would never discuss in public, from how they went to the bathroom to how they were expected to deal with matters in the bedroom.

I spoke with Oneill over the phone about her new book, the historical value of learning about ordinary people's lives and how Victorian women dealt with their periods. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you choose to focus your first book on the lives of Victorian women, especially relatively privileged ones?

The privileged ones are the ones who get the movies made about them and the books about them: Austen, Jane Eyre, the Brontë sisters. They are the ones that women, at least white women, Western women, tend to fantasize that they are. So I figured that was the fantasy that needed the piss taken out of it.

I like to think of it like puzzle pieces missing. You have this great, awesome puzzle, but you get it all done — all 2,000 pieces — except you are missing part of the cat’s fur and the duck’s bill and stuff. And I wanted my job to be digging in the sofa cushions and find the parts that Grandma lost and put them back in and try to fill in those gaps. Because this stuff didn’t get written down much, and it’s part of history and it interconnects everything else together.

It all comes back to vaginas, Amanda.

The first part of your book is gleefully scatalogical. You write about how Victorian women use the bathroom, what kind of underwear they had, their periods, how they took baths. Why did you start in the bathroom, of all places?

Oh, very simple. Because that’s the first thing you do when you get up. I am your tour guide through the day. So, wake up, get dressed, go to the bathroom: Oops, you're on your period. What are you going to do? Then go out and try to get yourself a man. That’s pretty much your job.

There is some available information about how English and American women used the bathroom in the 19th century. But you struggled some to find any information about how women dealt with their periods. Why was that?

That was fascinating. I found scores of information in health and hygiene books written by doctors and sometimes people who just had access to a printing press. And by people, I mean men. Women didn’t seem to write these books — about what your period, blood, color and consistency says about how petulant you are and what personality traits were wrong with you.

I couldn’t find anything about how the actual flow was tended to. And for that, the best source I found was a guy called Harry Finley. He’s like a 78-year-old straight man, single, who runs the Online Museum of Menstruation, or mum.org.

He has the most incredible collection of this unseen information because over the years he had firsthand sources. They send him the actual maxi pad holders that their great-grandma had. They sent him all this real stuff. And I knew it was real because he said, “Well I can’t give you a high resolution of this picture because it is in the garage somewhere.”

So because people sent him so much, he has, in my opinion, the greatest access to this information that nobody wrote down. That’s why we don’t know anything about it. Women didn’t hardly write. What they did, it was private and they just dealt with it. They did everything from handmade maxi pads to grass.

Victorian culture was incredibly prudish in many ways. People, of course, still had sex. How did Victorians reconcile the demand on women to be virginal, to be downright ignorant about sex until their wedding night, and then deal with sex when they were actually married?

Yeah, you’re supposed to toss off your feminine reserve with your petticoats. You have to be the perfect lady in daytime and then become his tawdry little tart at night because otherwise he is going to go find his real tart, and then you are going to get syphilis and it’s going to be terrible.

The only way to get these books [about sex] insides homes, the only way to sell them in the Victorian era was to frame them in the form of hygiene and religion. Like the best-selling book I ever found was called “Search Life on Health.” It doesn’t scream sex, but it is; it is about sex. It is about how to have godly, clean sex. Because people really wanted to know this stuff.

The male writers all counseled to their credit, that you are to remember that even though you technically own your wife — and before the 19th century, you actually did — you have to remember she still is the same nice girl that you courted and married, and you should treat her as such. Unanimously, they counseled to be gentle and patient and even to make sure she is cuddled and loved. I guess their version of foreplay. Not our version because nobody was circumcised and nobody bathed.

But they tried to tell you to be gentle. They said if you start your marriage with a rape, you are going to be miserable for the rest of your life. So they tried.

And they believed a women’s sexuality would spring to life, completely dormant until her legal husband touched her, and then she would be this beautiful, warm Aphrodite who would embrace you and would squeeze out your progeny a few months later and then embrace you again and it would be wonderful. As for what made them think that way — they wanted to.

If you are looking for science, these books weren’t so big on that. At least not the ones that sold.

There were real scientists. They had discovered germ theory back then. They discovered pasteurization back then. But their books didn’t sell. Those books went into medical journals. These books, where the authors, God bless them, pulled most of the stuff out of their asses? They sold.

Women nowadays are frequently blamed for everything that goes wrong with marriage. But in the 19th century, you say, it was even worse. They were blamed for everything from wife beating to a husband’s infidelity. How were women supposed to manage their husband’s behavior when they had very few rights and little power?

A woman's power was her femininity. The "feminine charm" was a very real thing to them. A women who is tidy but not too tidy, a woman who is soft-spoken but not too mousy, a woman who was intelligent but didn’t outshine her husband, was a woman could influence her husband greatly.

She was supposed to gently approach him, make suggestions. Keep her temper, be delicate and use her feminine charm because if he loved her he’d want to please her very much.

That was the ideal. We are talking the Facebook version of Victoriana. It wasn’t like this for the majority of people. This book focused not just on the privilege but the ideal life of the privilege.

Your job is to whimsically charm your husband into doing what you want him to do — like a child basically, like a pretty little girl in pigtails wraps her daddy around her finger. They wanted you to keep that method all the way through your life.

Eventually you are going to turn 50, and your boobs are going to be saggy, and you are going to actually finally know him, after not knowing him when you first got married — because if you courted properly you wouldn’t even know each other. And then he is going to get bored with you because “What happened to the girl I married?” Then he is going to find a newer version, and you need to be graceful about that because it is kind of your fault anyway — getting old and all that, rubbing your wrinkles all over the place.

A woman was considered the queen of her home, queen not king. If you can’t control your home, so that your man has to beat you, that means that you messed up. Whatever you did to make him so unhappy, if you were a true femininely strong, godly wife, it would not have come to that.

The cops don’t care because it is a private affair between you and your husband, unless you can prove he is almost killing you. It just shows you have no control over your home, and you’re supposed to.

In the 19th century, women were often diagnosed with hysteria. What is hysteria and why was it such a common diagnosis?

Hysteria did not exist, not as a real disease. Hysteria was one of two things. It was either a gross misdiagnosis of a real medical condition like diabetic shock or epilepsy or it was the end result of an extremely restrictive society bearing down too hard on a women who was unhappy and bored. It was depression; it was manic depression; it was postpartum depression.

It happened mostly to women of wealth or middle class between the teen years and early 20s, which was when you are kind of bored with life and you still have access to cool stories about love and romance and beautiful things. When you get older, you realize that that is not going to happen for you. And, you know, teenagers go into depression.

They were clueless about this. They really thought the uterus was going crazy.

Dr. [John Harvey] Kellogg cured hysteria by cutting off the clitoris.

Dr. Kellogg married, but biographers think he was celibate his whole life. He ran the biggest and most important health club, the Battle Creek Sanitarium. He had so much power and he wrote so many books. And people flooded to him for advice to make their lives better.

He had an obsession with masturbation and he believed it clogged bowels and would ruin your whole life. It's why he invented corn flakes, to keep your bowels clean and your genitals from being congested.

The story that finally cracked me was that he was brought a 10-year-old rape victim who could not stop touching her genitals, according to her mother. We know now that masturbation is a self-soothing activity for children who have been abused or she could have been grabbing the part of her that hurts.

And he was so determined to save her life, because masturbation would kill her, that he cut her clitoris off. She was a rape victim. And he never followed up. He assumed that it worked because he never heard from her again.

He would blister with carbolic acid the foreskin of little boys. These were children and he believed he was saving their life.

Kellogg had knowledge and power, and he believed he was chosen by God. He didn’t need science. He didn’t need replication, double-blind tests or experiments even. He just needed to chop off the parts that were bothering you. And then squirt a bunch of yogurt up your butt because enemas are really important.

What is the takeaway message you want people to get from this book?

I tease the women who did this stuff in my book, and I tease the people who wrote and told them how to do it — with the exceptions of a few real bite-in-the-asses like Kellogg — because we have no right to be smug because we have a 150 years of science and sociological knowledge on them.

Victorians weren’t evil. They were doing the best with what they had. I want that be clear. We are no better. We've got stiletto heels and chemical peels. It is not that far from putting your face in lead and other God-awful stuff they did.

It is important to know. My great-aunt disagreed with me. She said there are more important things in history than menstruation. But I say, “Like what, bloody wars? Bloody births? It all comes back to vaginas.”

Shares