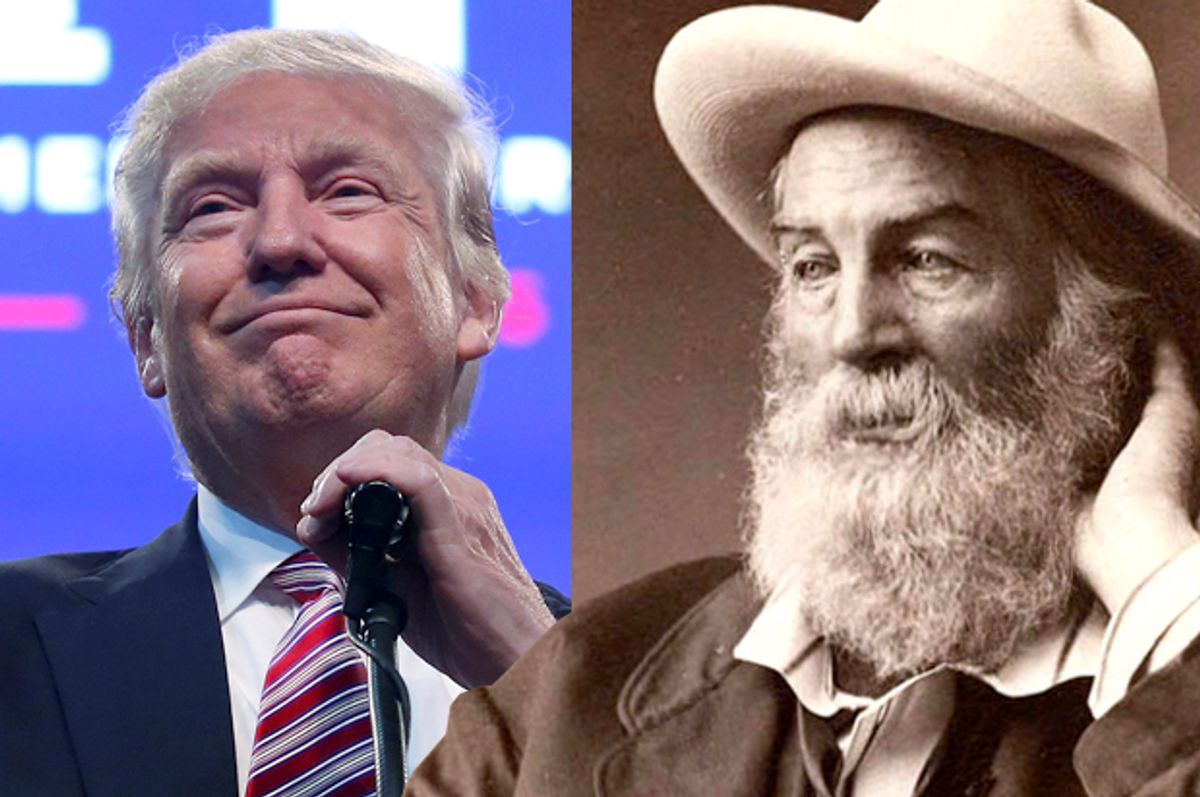

The most wise and visionary analysis of American culture in 2016 and this year's presidential race comes from 1871. In the profound and prescient essay, “Democratic Vistas,” Walt Whitman addressed a nation struggling to unify after the Civil War, and in the turbulence of its democratic struggle, continuing to fail to extend its promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to all its people.

"Leaves of Grass," Whitman’s masterpiece, exercised as inspiration the beauty and brutality of any attempt to turn e pluribus unum into reality. The ongoing altercation to amplify what Whitman, in his poetry, called “the password primeval” and “the sign of democracy” has defined the presidential campaign in ways that would surprise even the sharpest of observers. Whitman believed that the sign of democracy included the voices of slaves, prostitutes, deformed persons, the diseased and despairing, and anyone else whose body gives off the human scent — “an aroma finer than prayer.”

Progress for African-Americans, women, various ethnic minorities, immigrants and LGBT people from 1871 to the present has shaped the story of America, giving emphasis to the possibility of personal and political improvement. With each wave of progressive achievement, there is a backlash. The Donald Trump coalition of angry, afraid and often openly bigoted voters helped to create a development that most pundits call “unpredictable.”

Whitman saw it all coming, much as he would have welcomed the then-unthinkable prospect of a woman president and would have provided healing insight into the difficulty and necessity of performing restorative work to protect and preserve the American experiment of self-governance, inseparable from the unique condition of American diversity.

“I say that democracy can never prove itself beyond cavil,” Whitman wrote in “Democratic Vistas, “until it found and luxuriantly grows its own forms of art, poems, schools, theology, displacing all that exists, or that has been produced anywhere in the past.” Democratic politics demand democratic culture, and without the committed cultivation of that culture, a question will forever haunt the new nation: “The people of our land may all read and write, and may all possess the right to vote — and yet the main things may be entirely lacking?”

Homogeneity is impossible in a country as diverse as America. It now seems that there are elements of American culture lacking the main things — curiosity, avidity, hospitality — while there are other elements failing and failing better as people dedicate their time, thought and labor to building a country of Whitman’s imagination; the “beloved community” of Martin Luther King’s dreams. If that project fails, as Whitman warned, “if America is eligible to downfall and ruin,” it is “eligible within herself, not without.”

One of the most amazing, and frightening, aspects of the candidacy of Donald Trump is how much it despises the American spirit. Trump and his supporters see the rapid diversification of the American public as worthy of hatred, fear and legal opposition. They see the emergence of women in positions of power throughout business, broadcast journalism and politics and react with either juvenile chauvinism or the tacit approval of sexual assault.

The American electoral system, according to Trump and his cultists, is nothing more than a massive conspiracy to undermine the will of the people. The entire country is no longer the source of pride, but in the words of the Republican presidential nominee, a “hellhole.”

The threat of ruin buried within has revealed itself. Whitman understood the dangers of cynicism and how such a mental virus can easily mutate into nihilism, as currently visible with the Trump campaign and its defense of anything in the service of elevating an authoritarian messiah to make American great again. “Never was there more hollowness at heart than at present,” Whitman wrote in 1871. “Genuine belief seems to have left us. The underlying principles of the States are not honestly believed in, nor is humanity itself believed in.”

In place of faith in democracy and human development, Whitman saw a corrosive strain of materialistic reduction to commercial utility in operation as criterion for every judgment. He likened money-making to the “magician’s serpent that ate up all the other serpents.” For all the praise that America deserves for “uplifting the masses out of their sloughs in materialistic development,” Whitman worried that Americans had created a “thoroughly-appointed body with no soul.” A soulless culture, Whitman warned, can easily give rise to manipulative tyrants.

Trump’s entrance onto the political landscape took advantage of the American worship of wealth, and now his vision of American greatness, is that of a body without a soul. The words of Abraham Lincoln imagining and celebrating a government “by, of, and for the people” became the benchmark of political excellence to Whitman, but not without the caveat that a culture of democracy is necessary to make the people fit for self-rule.

“The People are ungrammatical, untidy, and their sins gaunt and ill-bred,” Whitman acknowledged but not without the faith that the “miracle” of original identity, the “luminousness of real vision,” is within everyone’s grasp. The requirements for such an achievement are energy and investment. Democracy, Whitman explained, is “life’s gymnasium. “Freedom’s athletes” come out of the “training school” of political democracy.

Breaking with every imaginable convention in 1871, Whitman wrote that life’s gymnasium would suffer from decay and forever prove inadequate if women remained in secondary roles. It was not only important for women to gain equality with men but also to emerge as leaders alongside men. He wrote of women who defied the stereotypes of subordinate to male authority and called even then for “something more revolutionary.”

Whitman wrote, “The day when the deep questions of woman’s entrance amid the arenas of practical life, politics, and suffrage will not only be argued all around us, but may be put to decision, and real experiment.”

Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton is poised to take the presidency and enhance the experiment of women in leadership at the highest level, as many women mayors, governors, senators, CEOs, professors, doctors and mothers demonstrate strength and wisdom. Trump — and the chauvinism that he represents — displays belief in nothing, fear of competition and the untidy sin of vulgar reduction of humanity to category.

Enriching the democracy of America, and overcoming the nihilism that threatens it, necessitates what Ed Folsom, a Whitman scholar, calls “urban affection.” How do you respect and even have affection for strangers walking past you on city sidewalks? How does democracy begin, in Whitman’s words, to “freely branch and blossom in every individual?”

The choice between a candidate who can make a healthy contribution to that process and another who can only degrade it is almost too obvious for description. More important is the cultural life that will evolve or devolve after the next president takes the oath of office. Whitman did not seek hope in, what he called, “half-brained nominees, ignorant failures, and elected blatherers.” Instead, he found fortification for his faith in the arts and his belief that the arts could help create the culture of democracy so vital to the full exercise of political democracy.

Good art and good literature share certain features, Whitman argued, and it was these features that would prove most useful in the steady realization of the promise of the United States as a country and united states within each person. In "Leaves of Grass," Whitman declared that he was the poet of the body and the soul. The temptation to compartmentalize is part of the disease infecting both the pursuit of happiness within each life and within the national life.

There are “invisible roots” connecting all experience, all spirits and forms, and Whitman advocated for the exploration of these roots. “To absorb and again effuse it, uttering words and products as from its midst, and carrying it into highest regions, is the work, or a main of the work, any country’s true author, poet, historian, lecturer, and perhaps even priest and philosopher,” he wrote.

Art that accomplished the discovery and description of our invisible roots is what has the power to strengthen and unite Americans. The critical inquiry then becomes one of cultural agenda. Is America building an infrastructure for artists, historians and even priests and philosophers to find the invisible roots of our citizenship and humanity? If not, future incarnations of Donald Trump – perhaps more politically savvy and less given to self-sabotage — will soon gain control.

There are two hindsight perspectives on Whitman’s prescience in 1871. One is to consider how many problems still persist and adopt a cynicism that leads only to paralysis. The “nothing will ever change” attitude not only ignores history but also shapes history. One can only imagine if the contributors to movements for civil rights, women’s rights and LGBT rights withdrew from American culture and politics because they thought all improvements were out of the question.

The other is to not fixate solely on the distance left to climb but to look back and take scale of the walls already mounted. The Whitman vision of equality and unity through diversity and individuality seems utopian, but it is important to consider how many voices have already found amplification in the “sign of democracy” that were once muted. As simple as it seems to say, things are getting better and they have been for a long time.

In "Leaves of Grass," Whitman wrote, “Logic and sermons never convince/ The damp of the night drives deeper into my soul.” There is an important election on Nov. 8, and all responsible citizens should vote. It is just an election, though. Then we have the rest of our lives.

The true power of Whitman’s imaginative and inspired hope for America is that it is a rest-of-our-lives hope. How do we want the American night to drive into our souls? Will we feel an elevation of the spirit or further dejection?

The president makes a lasting contribution to the American night, but so does each citizen, and there exists a collective responsibility to construct the culture and cultivate the arts that will make that night starlit, beautiful and sensual, rather than dark, arid and frightening.

Shares