It’s been the best of times, as well as the worst of times: For black Americans, the years since Martin Luther King’s leadership of the civil rights movement have been some of the most triumphant, as well as some of the most frustrating and tragic. Encompassing the integration of restaurants and schools, urban riots and police violence, James Brown and Ronald Reagan’s race-baiting, it’s been a confusing ride.

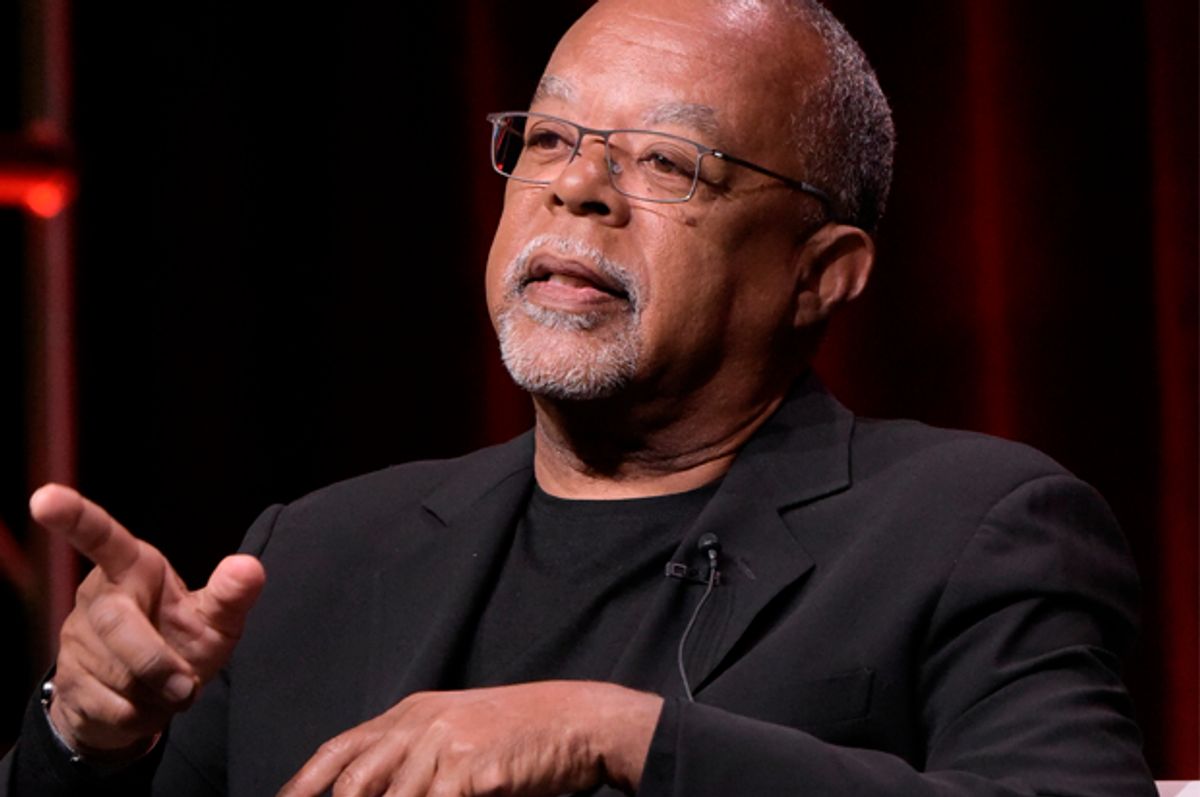

A new PBS documentary, “And Still I Rise: Black America Since MLK,” looks at the last half century through old footage, talking heads and the narration of Harvard scholar and historian Henry Louis Gates. The first two parts air on Tuesday night and on Nov. 22.

Salon spoke to Gates who was at his home outside Boston; the interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

We’re talking the morning after the startling election of Donald Trump and about a documentary dedicated to the last 50 or so years of black American life. Do these subject overlap in any interesting way?

Last night I realized I felt like Frederick Douglass must have felt in 1876 after the [Rutherford] Hayes-[Samuel] Tilden compromise ended Reconstruction. Because this election ended the second Reconstruction.

Right, right. . . . That’s, ah . . .

Think of the civil rights movement to the present as a second Reconstruction — a 50-year Reconstruction — that ended last night.

It was a longer Reconstruction. . . . But that election clearly represented a backlash against the progress black people have made since 1965 — epitomized, symbolically, by the election and term of a black man in the White House. I have absolutely no doubt that this election reflected both anxiety and resentment — and an enormous amount of fear and insecurity. And the two things are tied together: There’s an enormous amount of economic anxiety, that’s understandable, that working people feel. But it got transformed figuratively into xenophobia — anxiety about immigrants, people of color and the ultimate symbol: a black man in the White House.

I also think, that said, that should we not demonize people who are afraid. You’ve been afraid. I’ve been afraid. It doesn’t help if you mock someone who’s afraid. What we failed to do was to understand that anxiety and speak to it. And you have to treat the cause of the illness, not just its symptoms. And its cause is economic.

That is the consistent lesson of race in American history. Racism — like anti-Semitism — its roots were in economic relationships. It used to be if you worked hard, delayed gratification, kept your nose clean, your kid would do better than you did. You moved from basically no class to working class to middle class.

And then people look around to what’s happened to black life since 1965 — the black middle class has doubled, the black upper-middle class has quadrupled. And then it’s “How did they get all that power, if I don't have any power?” And that is the cause of the problem.”

And then Trump said, “I can cure this.” He didn’t have a plan, but he said he did.

“Only I know how to fix it,” I think he said.

“Only I know how to fix it!”

And Bernie did a better job at engaging with economic anxiety than Hillary Clinton. This stuff didn’t much seem to interest her.

I know Hillary Clinton. I know she's passionate about those issues. But somehow her candidacy was not identified with addressing those issues or solving those problems. And it’s a tragedy because she would have been one of the greatest presidents — I can’t believe we’re having this conversation! — one of the greatest presidents in the history of the republic. I think she would have been more effective in the White House than Barack Obama was. And unfortunately, that’s not gonna happen.

We’re developing several new history projects for PBS: One of them is on the first Reconstruction. It’s called “Reconstruction, Redemption and the Birth of Jim Crow.” And it will be a model of what’s going on now.

We'll let’s talk about your documentary for a minute. The key line — I think you use it twice — is “How did we come so far, yet have so far to go?”

And guess what, Scott: We have farther to go now than we did yesterday. The irony of this series is that its timeliness couldn’t be more urgent. We had no idea!

This starts while King is still alive and giving speeches and leading triumphant marches and so on. You were a teenager at that point, I think.

Right, I was 15 during 1965.

So for you — this black West Virginia teenager who surely admired King and his lieutenants — what would have most surprised you about the ensuing decades?

Two things would have surprised me the most. One is the remarkable amount of progress black people have made. The other is the absolute lack of progress so many black people have made.

No one could imagine the extent of the prison population. No one could have predicted that something like 70 percent of black births would be out of wedlock. No one would expect that the child poverty rate would basically stay constant. No one would predict that inequality within the African-American community — the Gini coefficient — would be higher than for white people or Hispanic people.

What happened? It's almost like the door opened and some people were allowed to rush through — who are black — and then it slammed shut. And these two classes of people, [the black elite and the black underclass,] are self-perpetuating, without dramatic intervention by the federal government or private industry. And the possibility that the federal government is going to intervene just ended last night at about 2 a.m., you know? That ship has sailed.

So I think the most dramatic thing about the airing of this series is that it will be a reminder for African-American people, who are successful, of our responsibility more than ever to join hands with the black poor — and say, “We have to fight for the economic mobility of the poor people in the country, particularly African-Americans and we have to use our power and our success.” And particularly now, in a time of crisis. Because the programs that led to our success are likely about to disappear.

So it is a wake-up call to the African-American middle and upper class to join the community of our ethnic group, across class lines.

But it’s interesting. All of the dire things you’ve mentioned have happened or failed to improve. But at the same time, as your documentary makes clear, we've also had a black president — who’s, at times, been pretty popular. The de facto music of people in the States whatever their race is hip-hop or R&B; Kanye and Beyoncé are huge, huge stars. In the visual art world you have people like Kehinde Wiley, and Basquiat is a hero. . . . Not even to get into sports, which have been dominated by black people for a long time. Paul Beatty just became the first American to win a Man Booker Prize. And so on.

So going back to your teenage years, there’s been this huge flowering, embraced by mainstream audiences and institutions. The New York Times cultural coverage. Jazz at Lincoln Center. . . . We’re in a weird, complex, contradictory state.

It’s unparalleled. You’re exactly right. Another way to put it: The lingua franca of American popular culture is African-American, without a doubt. But at the same time, look at the vote. White working-class people elected Donald Trump to be president of the United States, even though there was no logical reason for them to do that. And it’s astonishing, really.

History helps us to understand it. Traditionally, when white working-class people have felt economic anxieties; they have been consistently manipulated over centuries to blame black people for their problems rather than the system itself.

You see that very consistently in your documentary: We go from Martin Luther King and his speeches and the sense of unity, to angry white folks and burning cities. . . . And then all of this enthusiasm about black popular culture and then white flight and the battle over school desegregation.

In Boston!

Yeah, with really scary footage of angry white people in South Boston. Seems like there are these waves of progress and then this backlash — or what we are now calling a “whitelash.”

Yeah, absolutely. And it’s because people think the pie is shrinking. So as soon as black people come to the table they say, “Nah, not enough food here.” I’m not sure this is the right metaphor, but whenever there is a question of the distribution of resources, someone needs to get scapegoated. And in this case, black people.

And specifically, Barack Obama. His 54 percent approval rating was completely undermined by the result of the election. Hillary hitched her wagon to him; she clearly identified herself with Obama. But it didn’t work. There was a shocking amount of resentment that a black family had been in the White House for two terms.

I think it would be naive to overlook it — the irony that one of the legacies of Obama’s presidency was an enormous amount of resentment. And not his fault at all. I don’t think a Donald Trump could have emerged without a black president. Donald Trump tapped into and fueled and stoked an enormous amount of racial resentment. And Obama symbolized it.

I agree with that. But I also wonder if this country would have elected a black president — especially one as young as him, with the middle name “Hussein” — if there hadn't been a crushing economic collapse that his opponent seemed totally incapable of dealing with?

No, absolutely. And he doesn't get credit for his genius in speaking to and dealing with that economic crisis.

There’s a lot of stuff in the documentary I expected to see — footage of “Soul Train,” interviews with Jesse Jackson — but you also have some things like that interview with John Jackson of Alabama, who’s not famous, not exactly a hero of the civil rights movement. But he was there, made good decisions; I think he let Stokely Carmichael and crew stay in his parents’ house.

Yeah, [Jackson] went home and said, “Hey Daddy” . . . . And I said, “Did your parents go crazy?”

Pretty gutsy thing to do. I just wonder: This is a side of the story we don’t typically get when we get the roll call of great names. What do you think people like this did for your film? And maybe for our understudying of black history in general?

Well, I wanted a different way to tell the story of black history. We’re all familiar with the leadership — especially the male leadership, so I wanted to tell the story of Ella Baker. But I was also finding foot soldiers, who didn’t make the evening news but were sitting in those churches, clapping their hands, but had never been interviewed before. So we spent a lot of time on the ground, just talking to people. “Hey, were you there? Do you want to be in the series?”

More of a social history. Like the young black woman who integrated the high school in Boston. We wanted to widen the lens. And they were great! And fresh. It wasn’t like getting Andy Young to give his 5,000th interview on what Martin Luther King was like.

So let’s close with the election. We now, not only have the departure of a two-term black president but the arrival of a guy whose political career started with the “birther" campaign, who's been accused of keeping black people away from his father’s apartment complexes. . . . To the extent that we can generalize, what does a Trump presidency seem to mean for black Americans?

Two things: I think first of all that black people are going to be ever more vigilant and unified and more conscious of each other’s welfare, which is one of the points of the series. And remember — Donald Trump was thought to be a middle-of-the-road liberal —

Yeah, and a Democrat a bunch of times —

Yeah, until Barack Obama was elected and he went crazy over the “birther" issue. I have a couple friends who know Donald Trump, and they say he is nothing, in person, in reality, like the persona he projected during his campaign.

And they’re black people who supported him. [Laughs.] And I hope they’re right. I hope he listens to his black advisers and people like Armstrong Williams and my old classmate Ben Carson, with whom I have major political disagreements. But they are very devoted to Donald Trump. And these are people whose integrity I respect.

Well, Williams is a Christian conservative, I think. He’s not on my side of the fence, but he’s credible. Carson we’ll have to talk about another time.

Neither of these people are on my side of the fence. But at this point we’re desperate that they make their man do the right thing. I hope Donald Trump’s few black supporters, like Williams and like Ben Carson, can hold him to some degree of accountability. And that the words he mouthed about helping the black community at the end of his campaign. . . . We can all only join hands, bow our heads and pray they will come true. But you gotta show me.

Shares