Here we are, repeating history. Since we obviously didn't learn from the past, it's time for Americans to take a refresher course.

Tonight at 8 p.m., PBS member stations air the first two installments of Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s “Black America Since MLK: And Still I Rise,” a four-part documentary series produced during one of the most contentious and divisive presidential election campaigns in our nation’s history.

Journalists and analysts are frantically examining the whys and how of what led to the election of Donald Trump and the rise of white nationalism. A person can and should read those articles, but a more expedient explanation can be found in the “Black America Since MLK,” which shows that what's happening now is part of a recurring theme in American history, particularly over the past five decades.

The economy and the mood of the white working class have long served as accurate indicators about which way the political winds are blowing, as well as where incoming storms are poised to strike.

This is not to imply that Gates expected the ultimate outcome but, if you watch the series, it’s a safe bet that he wasn’t completely surprised.

As Gates told Salon’s Scott Timberg in a recent interview, the election of Donald Trump represents “a backlash against the progress that black people have made since 1965 — epitomized, symbolically, by the election and term of a black man in the White House.” But it also represents a repudiation of the idea that Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of racial equality had been realized by the time Barack Obama took office.

When the economy falters and the wealth gap widens, when white working-class families feel that they’re being left behind and when minorities — and African-Americans in particular — are making visible strides in terms of gaining wealth and influence, the conditions are ripe for what CNN contributor Van Jones has termed a whitelash.

Into this environment comes specific messaging such as “Let’s Make America Great Again” which, as a reminder, was first used in 1980 as Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign slogan. Reagan took office and ushered in an era that included the rise of the drug war and a demonization of the nation’s poor, with black Americans becoming the symbols for those ills.

“’We are taking our country back.’ ‘We’re making it great again,’” says Cornel West in the series. “Anytime white elites [are] talking about taking their country back, [black people] know what they mean. They coming at us with intensity.”

Gates calls the progress achieved during the 50-year period since 1965 a “second Reconstruction,” and that time span is examined in detail in “Black America Since MLK,” beginning with the signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Remember: This pivotal piece of legislation was neutered in 2013 when the Supreme Court deemed a key provision of it unconstitutional, making the 2016 presidential election the first one undertaken without the full coverage afforded by that act.

Watching “Black America Since MLK” certainly helps put our current state of events in context. It’s also as much a celebration of the achievements African-Americans have made over the last half century as it is a sobering reminder of how far black folks still have to go, illustrated through interviews with political figures, civil rights luminaries, scholars and celebrities. The usual suspects weigh in here, including Oprah Winfrey, West, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton and Bell Hooks.

But Gates also interviews people like Kathleen Cleaver, who married Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, and discusses the Black Panthers and their impact on culture, along with other people who lived inside and through historical flash points. One of them, Phyllis D. Ellison, was part of a group of black students bused in 1974 from Roxbury to integrate South Boston High; she and the other children were met on their first day of school by white mobs threatening violence and had to fight for their safety in school hallways and bathrooms every day afterward. The resilience she displays while recalling those frightening memories is awe-inspiring.

Whereas the first hour, “Out of the Shadows,” examines the successes won by King and the evolution of the civil rights movement into a period of political empowerment, the second hour, “Move on Up,” incorporates familiar faces of black success as filtered through popular culture.

This examination of the mainstreaming of black culture in the television, music and film industries continues in the series’ third hour, “Keep Your Head Up,” which premieres Nov. 22 at 8 p.m. The final hour of “Black America Since MLK” was not made available for review, but it might be the most relevant to viewers because it covers more recent history — the span of time between Hurricane Katrina and Obama’s political ascendance to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The pop culture portions of the miniseries may be the most enticing element of “Black America Since MLK” because these contain the African-American faces with which mainstream America is most familiar. Footage from “Soul Train” and archived film of interviews with James Brown and Muhammad Ali are illuminating while also stoking warm nostalgia.

This also is true of segments referencing the level of black success and self-determination reflected in “The Jeffersons ” and “The Cosby Show” via the Huxtable family. Michael Jordan, Michael Jackson, Prince, Dr. Dre, Beyoncé and, yes, O.J. Simpson are some of the celebrities highlighted in the series as evidence of black progress and the entrance of African-Americans into a new stratosphere of stardom and wealth.

But they’re also part of the mythmaking surrounding America’s perception of economic and social parity. For as often as the series points out that African-Americans have enjoyed periods of upward mobility in every decade since the civil rights era, it also dives into the factors conspiring to make black working poor people into what Gates calls a permanent underclass.

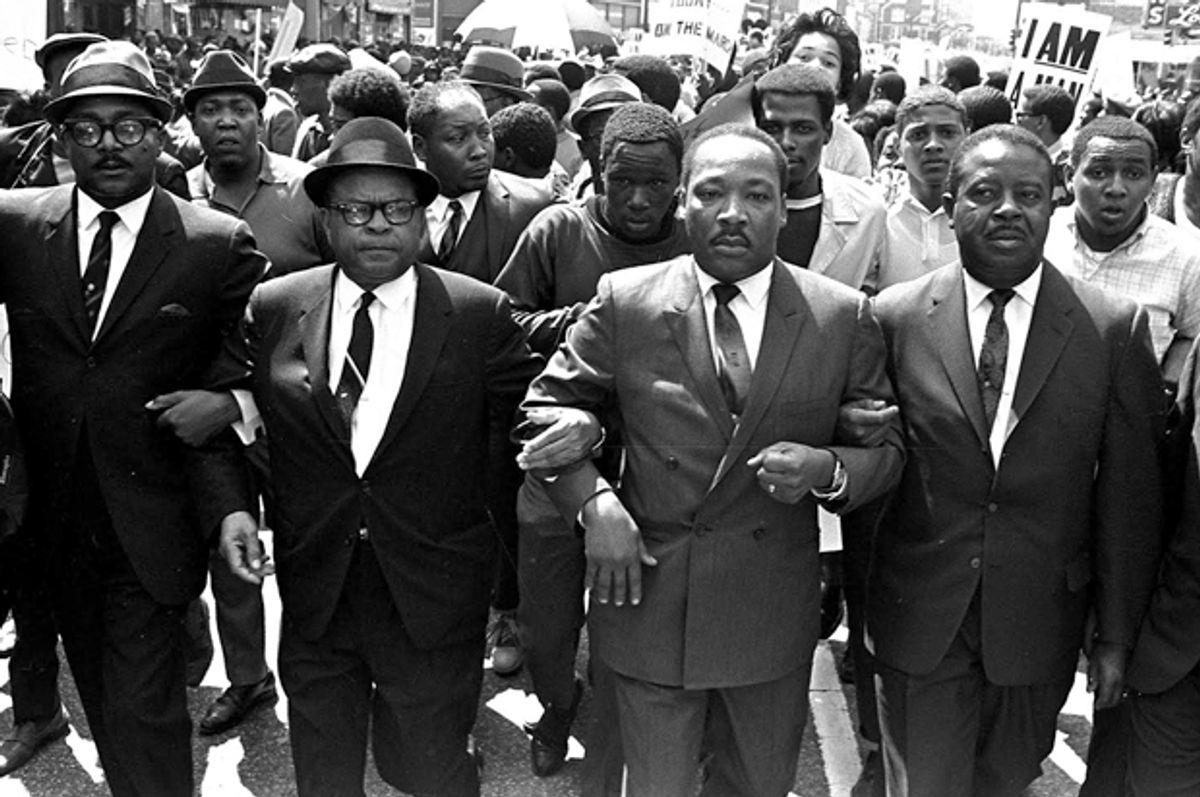

The popularly held idea of King’s dream, the element of his life that exists most prominently in America’s collective memory, represents a dilution of what the man ultimately stood for. By the end of his life, the larger civil rights movement had deemed his nonviolent positions irrelevant, and King pivoted from a primary platform of racial reconciliation toward one that addressed America’s economic imbalance. That’s why he was in Memphis in April 1968 in the first place, to support a sanitation strike.

All Americans, regardless of race or socioeconomic status, can benefit from watching “Black America Since MLK,” if only to be reminded that no justice movement has succeeded without the political and social co-signature of the dominant culture. That was true then, and it remains true now.

As such “Black America Since MLK” provides both a history lesson and a map to understanding that we’ve been on this precipice before. There’s comfort to be had in that knowledge: We as a nation have lived through uncertain times in the past and endured.

We’ve also witnessed what can happen when a civil rights movement becomes fractured and marginalized due to a disconnect between words and their intent. Many of the misplaced fears surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement echo modern statements of distrust surrounding the black power movement. And just as some African Americans chafed at the idea of “Black Power” in the ‘60s and ‘70s, there are those who shy away from today’s civil rights efforts.

But the question that “Black America Since MLK” left me asking is how America will overcome this next cycle. In the 1960s, white Americans were motivated to stand against segregation in reaction to violent images on the evening news featuring protestors being brutalized by police.

Today's TV coverage of protests since the ones that erupted in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 over police shootings of unarmed black people rarely is contextualized with meaningful reporting on the conditions that ignited them. Instead, there’s a growing tendency within the media to downplay or even dismiss their significance, following the lead of a president-elect who blames their existence on the media itself.

All those marches in the street taking place all those decades ago — all that talk about how we’d reached a new day of racial harmony, integration and equal opportunity. And yet, here we are, again.

At one point Gates asks, “How did we come so far and yet have so far to go?” “Black America Since MLK: And Still I Rise” does a tremendous job of answering that question while implicitly leaving us to ask how many of those gains we stand to lose.

One of King’s quotes featured in the series is at once depressing and emboldening. Depressing, because it was delivered on the steps of the state capitol of Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965, at the end of the Selma-to-Montgomery march. The words still apply today, 51 years later — a sad thought. Emboldening, too, because so many are depending on his declaration to eventually be true.

How long, King asked then, “will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?”

“How long? Not long,” he concluded, “because no lie can live forever.”

Shares